The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Cultural Exchange During the Peace of Amiens

Posted on Wed., May 15, 2019 by , and

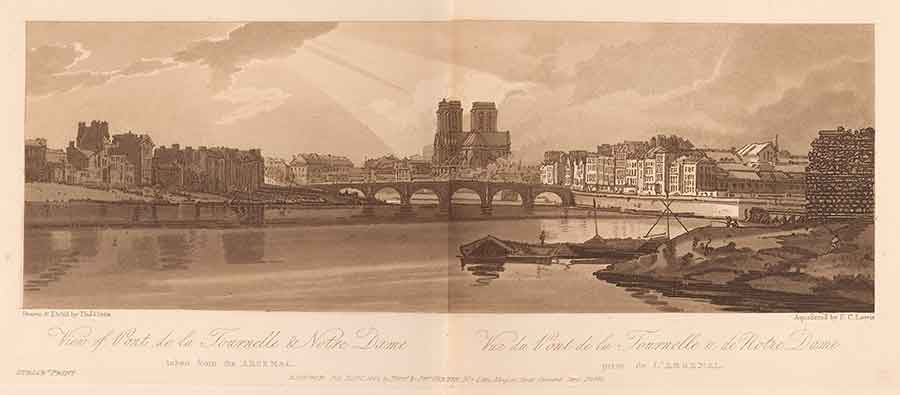

Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), “View of Pont de la Tournelle and Notre Dame,” etching and aquatint, plate 11 from A selection of twenty of the most picturesque views in Paris, and its environs drawn and etched in the year 1802 . . . and aquatinted in exact imitation of the original drawings (London: M.A. & J. Girtin, 1803). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On March 27, 1802, Britain and France signed the Treaty of Amiens, ending a decade of warfare between them that had been triggered by the French Revolution. This tumultuous period was marked not only by widespread death, destruction, and political upheaval, but by a near-complete rupture in the regular cross-Channel travel and correspondence that had shaped French and British cultures in the 18th century.

Following the agreement for a preliminary peace in October 1801, British and French travelers had begun to set off across the Channel, eager to renew contacts and learn about the latest developments in art, science, and technology. Within a week, the French representative in London complained that he was overwhelmed with requests for passports. With the signing of the Treaty in March, this trickle of travelers became a flood. According to one estimate, there were as many as 12,000 British subjects in Paris in September 1802, when the exhibition of new works of art known as the “Salon” opened in the Louvre.

