Posted on Wed., Jan. 9, 2019 by and

Attributed to the school of Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619), Elizabeth I (1533–1603), 1590, Jesus College, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

On March 24, 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died, and James VI of Scotland was proclaimed James I of England. There was widespread relief and rejoicing that the transition happened so smoothly, for worries about the succession had persisted throughout the Virgin Queen's reign, and James's title was hardly unassailable. "Never people so happye, yf Wee have grace to see & feele our owne happiness," remarked the lord keeper, Thomas Egerton (1540–1617), Lord Ellesmere, whose papers are housed here at The Huntington.

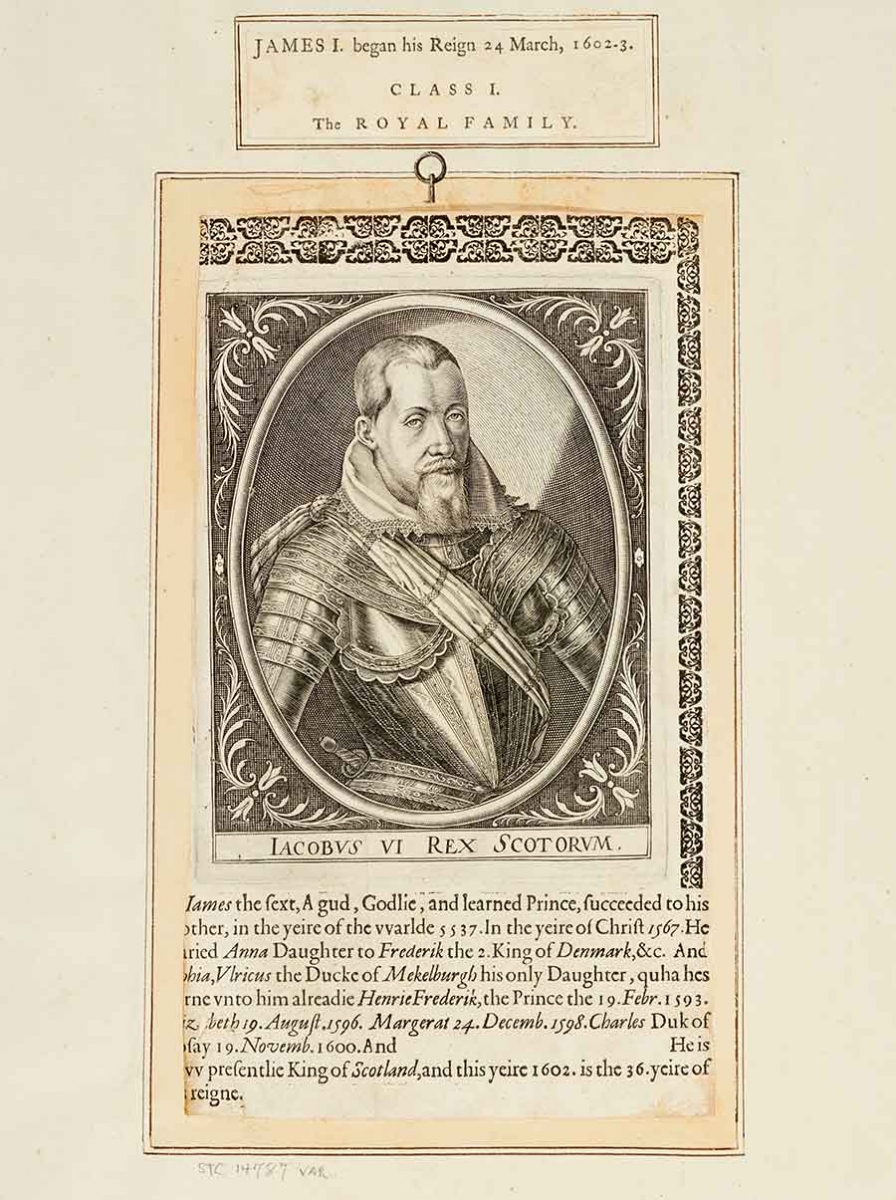

Printing presses in London churned out poems of praise, genealogies, sermons, succession tracts, addresses, and ballads welcoming the new king and counseling him on how to rule. There were numerous engraved likenesses of James. Enterprising publishers hastily issued editions of his own prolific writings on monarchy and governance, religion, poetry, and many other topics. For how else would his subjects get to know him?

