The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Sesquicentennial of a Railroad Across America

Posted on Wed., May 8, 2019

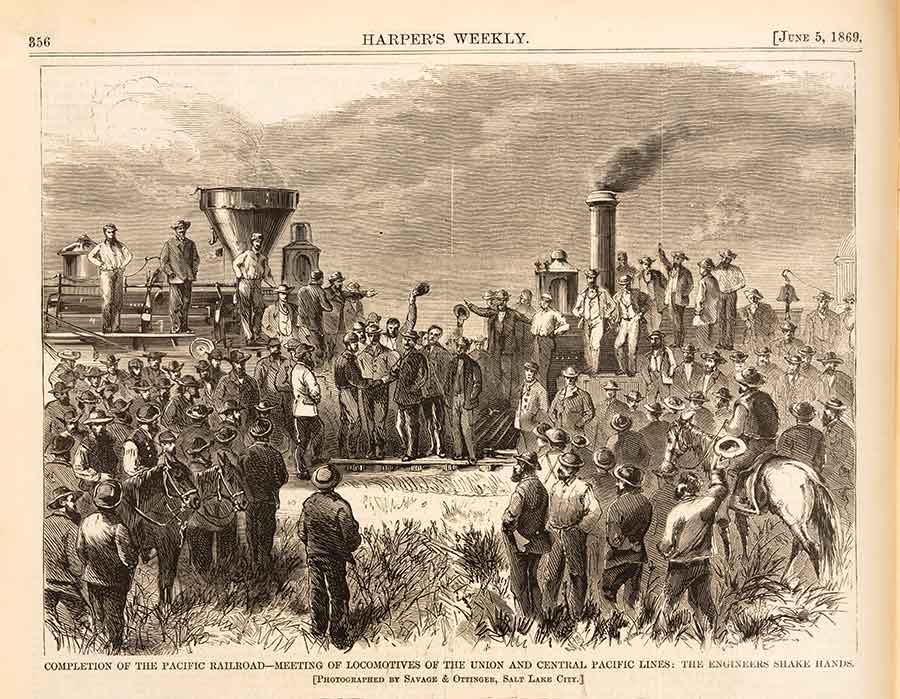

Harper’s Weekly, America’s leading illustrated periodical, celebrated the 1869 joining of the rails with this engraving reproduced from an original photograph. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

It has been 150 years since eastbound and westbound railroad tracks first met at Utah's Promontory Summit, the culmination of many years of planning and hard labor to span the continent with the most advanced transportation technology of its day.

The notion of a transcontinental railroad ignited the imagination of many Americans decades earlier, garnering increasingly serious public support during the 1840s and 1850s. The idea became embedded in the ongoing national debate about the young republic’s destiny. Expressing their support in newspapers, in state legislatures, and on the floor of the United States Congress, proponents offered competing plans to bring the vision to life using both public and private means.

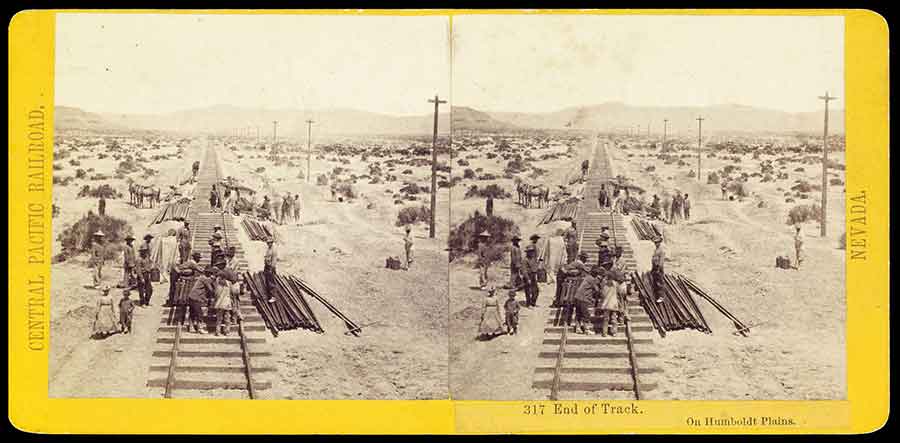

Chinese work crews provided the indispensable muscle for the backbreaking labor of building the Central Pacific Railroad, as seen in this stereograph by A. A. Hart. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In time, under the direction of the U. S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers, parties of explorers, surveyors, and engineers headed west in search of feasible routes for the “iron horse.” During these same years, opponents also found their voices. Some Americans objected resolutely to government sponsorship of the enterprise, while others expressed unyielding hostility to any project that would not benefit their city or state or region. Eventually the project grew entangled with the poisonous national crisis over the expansion of slavery into new territories, becoming another bone of contention in the sectional controversy that convulsed antebellum America. Only after the election of 1860, when Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party dominated a Union diminished by the secession of the Southern states, could a transcontinental railroad at last take shape.

