The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Venice: Real and Imagined

Posted on Wed., Dec. 19, 2018 by

William Wyld (British, 1806–1889), Doge’s Palace and Winged Lion of Saint Mark, 1835, watercolor. Gilbert Davis Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Countless novelists, composers, poets, and playwrights have sourced Italy's Venice for their creations. Somewhat less prominent on the cultural radar are the visionary developers, marketing-savvy citrus growers, and architects of expositions who have done the same.

"Venice: Real and Imagined," currently on view in the Works on Paper Room on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery, highlights the beauties of this magnetic city alongside the fanciful commercial ventures it inspired.

James Holland (British, 1800–1870), Venice, Punta della Dogana, 1864, watercolor over pencil. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

"Venice is so unbelievable, so otherworldly, that people are drawn to recreate it," says guest curator James Fishburne. He delved into The Huntington's fine art, photography, and ephemera collections to illustrate the glories of Venice and their role in the popular culture of the United States.

Representations of the city's landmarks immerse the viewer in the real Venice. An 1835 watercolor by William Wyld celebrates the Doge's Palace with its intricate Gothic tracery and its granite column capped by the winged lion of St. Mark, the city's symbol. An 18th-century etching of St. Mark's Basilica focuses on its expansive square, a beacon for tourists past and present. An Edward Lear watercolor from the 19th-century depicts the famed Rialto Bridge, which has spanned the Grand Canal since 1591. And an 1830 map shows the city's location on a lagoon and The Grand Canal winding through its center, connecting its must-see sites.

Mutual Label & Lith. Co. (American, 1899–1906), Rialto Brand Citrus Crate Label, 1900–1906, lithograph. The Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

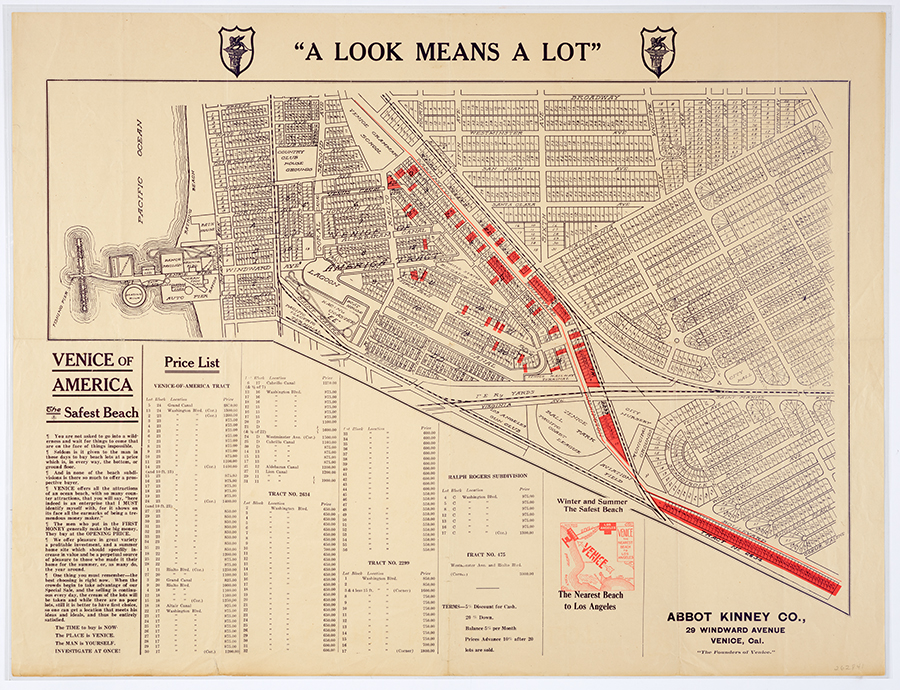

The adjoining walls of the Works on Paper Room echo these images. Representations of Venice, California, dominate. Tobacco magnate and real estate developer Abbot Kinney, perhaps the most ambitious imitator of all things Venetian, created "Venice of America" literally from the ground up, in 1905. A 1911 map from his company shows the pattern of a lagoon and two miles of canals. The arches of St. Mark's Hotel, shown in a photograph from the early 1900s, resemble those of the Doge's Palace, and a winged lion perches on one of the building's corners.

"Venice, California, is an important and fascinating place in the development of Southern California," notes Fishburne. In preparing the exhibition, he traced the "Venice of America" canals, most of which are now paved over. The large swimming lagoon of the past is now a traffic circle where Windward Avenue connects with Grand Avenue—a street that replaced a branching canal.

Unknown photographer, Gondola, Lagoon, and Midway Plaisance in “Venice of America,” ca. 1906–1910, photograph. Pacific Electric Railway Company Photographs. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One surprise of Fishburne's research: Kinney's constant revamping of Venice. Originally a small amusement park, Midway Plaisance graced the shore of the lagoon. By 1911, a state-of-the-art roller coaster called "Race through the Clouds" took its place. The only roller coaster of its kind on the West Coast, it reached speeds in excess of 70 miles per hour.

Another California city, Rialto, owes its name to the Italian Venice. The San Bernardino County city is thought to be named after a bridge, long ago destroyed, located in the city and said to resemble the original Rialto Bridge in Venice, Italy. A Rialto Brand citrus crate label, circa 1900–1906, preserves that history. The singular span still appears on the city seal with the motto: "Bridge to Progress."

In its ongoing quest to attract visitors, the Abbot Kinney Company hired a gondolier from Venice, Italy, to serenade tourists gliding through the city's canals, as seen in the photograph "Bridge and Gondola in 'Venice of America,'" ca. 1910. This idea was far from new. Gondoliers plied their trade at expositions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904. They provided a touch of romance to exploring the fairgrounds.

Abbot Kinney Co., Map of “Venice of America”, ca. 1911. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

"The Gondola Fete" at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, seems to surpass all tributes to Venice's iconic watercraft. As rendered in a large color lithograph, believed to be an advertisement, the extravaganza, set in an open-air theater, featured richly decorated gondolas as far as the eye could see and a cast of hundreds.

Italy's Venice still retains its lively spirit, according to Fishburne. On a recent visit, he surveyed the scene that James Holland painted in 1864: the "Punta della Dogana," with its customs house near the mouth of the Grand Canal, surrounded by a cluster of boats. "It's exactly that busy even today, with water traffic going in and out. Holland captured the energy perfectly."

Those who just can't get enough of Italy's Venice should visit the gallery adjacent to the Works on Paper Room to see two oil paintings: J.M.W. Turner's "The Grand Canal: Scene – A Street in Venice" and Richard Parkes Bonington's "View in Venice, with San Giorgio Maggiore."

"Venice: Real and Imagined" is on view through February 25, 2019.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.