Posted on Tue., Nov. 20, 2018 by

Left: an image from Carolina Caycedo’s video project, Apariciones / Apparitions (2018). Right: a detail of Caycedo’s three-panel screen, To walk in the present looking forward towards the past, carrying the future on our back / Caminar por el presente mirando de frente hacia el pasado, cargando el futuro en nuestra espalda, 2018. Photo by Deborah Miller.

The exhibition "Rituals of Labor and Engagement: Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr.," which opened in the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art on Nov. 10, 2018, will remain on view through to Feb. 25, 2019. The Huntington partnered with East Los Angeles College's Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) for the third year of The Huntington's /five initiative, inviting noted Los Angeles artists Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. to create new work in response to The Huntington's collections around the theme of Identity. Carribean Fragoza, a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California, focuses in this post on the exhibition.

When push comes to shove, there are two kinds of people in the world. The kind who will either run away from a fire or a fist fight, and the kind who will run toward it to get a closer look. The spectacle of cataclysmic events can either lure or repel, depending on one's tolerance for disruptive shifts and one's stakes in what what will be lost or won. In the exhibition "Rituals of Labor and Engagement," which culminates this year's /five artist residency at The Huntington, the work of Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. mark cultural, geographic, and historic shifts that shape California's unique character as well as its prominent economic status. Each artist engages different aspects of these shifts by delving into the rituals of labor—spiritual, philosophical, and artistic. And what are rituals if not organized attempts to impose order on the seeming chaos of life?

In her video, Apariciones / Apparitions (2018), Caycedo brings brown and black bodies to supernatural life, navigating The Huntington’s grounds in uncanny ways. The dancers in this still from the video appear to melt into the landscape of The Huntington’s North Vista. Apariciones / Apparitions was choreographed by Marina Magalhães and shot by David de Rozas. Courtesy of Carolina Caycedo.

Or, perhaps, consider the opposite: What are rituals if not attempts to disrupt order as we know it? Featured prominently on the western wall of the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art, Carolina Caycedo's video disrupts the order of the traditional gallery space and calls into question social, economic, and political systems in place. The guttural sounds and moving images projected on the screen seem sharply at odds with the hushed calm of the surrounding gallery spaces filled with early American paintings and objects. Perhaps the video comes as a shock to unsuspecting visitors. On a warm Saturday afternoon, two women strolled into the room holding hands but abruptly stopped as they were confronted by the video. They chuckled nervously and turned to leave without so much as a glance at the other work.

Caycedo brings brown and black bodies to supernatural life, navigating The Huntington's grounds and buildings in uncanny ways. The dancers appear possessed as their bodies jerk, shake, and melt into each other and the landscape. Moreover, their actions implicate the artist and the viewer as they adjust (or don't) to the video's disruption of the gallery. "As artists, we have a different way of navigating the archive," notes Caycedo of her process during the residency, which followed what she describes as a "rhizomatic" path.

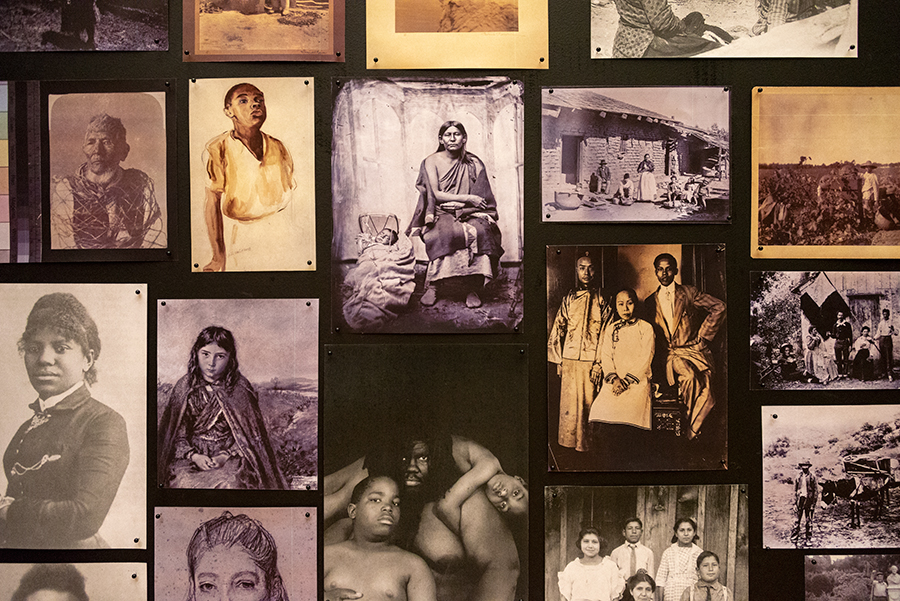

A detail of Caycedo’s three-panel screen, To walk in the present looking forward towards the past, carrying the future on our back / Caminar por el presente mirando de frente hacia el pasado, cargando el futuro en nuestra espalda, 2018, including portraits of African American, Native American, and Mexican men, women, and children. In the middle image on the bottom row, an African American man and his young sons embrace, skin to skin, finding home in one another. The man is Willie Middlebrook (1957–2012), a friend of the photographer Laura Aguilar (1959–2018), who supported and influenced Aguilar’s development as a photographer. Photo by Kate Lain.