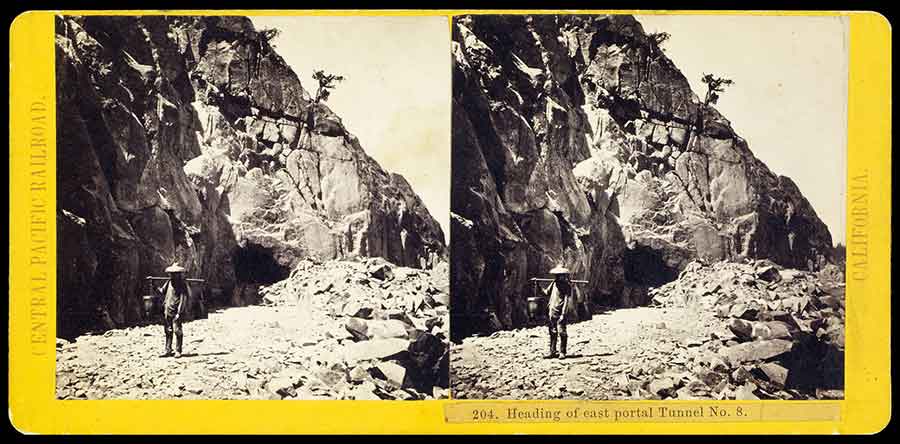

This A. A. Hart stereograph captures the staggering terrain that confronted the Central Pacific’s Chinese laborers who bored through the Sierra Nevada. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1862, Congress pledged substantial government help in funding a transcontinental railroad with the Pacific Railroad Act. The Act promised government bonds and grants of public lands to the federally chartered Union Pacific Railroad and its peer, the Central Pacific Railroad of California. In its wake, various entrepreneurs such as the quartet of Sacramento merchants known as “the Big Four”—Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis P. Huntington (uncle of The Huntington’s founder, Henry E. Huntington), and Leland Stanford—as well as New York railroad financier Thomas C. Durant and Iowa congressman Samuel R. Curtis, pondered how to profit from this endeavor. Even with the promise of federal largesse extended by the 1862 Act, both the Central Pacific and Union Pacific struggled to raise enough money. Neither company, however, could overcome the dire shortages of men, materials, and money at the height of the Civil War. Their failure to make noteworthy progress on the railroad in these early years encouraged their opponents and eroded their financial and political backing.

A stereograph by A. A. Hart of the Central Pacific Railroad’s first locomotive, named after the company’s president, Leland Stanford. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As the American Civil War wound to a close in the spring of 1865, neither the Central Pacific nor the Union Pacific had covered much distance. The Central Pacific, pushing east from Sacramento, California, assaulted the stubborn granite heights of the Sierra Nevada peaks with a growing army of Chinese laborers, hammering out its route mile by mile. Eventually, more than 15,000 workers, many brought by labor contractors directly from China, carved out a track for the Central Pacific’s rails through the Golden State’s towering mountains and across Nevada’s desolate Great Basin. Meanwhile, as the Union Pacific thrust onto the Great Plains, thousands of other men, including multitudes of Civil War veterans from North and South, drove west toward the designated meeting point in Utah Territory. Struggling against ferocious winter storms and stifling summer heat, and stretching their strength and endurance to the maximum, each line’s construction crews increased the pace of their progress despite the unrelenting challenges of terrain and climate. The last spike was hammered in place at Utah’s Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869.

