The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Prayer Book of Mary, Queen of Scots

Posted on Mon., Dec. 3, 2018 by

Illustration in a prayer book that once belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), Adoration of the Magi, Huntington Manuscript 1200, folio 67 verso. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The family feud between England's Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) and her cousin, the Scottish Queen Mary (1542–1587)—not "Bloody" Mary, Elizabeth's half-sister—has fascinated people since the 16th century. In 1568, Mary crossed the border into England after being forced to abdicate the Scottish throne. Mary's grandmother, Margaret, was the sister of England's King Henry VIII (1491–1547), which gave Mary a royal Tudor bloodline.

Ultimately, Elizabeth had Mary arrested and placed under house arrest after letters surfaced that made it seem as though Mary was making a play for the English throne. House arrest in the case of a queen meant a comfortable life in a secluded castle, under constant watch. It was during this period that Pope Pius V (1504–1572) allegedly sent Mary a beautifully illuminated prayer book to comfort the Catholic queen as she languished away in Protestant England.

Flight into Egypt, Huntington Manuscript 1200, folios 80 verso and 81. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

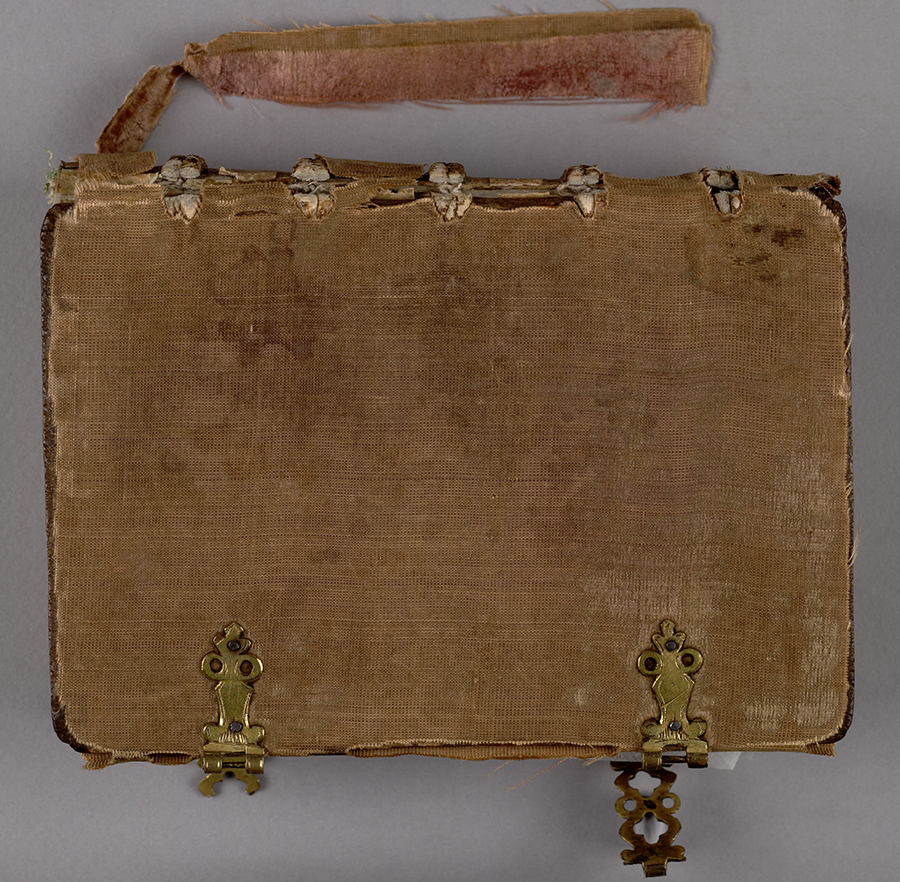

Covered in silk velvet and secured by two metal clasps, the prayer book was made in Flanders in the 15th century and contained all the standard prayers that a pious Catholic queen would need to tend to the maintenance of her soul. It was decorated with eleven full-page miniature paintings, as was customary in elaborate devotional prayer books of the day. Oddly, the borders of the decorated miniatures do not match the borders of the pages with the prayers (see above), which suggests the paintings were originally made for a different book.

