The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

From the Mountains to the Garden

Posted on Wed., Jan. 16, 2019 by and

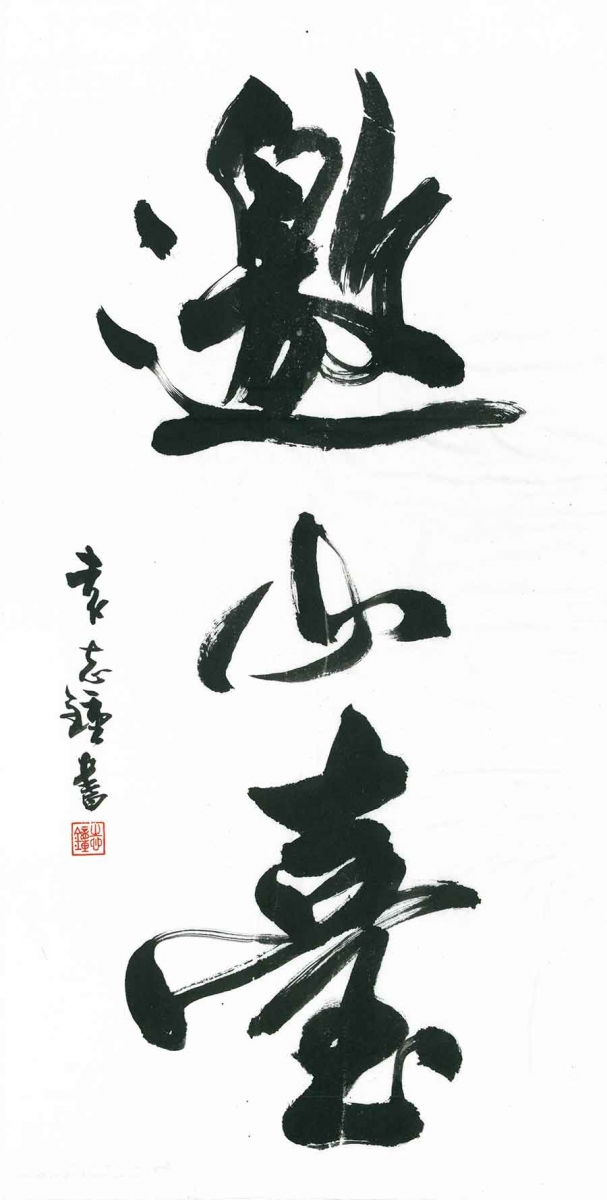

Terrace that Invites the Mountain 邀山臺 (Yao Shan Tai), 2007, by Terry Yuan (Yuan Zhizhong 袁志鍾, b. 1954 in Shanghai). Calligraphy written in semi-cursive script (行書), ink on paper, 68.5 x 35 cm. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In just three characters, Terry Yuan's calligraphic Terrace that Invites the Mountain—now carved into a rock in The Huntington's Chinese Garden, Liu Fang Yuan—captures one of the key principles of Chinese garden design: bringing nature into the garden. Rocks and water are the foundational features of the garden. Trees, shrubs, and ornamentals both on land and on the surface of the water bring the landscape to life.

Chinese horticulturalists have long engaged in domesticating plants. Domestication sometimes literally meant bringing plants from the wild, cultivating them, and breeding them to accentuate such desired characteristics as their size, the variegation of their leaves, and the colors and fragrances of their blossoms. The history of these diverse processes will be the focus of a public symposium titled “From the Mountains to the Garden: The Domestication of Garden Plants in China,” organized by The Huntington’s Center for East Asian Garden Studies. The symposium will take place on Saturday, Feb. 16, 2019 in Rothenberg Hall.

Camellia reticulata, Zixi shan紫溪山, Yunnan province. Photo by Nicholas Menzies.

Some plants take their place in gardens as markers of the passing seasons. The camellia, which blooms during winter, is known to have been brought into the gardens of southern China from its nearby native mountain habitats as early as the sixth or seventh century. Scholars transplanted fine specimens from the wild, and a horticultural manual from 1719 recommends that, for best results, they should be potted in some of their original soil.

As winter turns to spring, the peony brings a spectacular burst of color to the garden. There are records of peony cultivation as early as the fifth century. The peony has been celebrated since then in poetry, plays, and paintings as a beloved flower whose blooming enlivens the mid to late spring. It is only recently, though, that research into the genetics of the peony has shown that the ornamentals we know today are most likely the product of the independent domestications of cultivated plants from distinct species and locations at different times.

Peony (Paeonia lactifloria), Liu Fang Yuan 流芳園, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Norma Lee.

Some plants have been a feature of gardens for so long that it is hard to tell where they originally came from, who domesticated them, and when. For many centuries, the ginkgo’s longevity and golden fall foliage have made it a feature of temple gardens in East Asia, and, more recently, of urban landscapes in Europe and the United States. Until very recently, though, botanists were not sure whether any ginkgo trees still existed in the wild. Careful detective work using fossil records, DNA analysis, and historical texts from China have helped to reconstruct the ginkgo’s past, highlighting the importance of its popularity as an ornamental garden tree to the species’ survival.