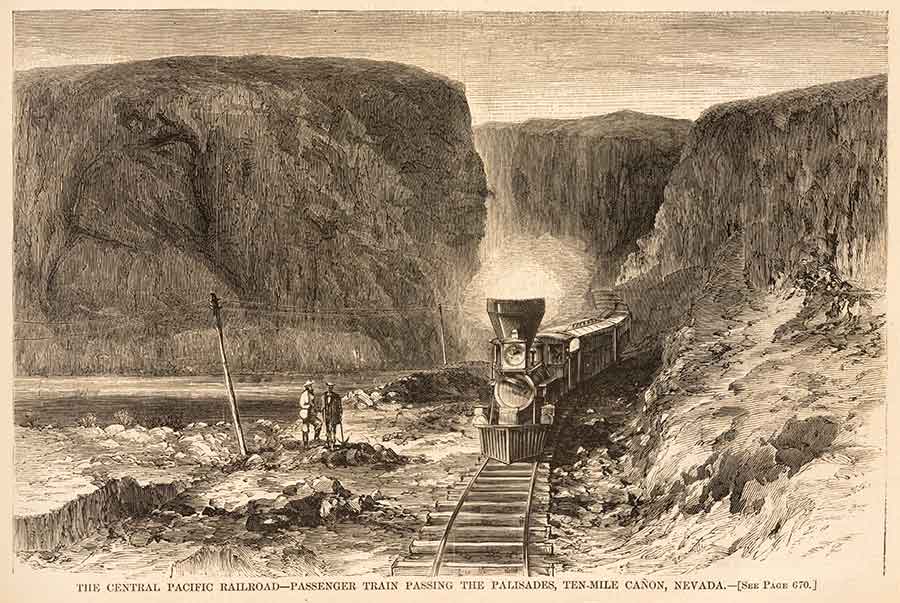

Progress in its construction brought the Central Pacific through the desolate reaches of northeastern Nevada’s Ten-Mile Canyon, as seen in this Harper’s Weekly engraving. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Long before that date, the first locomotives had begun chugging up the slopes of the Sierra Nevada and across the Nebraska prairies. They unleashed irrevocable changes in American social, political, and economic circumstances even as they provoked implacable resistance from indigenous peoples of the plains, such as the Sioux and the Cheyenne, who quickly grasped the threat to their way of life that these changes would cause. The joining of the rails in 1869 accelerated the pace of such transformation, encouraging other entrepreneurs to launch additional transcontinental lines and establishing railroads in many arenas of national life. Investors small and large followed the rails to discover and exploit the diverse and plentiful natural resources of the West. By making large swaths of western landscapes more accessible, for example, the first transcontinental route and the accompanying network of feeder lines facilitated commerce, emigration, and leisure travel, while also allowing the American government to maximize the military and economic advantages of an industrial society against the Native Americans of the Far West.

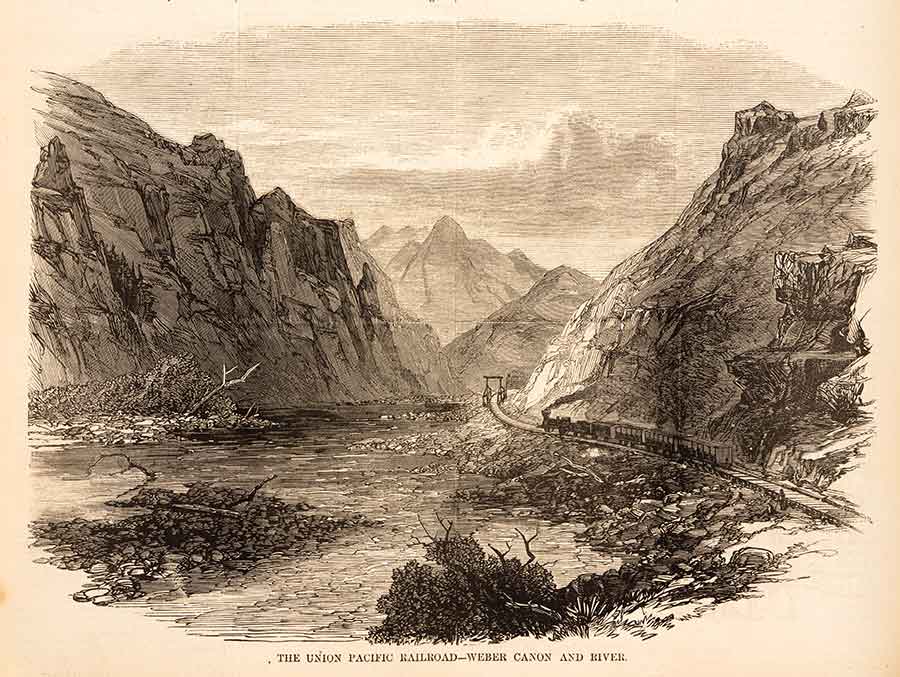

As construction of the Union Pacific’s route approached Utah Territory, the railroad’s workers battled the peaks and canyons of the Wasatch Mountains on their way to Promontory Summit, as seen in this Harper’s Weekly engraving. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

By the early 1880s, the vision of a nation bound together from sea to sea had surely been realized. Three more transcontinental railways had been built by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, the Northern Pacific, and the Chicago and North Western. Determined to profit from their labors, they jostled with each other and with their predecessors, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, for the patronage of farmers, ranchers, immigrants, manufacturers, and tourists. To realize their potential, however, these railroads had to expend great effort to remake the western landscapes. They brought in professional surveyors to map the land and locate the routes, engineers to design the projects, and finally armies of laborers to lay the track, raise the bridges, erect the trestles, dig the tunnels, and build the stations that constituted each railroad’s right of way.

None of these achievements, though, could dispel the anger and disdain many Americans felt for these grand corporate enterprises. Hostile observers argued that the transcontinental railroad had created a new empire, but one ruled by the masters of the iron horse rather than the people. Detractors of the railroads became increasingly vocal, condemning the conduct of individual companies and of the industry as a whole. Many Americans of this era thought of leading railroad men such as Collis P. Huntington and Leland Stanford or the brothers Oliver and Oakes Ames as corrupt speculators, land-hungry corporate buccaneers, or oppressive “robber barons,” caring nothing for the common good. The ensuing struggle between railroads and their critics would echo through the coming century and influence the course of American economic and political life down to our own time.

Peter Blodgett is the H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western American History at The Huntington.