Viewers can immerse themselves in Caycedo's nonlinear display of research and visual references on a three-panel screen onto which she groups images of plants, animals, and the people and natural topography of California as it has been displaced and reshaped. Perhaps most striking is her inclusion of portraits of African American, Native American, and Mexican men, women, and children patiently posed for the camera. In garb and posture, they bear the evidence of colonization. An African American man and his young sons embrace, skin to skin, finding home in one another, despite violent displacements suffered by people of color throughout history. (The man in the photo is Willie Middlebrook (1957–2012)—a friend of the photographer, Laura Aguilar (1959–2018); Middlebrook supported and influenced Aguilar's development as a photographer.) Interspersed throughout are self-portraits by Aguilar, who, in an act of decolonization, reintegrates her nude body into the desert landscape. Her back, breasts, and buttocks resemble the shapes of rocks and land formations rather than Eurocentric fashion or beauty norms.

For some gallery visitors, the room, with all its disruptions, is an open-armed invitation to enter. A group of teenagers shuffled in hurriedly, pulling up their sagging pants and adjusting all manner of tank tops and purse straps as they hungrily viewed each image. They hovered and moved, hovered and moved like a team of hummingbirds sipping on the bright colors of Mario Ybarra Jr.'s illustrations. Magic marker ink can be like sweet nectar for the young, who can perform miracles with nothing but overused marker tips and bled-to-death ball point pens on plain notebook paper. Many unsupervised rear rows of classrooms and poorly-lit bedrooms have served as secret studios for young artists diligently practicing their line work. In Mario Ybarra Jr.'s drawings, they see what is possible—the fruit of daily practice.