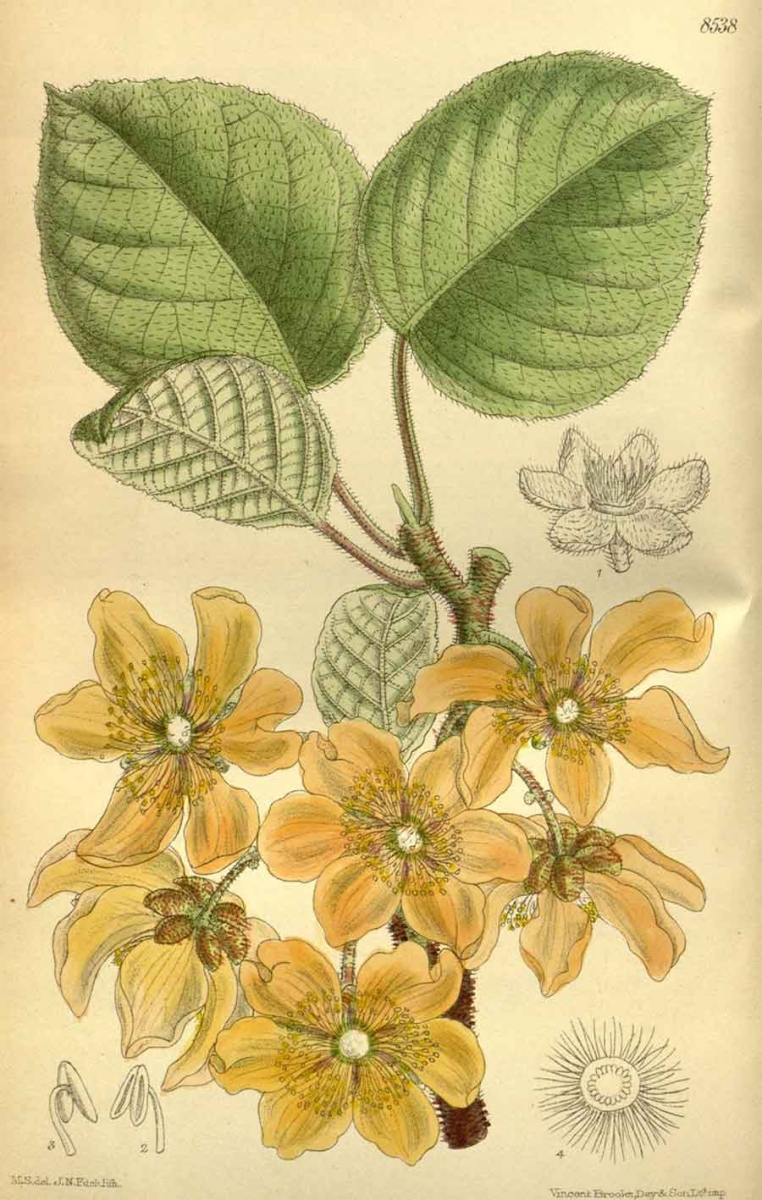

Selection and breeding have often dramatically changed the appearance of plants—and even their taste—as is the case with the fruit of the Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa, once commonly known in English as the Chinese gooseberry, and now much better known as the kiwifruit. There are more than 400 varieties of the fruit in China, where it has been cultivated for at least 300 years. The fruit was introduced to New Zealand in 1910 and, after intensive breeding, became known to the world in the 1970s as the ubiquitous fuzzy brown fruit with sweet green flesh.

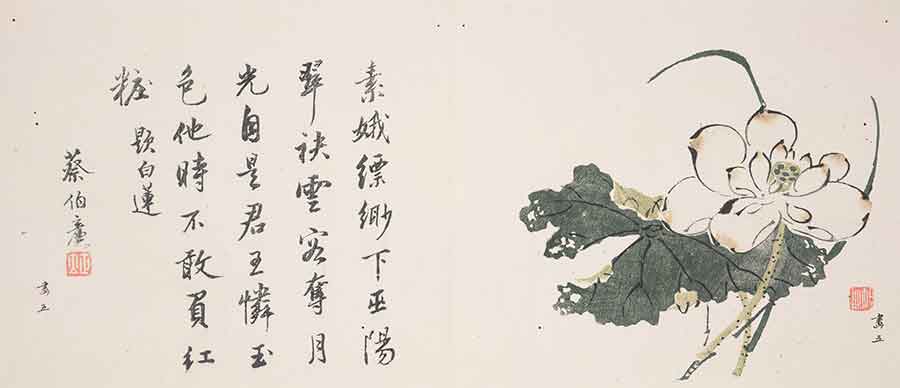

The lotus 蓮 (Nelumbo nucifera) has been a feature of ponds and lakes for such a long time that it is only through studies of its genome that it has been possible to trace its ancestry and origins. Woodblock image of a lotus by Hu Zhengyan 胡正言 in Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting 十竹齋書畫譜 Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu, vol. 3, fig. 5. Liu Fang Yuan Garden Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

At the symposium, scholars from China, the United States, and France will speak from different perspectives about the ginkgo, the lotus, kiwifruit, camellia, peony, and more recently introduced plants from the mountains of southwestern China. Their papers will address such topics as how sources, ranging from historical and literary records to DNA analysis, can be used to understand domestication; the origins and distribution of important garden species; and the horticultural techniques involved in domestication. The gathering will provide a rare opportunity to hear specialists from different disciplines give their insights into how humans and our gardens have played a role in shaping some of the plants we see around us every day.

Chinese gooseberry/kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis), hand-colored lithograph by Matilda Smith, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 1914. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Nicholas Menzies is a research fellow at the Center for East Asian Garden Studies at The Huntington.

Phillip E. Bloom is the June and Simon K.C. Li Curator of the Chinese Garden and director of the Center for East Asian Garden Studies at The Huntington.