The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Making Ink from Oak Galls

Posted on Wed., May 1, 2019 by

Kelly Fernandez, head gardener of the Herb and Shakespeare gardens, and Joel Klein, Molina Curator for the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, make iron gall ink, using a recipe from the 1600s. Photo by Deborah Miller.

Kelly Fernandez, head gardener of the Herb and Shakespeare gardens at The Huntington, and her team of docent volunteers are always on the lookout for plant materials that make a good natural dye. They have used the common weed oxalis to dye yarn a bright, neon yellow. They have made dark red dyes from madder root and vivid blues from indigo.

Recently, they became interested in making iron gall ink, the dark, indelible ink made from oak galls and used for centuries to create manuscripts, including many of those in The Huntington’s library collections. “We started looking into gall ink and just got really fascinated with it,” Fernandez said. “The more we dug in, the more we found.”

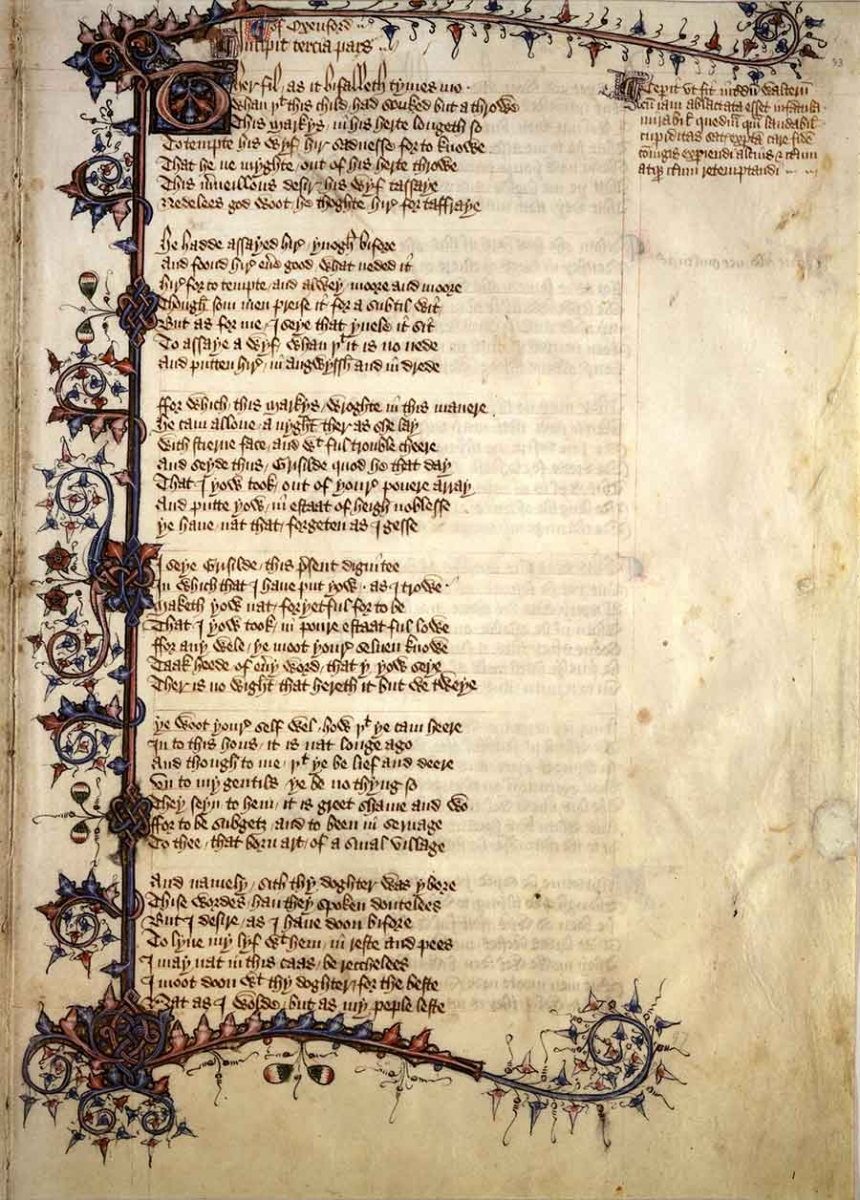

The Ellesmere Chaucer, a beautifully decorated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, was created between approximately 1400 and 1410, using iron gall ink for the text lettering. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The ink gets its name—and much of its color—from oak galls, structures that grow on oak leaves and twigs in response to attacks by wasps and other insects. The galls, created through a combination of plant hormones and chemicals released by insects, are rich in tannins, substances that help protect insect larvae maturing inside the galls. Tannins also provide a color source for dyes and inks.

A first step for Fernandez was to find galls on The Huntington’s grounds. For help, she enlisted Tim Thibault, The Huntington’s curator of woody collections, who is deeply familiar with the garden’s oaks and the various insects that inhabit them. Female wasps lay eggs and inject chemicals into trees to stimulate the formation of a gall, which provides nutrition and protection to their larvae, which hatch, emerge, and, once they mature into adult wasps, go on to lay their own eggs on leaves.

An oak gall with visible wasp larvae exit holes sits on the branch of a healthy oak on the grounds of The Huntington. Photo by Aric Allen.

Thibault said galls have been plentiful in recent years because they are more common in drought-stressed trees. To look for galls, he headed straight to a cluster of southern live oaks at the edge of the Shakespeare garden that were so riddled with galls a few years ago, some gardeners suggested the trees be treated. Thibault argued against that, saying the trees were still healthy. “Galls aren’t really a problem,” he said. “They’re just a way for a tree to defend itself.” After this year’s rainy winter, the trees look far healthier, and the galls were indeed a little harder to find.

Tim Thibault, the curator of woody collections at The Huntington, searches for oak galls. Photo by Aric Allen.

After collecting about a dozen galls with Thibault, Fernandez enlisted the help of another Huntington expert to help make the ink. Joel Klein is the Library’s Molina Curator for the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences and an expert on early-modern chemistry. In his previous position at Columbia University, he worked on “The Making and Knowing Project,” an effort that sought to recreate centuries-old recipes, crafts, and dyes, including, of course, iron gall ink. “It’s something that’s likely been used since ancient Roman times and was then popularized in the Middle Ages,” Klein said. “Many medieval scribes walked around with a kit that included a pen knife, several quills, and an inkhorn full of gall ink.”

A chemical reaction between iron and plant tannins gives iron gall ink its characteristic dark color. Photo by Deborah Miller.

To make the ink, Klein and Fernandez pulverized oak galls, added water, and then boiled the light brown extract that resulted. They filtered the extract through cloth, and Klein then sprinkled a teaspoon of iron sulfate into the extract. The solution immediately blackened. The color of the ink, Klein said, results from the chemical reaction between the iron and the tannins. Klein then thickened the ink by adding gum arabic.

In general, iron gall ink is easy to make, but early chemists had to be careful with their recipes because the iron in the ink could be corrosive. “A poorly made ink can eat right through a page,” Klein said. Iron gall ink was preferred over other inks made from soot or lampblack because it lasted so well; it was the predominant ink for centuries, Klein said, until the advent of the printing press, which required an oilier and stickier ink.

A collection of the materials used to make iron gall ink, yarn dyed with the ink, and ink used on paper. Photo by Deborah Miller.

If you are interested in seeing iron gall ink, or items that have been dyed with it, attend Fiber Arts Day this Saturday, May 4, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the Herb Garden. The event will feature numerous displays and craftspeople from five Southern California craft guilds. They will demonstrate a wide variety of fiber arts, including dyeing, spinning, weaving, and quilting.

Usha Lee McFarling is the senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.