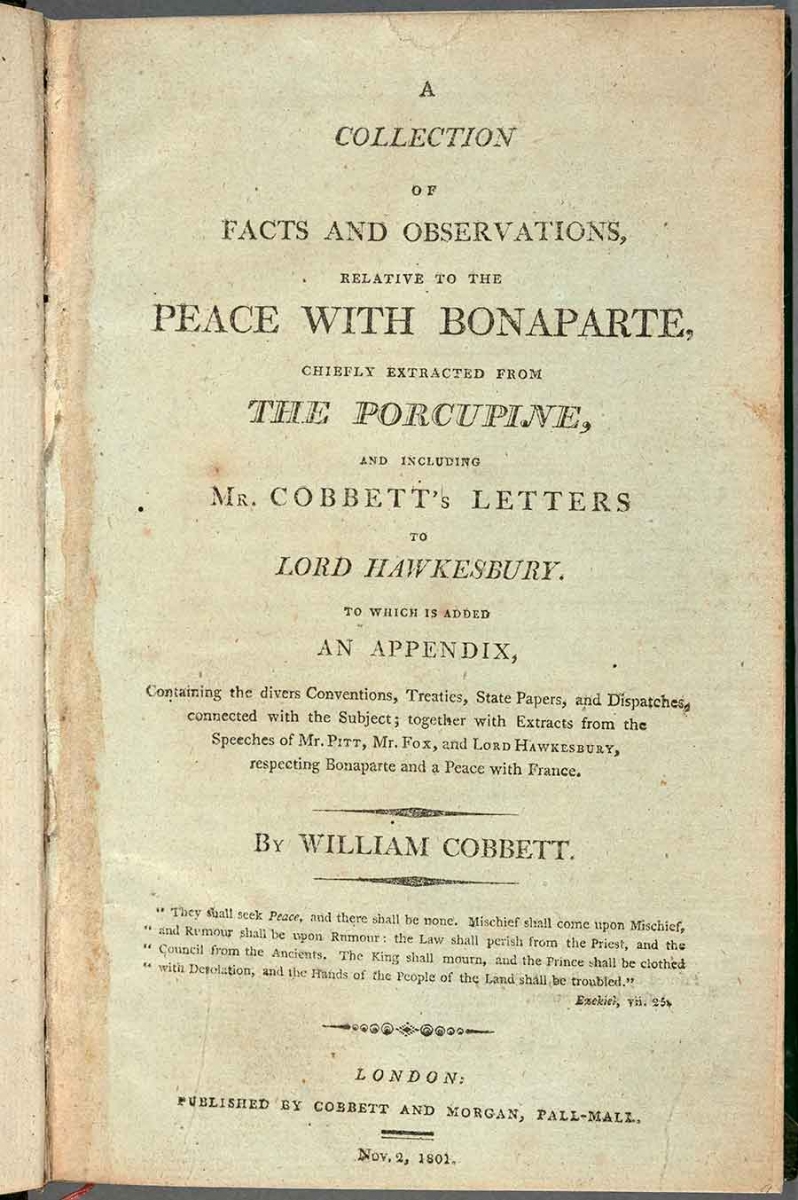

William Cobbett (1763–1835), title page of A Collection of Facts and Observations, Relative to the Peace with Bonaparte . . . (London, 1801). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The flurry of people (and goods) crossing the Channel lasted only 14 months. May 1803 marked the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), another decade of cultural isolation despite consistent, renewed attempts to break through the wartime blockades. Nevertheless, the Peace had a lasting, cross-Channel influence.

Scholars have spilled considerably more ink on the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars than on the brief interregnum of peace between them. A search of the Huntington Library’s holdings provides some insight into political reactions (skeptical and patriotic) to the prospect of peace, but little hint of the excitement it caused among artists, writers, and savants.

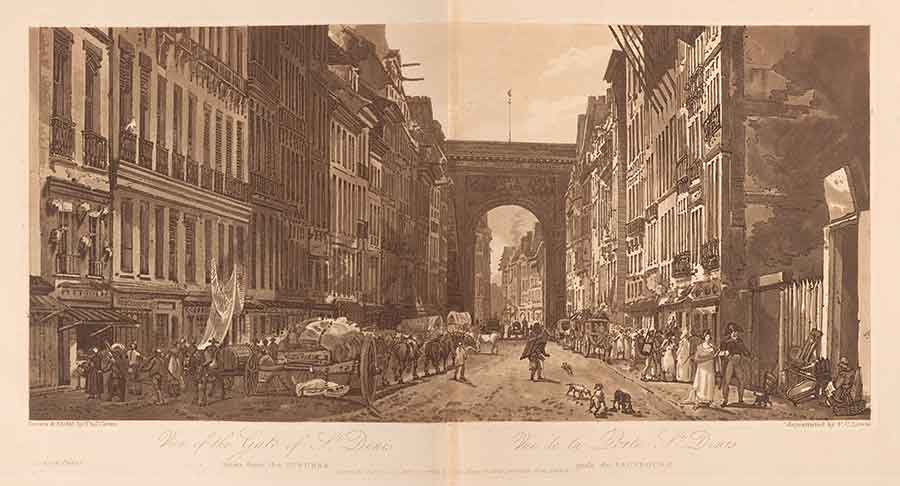

Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), “View of the Gate of St. Denis,” etching and aquatint, plate 10 from A selection of twenty of the most picturesque views in Paris, and its environs drawn and etched in the year 1802 . . . and aquatinted in exact imitation of the original drawings (London: M.A. & J. Girtin, 1803). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