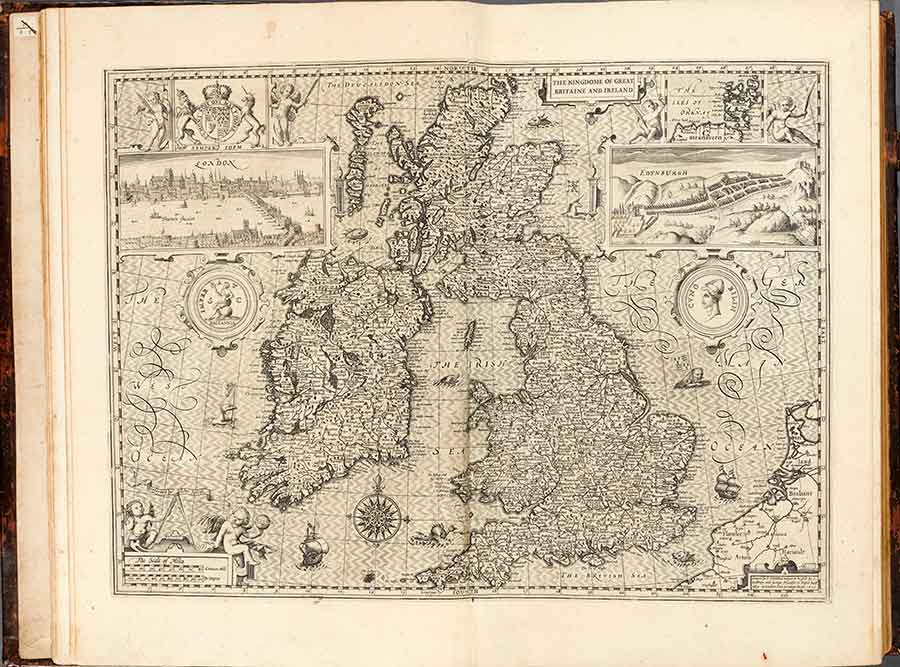

At 37, James was still relatively young, and brought with him a queen-consort, Anne of Denmark; an heir, Prince Henry; and two spares. For the first time in over half a century, the country had a royal family. And, after centuries of dissension, England and Scotland were now united under one scepter. No wonder many saw in the Jacobean accession the hand of providence. But would the new monarch manage to effect a closer union between the two kingdoms? How would he deal with deepening divisions between Protestants and Catholics, with foreign policy, with the always precarious royal finances?

Engraving of James I, from Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution, 1769, extra-illustrated by Richard Bull (1725–1806). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The change of dynasty from the Tudors to the Stuarts is a watershed in British history. There are many reasons for this, most of them discernible only in hindsight, since the change of dynasty brought complex political and religious conflicts that ultimately led to the British Civil Wars. In modern parlance, this dynastic transition is often described as a “regime change,” but what did and did not change are the subjects of our conference, titled “1595–1606: New Perspectives on Regime Change,” which will take place Jan. 11–12, 2019, in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall.

The concept of regime change is fairly recent. It acquired its current meaning of a change in government only in the 1920s. The term prompts us to ask questions that enlighten us on what royal government was and did in the early modern period. Europe then was full of composite states that had multiple forms of government under a single head—Spain and the Holy Roman Empire are obvious examples. So, what was different about the Tudor-to-Stuart transition? Did governance in either England or Scotland change dramatically? Why did the failed union of Scotland and England trigger such important constitutional debates?

As Elizabethans knew, monarchy is always alive. Though encapsulated in a person, it survives the mortal that wears the crown. When Elizabeth died, that principle was maintained by her court, where all routines remained the same, as if she were alive, even though, as the Venetian ambassador observed, she was wrapped in lead. While the monarchy was semper virens (“always flourishing”), it was not semper eadem (“always the same”). The personality and personal situation of the new king would make a huge difference at the center of the states he governed.

Engraving of James I on horseback with the City of London behind him, from Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution, 1769, extra-illustrated by Richard Bull (1725–1806). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Courtiers recognized this, so there was an opportunistic scramble for position and patronage in James’s court. The new king complained that so many English people were rushing north to meet him that the nation’s rulers were neglecting to rule. He ordered them back home to do their duties.

For some on both sides of the border, the change of dynasty meant radical displacement. The border between Scotland and England, militarized for centuries and run by wardens who chased criminals back and forth, disappeared. This left confusion in its wake, and displacement. As Sir Robert Carey, Warden of the Eastern Marches of England, said, his life as he knew it had ended. That is why he rode hell-for-leather for Scotland to be the first to tell King James he had inherited England. Carey hoped for a place in the new King of England’s court. He got it, and yet was bitterly disappointed when he was forced out by councilors offended by his corrupt ambition.

With the exception of the Borders, governance in England and Scotland did not change much. As was normal in composite states, local machinery continued to do its duty. James immediately confirmed the warrant of Elizabeth’s Privy Council to govern and then added a number of his own men. The central institutions of the state continued to be led by many of the same people and to carry on in their normal courses. Their scribes dutifully changed their forms, dating from the first day of King James I and invoking his authority, but their processes changed little.

Engraving of James I and his spouse, Anne of Denmark, from Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution, 1769, extra-illustrated by Richard Bull (1725–1806). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

There had been fears of civil war when Elizabeth died, but when it became apparent this would not happen, minds turned to fulfilling the new king’s pleasure. In this, the impact of regime change became more and more real. There was great hope invested in King James. Catholics hoped for more toleration; Puritans hoped to get rid of the obnoxious bishops. Merchants hoped monopolies and patents would be ended. And many hoped for largesse from a gracious king after the long drought caused by Elizabeth’s parsimony.

These hopes were often unfulfilled, probably because so much expectation had been projected onto James. In turn, he and his Scots courtiers projected hopes onto England, hopes that also could not be fulfilled. By 1604, his Privy Council was warning him that he could not afford his lifestyle, even though he had managed to end the wars with the Spanish and the Irish rebels.

Regime change was a moment of hope that was tightly restrained by the managerial realities of rule in composite states. Much of what was anticipated failed to materialize, but James’s convictions and personality changed England in ways that would not have occurred if someone else had assumed the throne.

“The Kingdome of Great Britaine and Ireland,” from The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain, 1676, by John Speed (1542–1629). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

No matter who the monarch was, that person was expected to inscribe their own values onto their various territories. This James did, and our conference takes a fresh look at the how and the why.

Norman Jones is professor of history at Utah State University.

Paulina Kewes is professor of English literature and Helen Morag Tutorial Fellow at Jesus College, University of Oxford.