After Mary spent 20 years as a royal prisoner, Elizabeth signed the death warrant calling for Mary's execution, when news of yet another plot against Elizabeth surfaced. On the morning of Feb. 8, 1587, a devout Mary approached the scaffold. In her hands, she clutched the prayer book, and her final words before she lowered her head to the executioner's block were prayers in Latin.

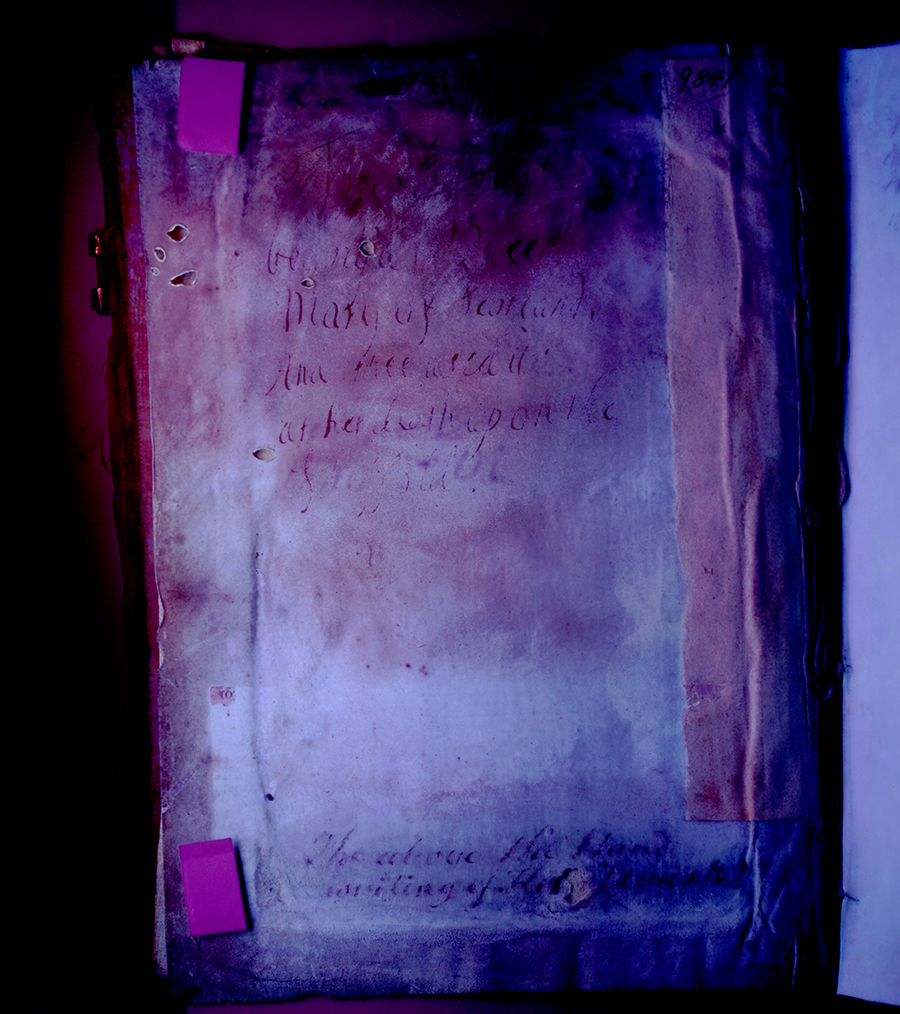

Inscription, under a blacklight, attributed to King James II (1633–1701), grandson of the Scottish Queen Mary: “This Book belonged to Queen Mary of Scotland And shee used it at her death upon the Scaffold.” Huntington Manuscript 1200, ii verso. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

After Mary's execution, her clothes were removed from her body and burned to prevent supporters turning them into relics. But her prayer book was preserved and ultimately returned to her royal family. There is an inscription on the front cover, viewable now only under blacklight (see above), that was allegedly written by her grandson, King James II (1633–1701): "This Book belonged to Queen Mary of Scotland And shee used it at her death upon the Scaffold."

