The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A History of the Medical Book

Posted on Wed., Nov. 7, 2018 by

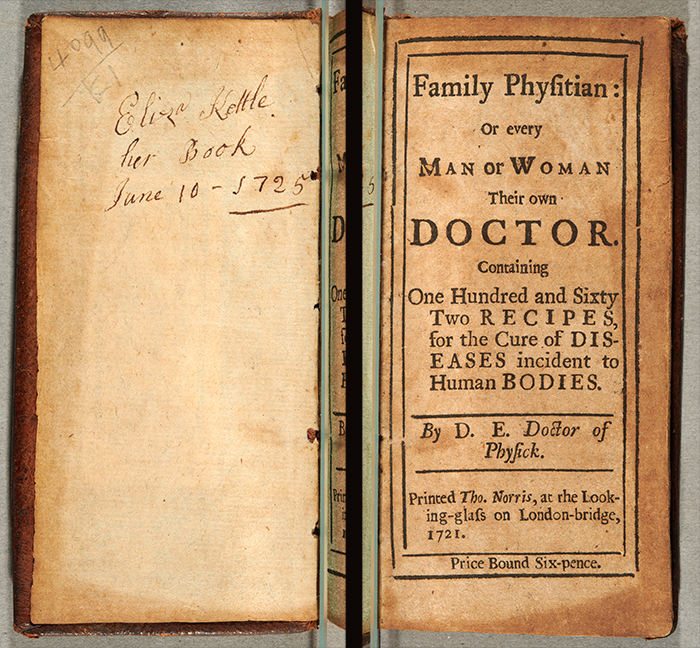

An 18th-century reader inscribed her name in a copy of a small manual about domestic medicine titled Family Physitian: or every man or woman their own doctor, by D.E. Doctor of physic . . . [London]: Tho Norris, 1721.The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When we analyze an early-modern medical book nowadays, we often read it on Early English Books Online (EEBO), Google Books, or a similar platform. While such digitization has opened up all kinds of scholarly opportunities, it has also meant that we less frequently encounter a historical medical book as a material object. I’m convening a conference called “The History of the Medical Book” from Nov. 16–17 at The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall to prompt us to think about the medical books that we study as material objects—in other words, to bring together the history of medicine and the history of the book. I want to ask what the medium might tell us about the message and vice-versa.

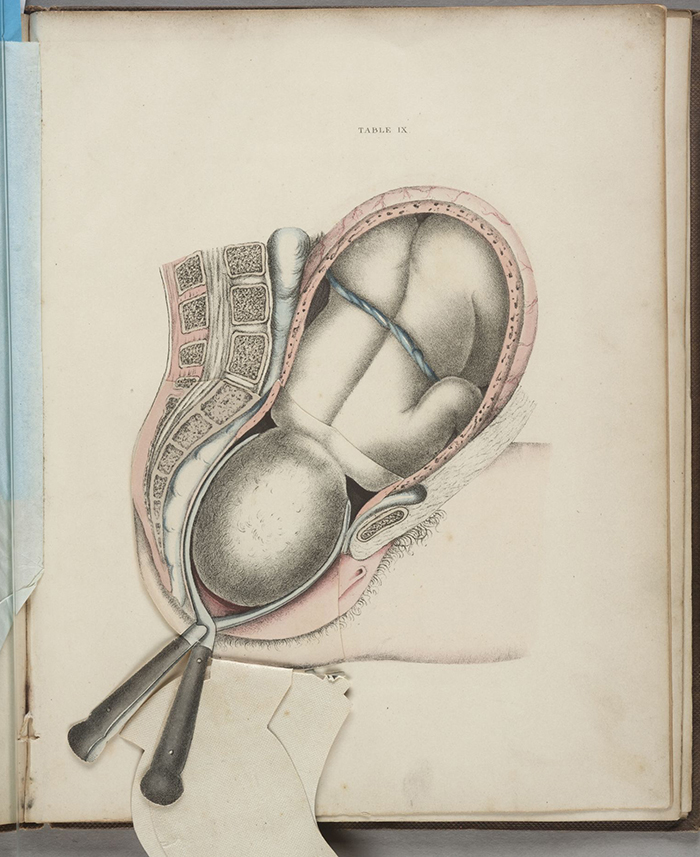

This 19th-century obstetrics textbook used fold-out flaps to help a student envision the processes of delivery. Obstetric Tables, by George Spratt, Philadelphia: Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co., No. 253 Market Street., 1848. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I joke that I always know when “my” books come up to the front desk in a research library. They are the small, brown, plainly-bound, rather battered-looking ones. Much of my scholarly work has been on medical works meant for non-medical readers: what I call “vernacular medicine.” These books, printed in small format to keep costs down (ditto the plain binding), seem to have been read a great deal; they are invariably well-worn; sometimes one of the few illustration pages is missing; and owners may have inscribed their names on the flyleaf, or, in some cases, practiced their penmanship as they wrote their name repeatedly. Occasionally a reader will have marked a text, but the elaborate humanist writing practices that decorate fancier books are rarely to be found in mine.

Those marks of use tell us something about the history of readers’ encounters with the book, and the knowledge it contained, as reading is a material practice. Kathleen Crowther, one of our speakers, recently wrote about the Renaissance use of pop-up books, now the stuff of childhood, to teach scientific and mathematical concepts; anatomy texts continued to use such devices into the 19th century. Readers touched and moved these books in order to grasp (pun intended) new concepts about the body and natural world.