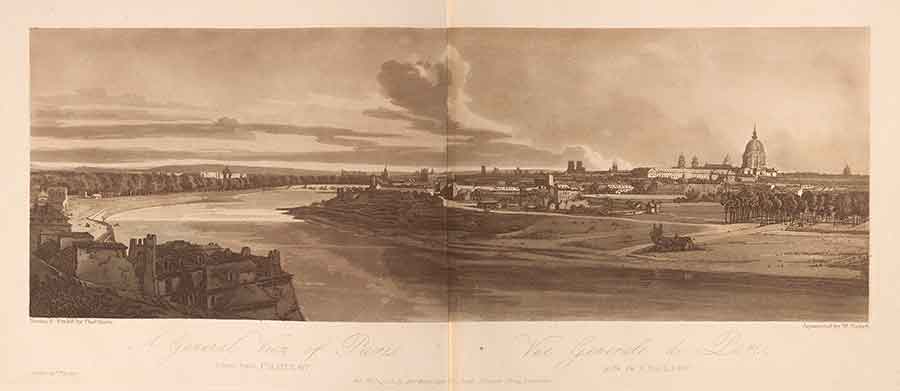

Some were eager to see the newest works of art at the Salon, some the treasures of Italy and Egypt brought to Paris by the triumphant French armies, and still others to observe the learned meetings of the new Institut de France. However, Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s associate curator for British art, has brought forth from the Library an exceptionally rare copy of Thomas Girtin’s A selection of twenty of the most picturesque views in Paris, and its environs drawn and etched in the year 1802 ... and aquatinted in exact imitation of the original drawings. Girtin was among that first wave of British artists so eager to see Paris that he went there in November 1801, as soon as the preliminary peace treaty was signed. When he returned to London the following May, Girtin made etchings based on his pencil drawings and watercolors. But although the Peace of Amiens was brief, Girtin did not live to see either its end or the publication of his etchings. After his untimely death from tuberculosis in the fall of 1802, his widow and his brother saw them through the press.

McCurdy will discuss this important work by Girtin in her contribution to a conference dedicated to this rich and fruitful period of cultural exchange between Paris and London during the Peace of Amiens, “1802: Cultural Exchange During the Peace of Amiens,” which will take place in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall on May 17 and 18. Other speakers will consider such visitors to London as Alexandre Brongniart, geologist and director of the Sèvres porcelain factory, and Marie Tussaud, whose wax tableaux representing dramatic episodes in recent history contributed to British understandings of the French Revolution. English writers Helen Maria Williams and Amelia Opie, as well as orientalist Alexander Hamilton are among the visitors to Paris who will be discussed, along with the circulation of new textile designs and “lascivious goods.” Why, we want to know, did artists, writers, and scientists in particular jump at this opportunity to travel to Europe’s other great capital? What did they do while there, whom did they see, and what ideas or objects did they take back home? What impact did the cultural exchanges made possible by the Peace of Amiens have on both sides of the Channel?

Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), “A General View of Paris,” etching and aquatint, plate 5 from A selection of twenty of the most picturesque views in Paris, and its environs drawn and etched in the year 1802 . . . and aquatinted in exact imitation of the original drawings (London: M.A. & J. Girtin, 1803). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As Brexit looms, we look forward to exploring this brief moment of peace, just over two centuries ago, when artists, writers, scientists, scholars, and manufacturers from France and Britain eagerly and profitably renewed the cultural and intellectual exchanges that have always enriched both countries when they have not been torn apart by political rivalry and war.

You can read more about the conference program on The Huntington's website.

Dena Goodman is the Lila Miller Collegiate Professor of History and Women’s Studies Emerita at the University of Michigan.

Paris Amanda Spies-Gans is a Junior Fellow in the Society of Fellows at Harvard University.

Cora Gilroy-Ware is an art historian in the London studio of Isaac Julien.