The precise journey this manuscript has taken since Mary's demise is hard to follow, but it moved through England, Scotland, France, and ultimately to the United States, where, in 1918, G. D. Smith acquired it for Henry E. Huntington.

Binding, very worn pink silk velvet over oak boards with two gilt fore edge clasps. Huntington Manuscript 1200. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

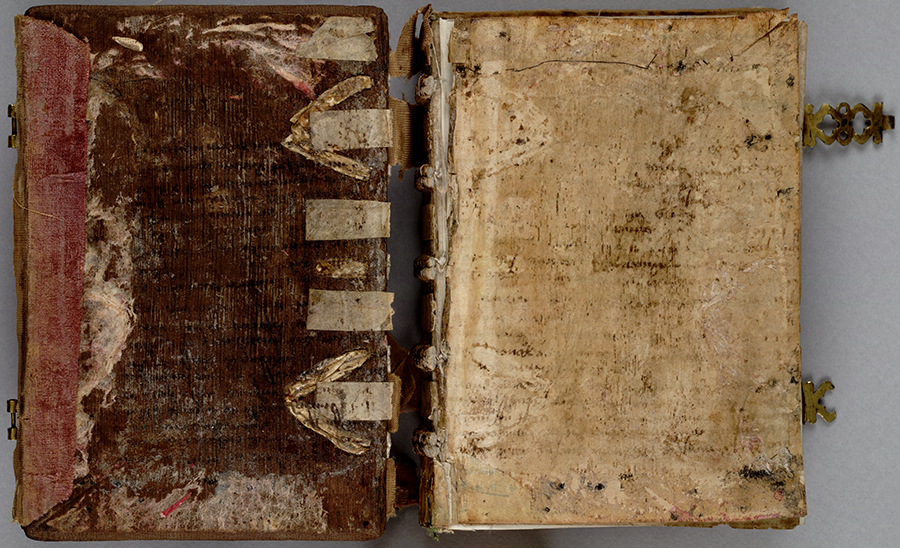

The manuscript was at least 100 years old before Mary possessed it, and today the glue on the binding, hardened over the past 500 years, has rendered the precious book virtually impossible to open safely. The manuscript is still encased in its original binding with oak boards, covered in the silk velvet, but the velvet has degraded over time and is extremely fragile.

Normally library curators and conservators would work out a treatment plan to remove some of the glue and repair the binding—and perhaps even introduce new elements that would help stabilize the book. But in this case, we are taking a different approach, as this is more than just a book. This book likely comforted a queen in her final hours and rested on the scaffold during one of the most iconic moments in English history. This book is an historical artifact, and for that reason, we are reluctant to introduce new materials and alter its original structure.

Binding inside front cover, showing pegging of the thongs and offset of the former pastedown. Huntington Manuscript 1200. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As the curator for this remarkable manuscript, I am working closely with Andrea Knowlton, senior book and paper conservator at The Huntington, to develop a treatment plan that allows us to regain access to the pages of this book while respecting its integrity as an object. We are researching cutting-edge imaging and treatment techniques and consulting with colleagues from around the world. We do not take these responsibilities lightly and know it is an honor to make the decisions regarding the care for this special item.

As we continue to research, I'll be going to a movie theater this month to watch Margot Robbie, playing Queen Elizabeth I, and Saoirse Ronan, playing the Scottish queen, face off in the film Mary Queen of Scots. I'll surely be intrigued by the politics of the story, emotional over the heartache, and enchanted by the dresses. But, most of all, I'll be looking to see if a little velvet-covered prayer book makes a subtle appearance at a crucial moment.

Vanessa Wilkie is William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History at The Huntington.