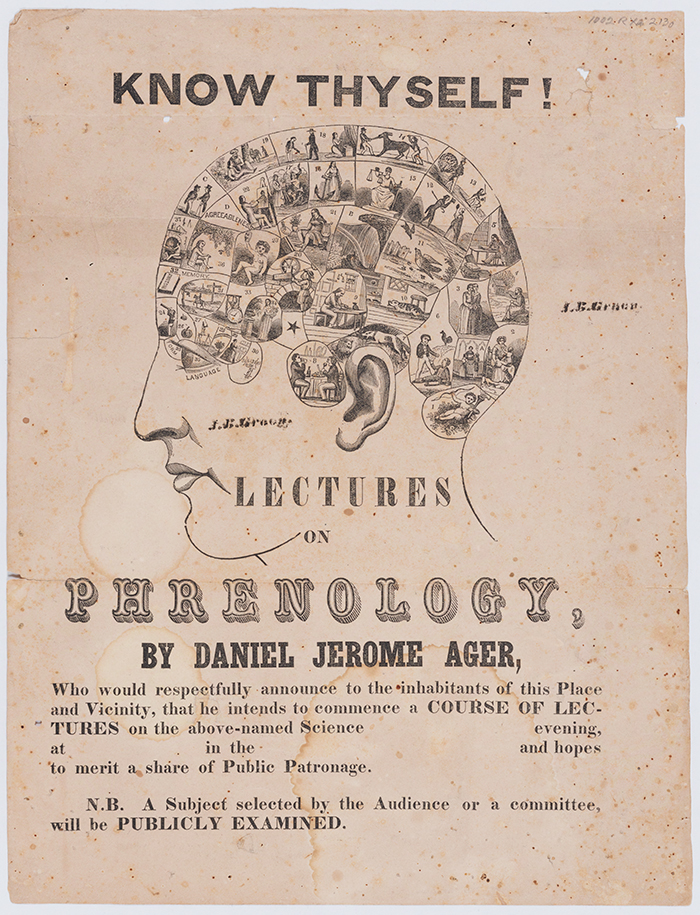

A flyer for a 19th-century course of lectures on phrenology, including a promise to examine some of the attendees phrenologically! “Know Thyself, Lectures on Phrenology, by Daniel Jerome Ager." The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Our conference brings together an array of scholars who approach the materiality of their texts in a range of ways. Some of the books we’ll consider are canonical: Vesalius’s ground-breaking anatomical work; or the 19th-century textbook Gray’s Anatomy. Others are less canonical, such as works on phrenology or home-birth newsletters, mimeographed and distributed by feminist activists in the 1970s.

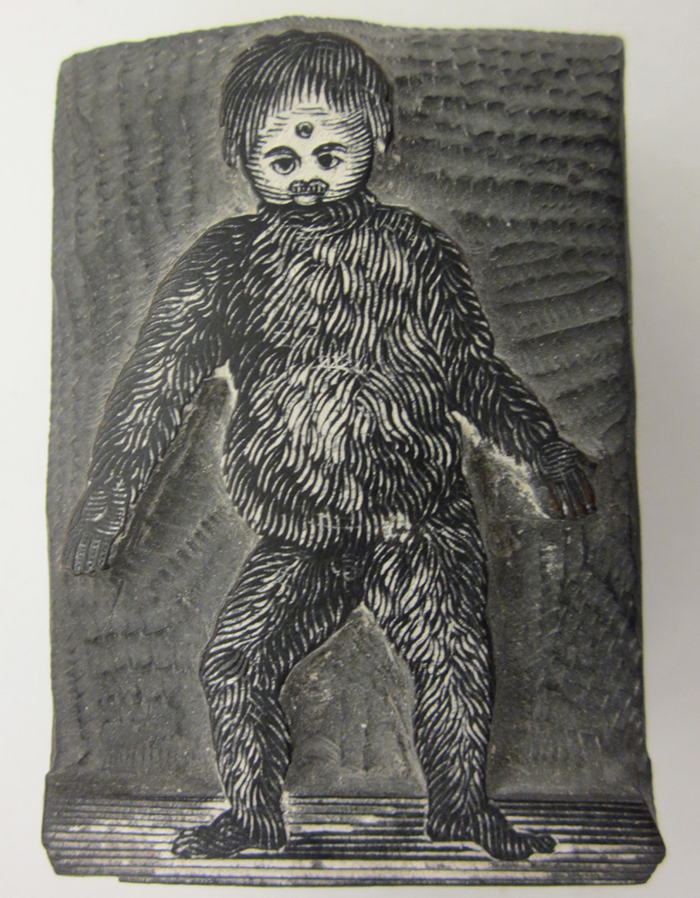

We’ll hear about the unusual red ink used to print spell-books in South Asia; and the surprising absence of illustration in some Renaissance anatomical works. We’ll eavesdrop on how readers interacted with texts, for example exploring where and how early 20th century men and women read Aristotle’s Masterpiece, the long-lived vernacular manual about sex and reproduction.

The Huntington collection includes very rare woodblocks used to create images in an early 19th-century edition of Aristotle’s Masterpiece. This image of a monstrously hairy child was reproduced in various forms for centuries. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

There is nowhere better to consider the material nature of the works we study (and the ways in which those material qualities might tell us new things about those works) than in a major research library such as the one at The Huntington, which curates and cares for a magnificent collection of medical books. We’ll also be doing break-out sessions, where small groups of participants can engage with the materiality of books by exploring medieval manuscripts; folding paper to understand how early-modern books were put together; touring the conservation department, and other related activities. My hope is that our conference will help us to better appreciate the complex relationships between the material forms of medical books and the texts they contain.

Mary E. Fissell is a professor in the Department of the History of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University, with appointments in the history of science and the history departments. Her most recent book, Vernacular Bodies: The Politics of Reproduction in Early Modern England, is available from Oxford University Press.