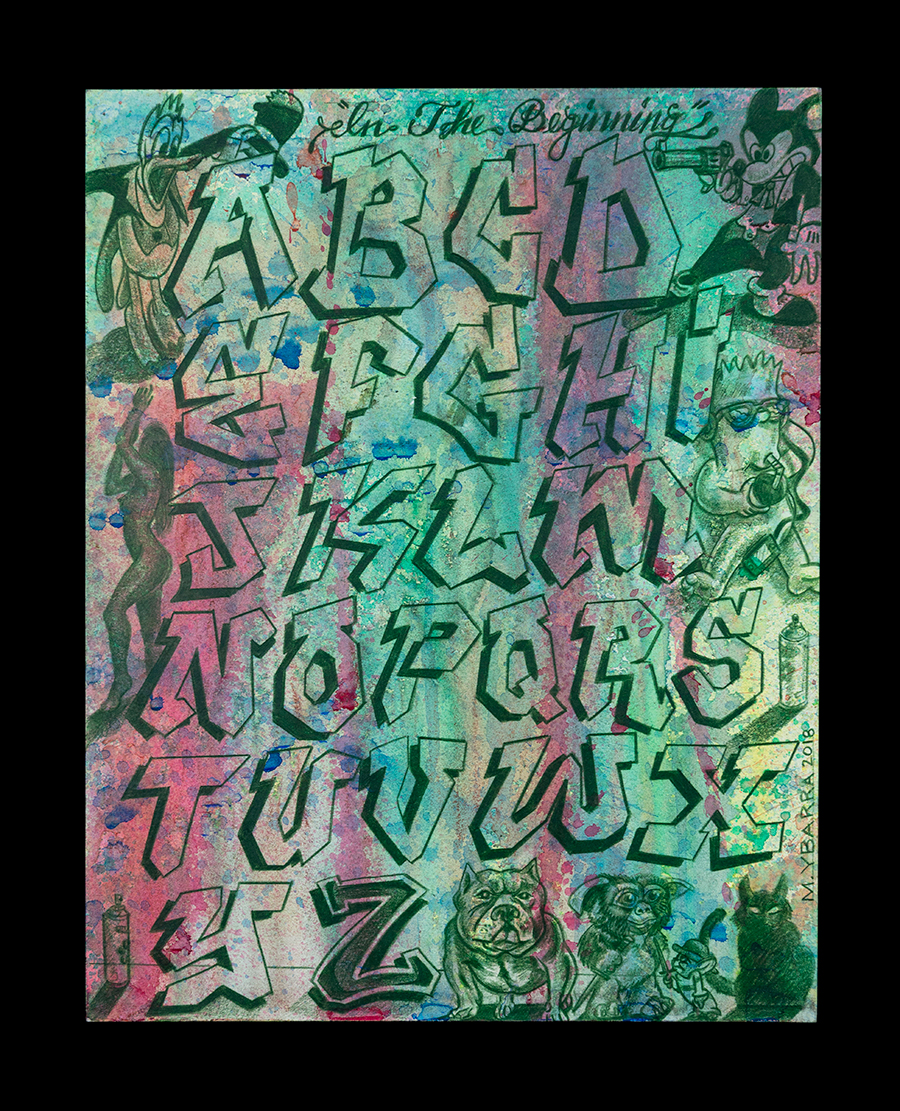

Mario Ybarra Jr., In The Beginning, 2018. Colored pencil and acrylic paint on paper, 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Ybarra Jr.'s In the Beginning is a kind of origin story for novice graffiti writers, calligraphers, scribes, tattoo artists, and all-manner of budding blue-collar artists. The graffiti-style alphabet, with cartoon characters alongside naked women, serve as basic cultural references, picked up from television or the street, learned in childhood. The drawing points to the work of repetition and ritual that must be performed again and again before the artist can ascend to higher expression and eventually achieve a unique style.

Ybarra Jr.'s drawings and etchings are introduced by some of The Huntington's Albrecht Dürer engravings and 15th- and 16th-century illuminated biblical manuscripts, masterly testaments to the rituals of a daily arts practice. They signal a return to the hand's work in making art—a turn away from highly conceptual trends in which artists outsource the labor of implementation to a team of interns and manufacturers. That's not to say that the manual labor of craft isn't cerebral, or that it doesn't engage deeply with philosophical questions. Riffing off monks' manuscripts created centuries ago, Ybarra Jr. reframes questions of good and evil, using the vocabulary and iconography of urban Chicano culture by referencing such cultural figures as Selena (the beloved Mexican American, Tex-Mex martyr), as well as Pablo Escobar and El Chapo, two of the most admired, fetishized, and despised drug lords of all time.

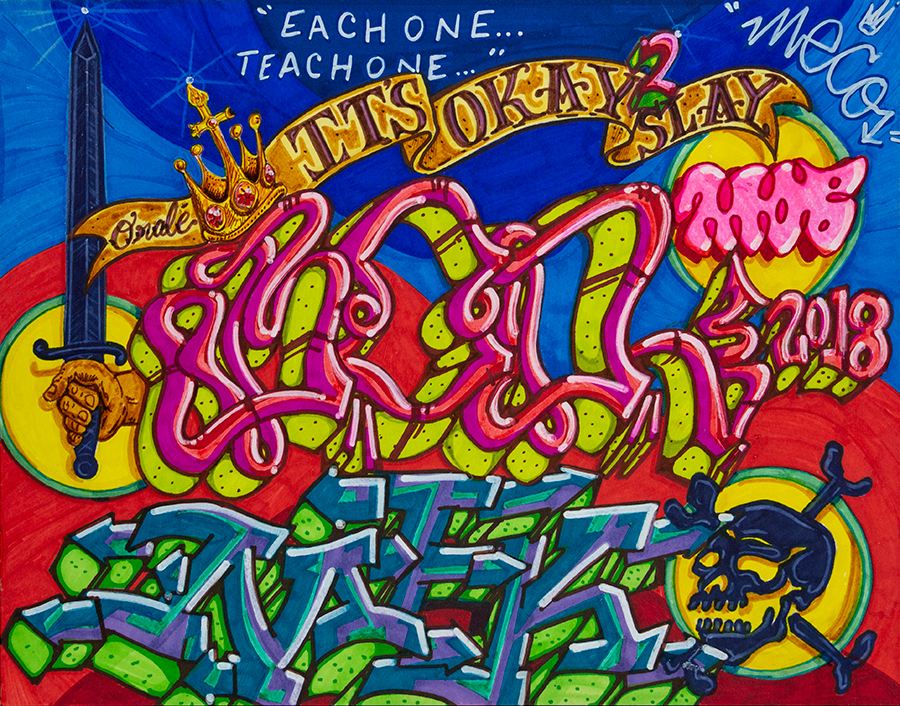

Mario Ybarra Jr., It’s Okay 2 Slay, 2018. Marker and acrylic paint on paper, 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist.

But Ybarra Jr.'s drawings are also preoccupied with other concerns more pertinent to our modern, hyper-capitalist times. In "Stacks of Bread," the artist depicts a fat stack of cash bills, for example. While, abstractly, our general culture recognizes that money is power, for people in poor and working-class communities, hustling day to day to make money, a stack of cash directly translates to bread—the difference between having a day's meal or not.

People of color have always played an essential role in California and U.S. history, not just for their raw manual labor, but also for their intellectual and cultural contributions. For them and others in this context, rituals of labor are, perhaps, more than anything, acts of survival. "Rituals of Labor and Engagement" is an intimate testament to this endurance.

“Rituals of Labor and Engagement: Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr.” is on view in the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art through Feb. 25, 2019. Photo by Deborah Miller.

You can watch a video about the exhibition and artists on YouTube.

You can listen to a musical play-list to accompany the exhibition, selected by participating artist Carolina Caycedo and her performers, on Spotify. (A free Spotify account is required to access this playlist.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by Terri and Jerry Kohl and family, the Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation, and the WHH Foundation.

Carribean Fragoza is a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California.