Posted on Wed., Jan. 2, 2019 by

On Nov. 4, 2018, contemporary artist Tang Qingnian gave a calligraphy demonstration at The Huntington, sharing a Tang-dynasty era poem, “Song of Eight Drinking Immortals,” that celebrates eight scholars who were known for their love of liquor. Photo by Jamie Pham.

Tall and amiable, wearing glasses, his hair tied back in a ponytail, contemporary artist Tang Qingnian 唐慶年 stands in The Huntington’s Rose Hills Garden Courtyard on a sunny day in early Nov. 2018, facing a long table covered with white paper. For several moments, he dips a long-handled brush in a saucer of black ink set on a wheeled cart beside him, scans the paper for a moment, and then, with sure strokes, begins to demonstrate cursive script, a form of calligraphy developed during China’s Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

For more than 30 minutes, before the fascinated crowd that has gathered to watch him, Tang unhesitatingly plies the large brush as he writes the “Song of Eight Drinking Immortals 飲中八仙歌,” a 154-character poem composed in the 8th century by the famed poet Du Fu (712–770). Tang executes a choreography of movement and balance as yard after yard of the jumbo paper roll unspools, covered with his flowing black characters and soon stretching far beyond the length of the table. When the finished poem is laid out across the courtyard floor, Tang reads the poem in Chinese at an audience member’s request.

Tang Qingnian dips his brush into ink. Photo by Jamie Pham.

The completion of the poem is a physical tour-de-force, as well as an aesthetic and scholarly one, and it is not surprising to learn that the writing of such large-scale cursive calligraphy “became a kind of performance art in 8th-century China,” comments Phillip E. Bloom, the June and Simon K.C. Li Curator of the Chinese Garden and Director of the Center for East Asian Garden Studies.

On fresh lengths of paper, Tang writes a five-character couplet in clerical script, a form of calligraphy first used by government clerks during the Han dynasty. His brush saturated with ink, Tang meticulously writes bold black lines and geometric-appearing shapes. Roughly translated, the finished couplet reads: “Obtaining the pure ethers of the landscape; exhausting the grandeur of the cosmos.”

Tang Qingnian brushed the poem, titled “Song of Eight Drinking Immortals,” onto an unfurling, 40-foot blank page in the Rose Hills Garden Court. Photo by Jamie Pham.

Tang concludes his outdoor demonstration with his contemporary interpretation of a combination of clerical and seal script, an early form of calligraphy that was not standardized until the 3rd century BCE. He uses a smaller, narrower brush to write the four-character phrases: “Attain spontaneity; see true character.” (“I think these phrases refer to the idea that calligraphers should strive to perfect their mind and body so that they can react spontaneously and properly to any situation they might face,” Bloom explains later. “Commentators on Chinese calligraphy have long claimed that calligraphy directly expresses one’s ‘true character.’”) The characters are long and pictographic, markedly different from the preceding styles, and “more primitive,” Tang says.

Tang and Bloom then move into Rothenberg Hall for Tang’s presentation, “How to Appreciate Chinese Calligraphy,” followed by a lively Q&A session with the audience. Screening vivid images, Tang expounds on the five types of calligraphic script—seal, clerical, cursive, running, and regular—and the technicalities of brush stroke strength, lines and space, and the importance of the characters’ posture and balance.

Most importantly, he says, it isn’t necessary to be able to read what is written because how calligraphy is viewed is subjective; it can be seen “as abstract painting” or appreciated for the musicality of its rhythm and flow. Indeed, Tang says, there are some 40,000 Chinese characters, and even experts know only a fraction of that total. The work of master calligraphers, he adds, “reflects their feeling and expression” as individuals and as artists. (In an interview earlier in the day, Tang said, “We respect tradition, but we try to do something deeper than tradition. I have my own style, but it must be readable.”)

Aric Allen’s video of the calligraphy demonstration.

Tang, who works in several mediums, including conceptual and sculptural art, has demonstrated calligraphy during the Chinese New Year festival in The Huntington’s Chinese Garden for many years. A former art critic in China, he was involved in China’s “New Wave” art movement and was co-curator of Beijing’s notorious 1989 “China/Avant-garde” exhibition, closed down on opening day when one artist pulled out a gun and shot her own artwork. It was closed again due to a bomb threat.

Moving to the U.S. in 1991, Tang worked in advertising as a creative director until 2006, when he became a full-time independent artist. He has written four inscriptions for the final phase of the expansion of the Chinese Garden, set to open in February 2020. These include calligraphic inscriptions of poetic couplets carved into wood and name placards carved into wood and rock.

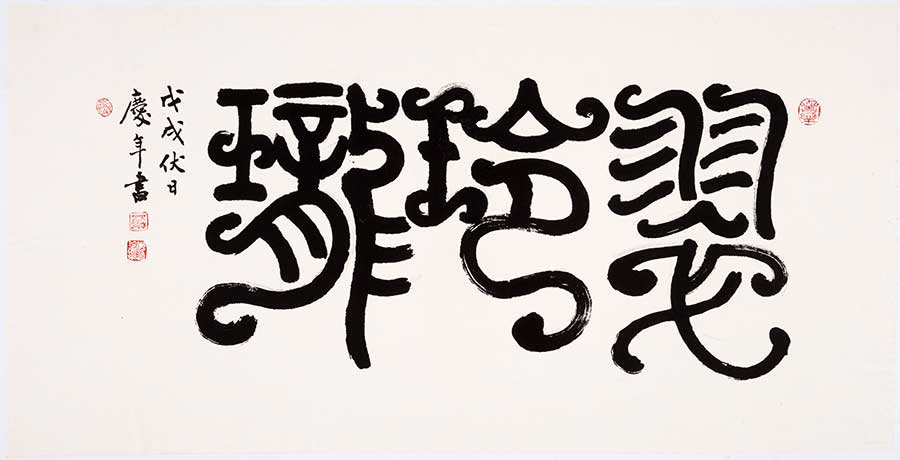

An inscription for the final phase of the expansion of the Chinese Garden, set to open in February 2020, by Tang Qingnian (Chinese and American, b. 1956): Verdant Microcosm 翠玲瓏, 2018. Handscroll, ink on paper; calligraphy written in bird-and-worm script (鳥蟲書). Unmounted: 50 x 99.8 cm. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Lynne Heffley is a freelance writer and editor based in South Pasadena, Calif.