The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Scholar in the Stacks

Posted on Wed., July 24, 2019 by

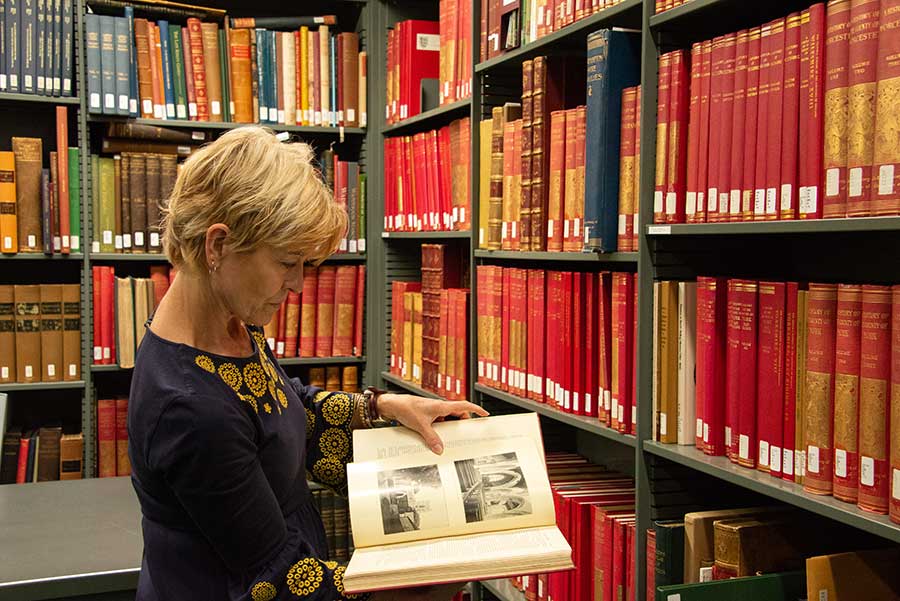

Lori Anne Ferrell, the John D. and Lillian Maguire Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Claremont Graduate University and a 2018–19 Dana and David Dornsife Fellow at The Huntington, leafs through a volume of Victoria County History. Photo by Deborah Miller.

The Huntington Library is one of the world's renowned independent research libraries, housing some 11 million items that span the 11th to 21st centuries. Among these objects are 8 million manuscripts and 440,000 rare books. These are valuable, impressive, and essential. Interrupt any scholar basking over a steaming cup at the Red Car coffee shop to ask why they applied for a reader's card at The Huntington, and (after a guilty glance at their watch) they will most likely say "the manuscripts" or "the rare books." They have, after all, had to declare which of these Huntington treasures they wish to consult in order to get that card.

What they might not mention, however, is this: Whatever it is they seek here, they will undoubtedly be browsing The Huntington “stacks” as well.

Ferrell in the office she used during her 2018–19 fellowship year at The Huntington. Behind her are volumes from the Library’s stacks that were essential for her research. Photo by Deborah Miller.

These “stacks” are the seemingly numberless metal shelves that hold The Huntington’s vast general collection of reference books. These volumes are neither rare nor unique, but necessary for scholarship. These are the workaday books that, generally speaking, complement a scholar’s broader or background research into a topic. The Huntington stacks hold 454,000 reference books, organized according to the Library of Congress Classification System. Among the categories most important for my research are “DA,” which designates books on “British History”; “PR,” which is LC-speak for “English Literature”; and “BR,” which indicates “Church History.” But these are just a few of the hundreds of Library of Congress categories contained in The Huntington stacks—ranging from Art History to California History, from Medieval Drama to Reformation Theology.

Many of the books date from the 1800s. Others were published just last year and still have that new book smell. The stacks will look familiar, then, to anyone who has ever checked out books at a public or university library. But while most university and public library stacks are “open” (meaning: readers can check items out to take home or to their dorm room), The Huntington’s stacks are “closed” (meaning: readers can use them at their desks, but not outside of the Library building complex).

Ferrell searches for a passage in a reference volume. Photo by Deborah Miller.

At The Huntington, the stacks are tucked away: down curving staircases, around the Rothenberg Reading Room’s balcony, and behind large metal doors. Still they are busy places: In the Ahmanson Reading Room, scholars have rare books or manuscripts located, fetched, and delivered by Readers’ Services staff; in the stacks, the readers browse and fetch for themselves.

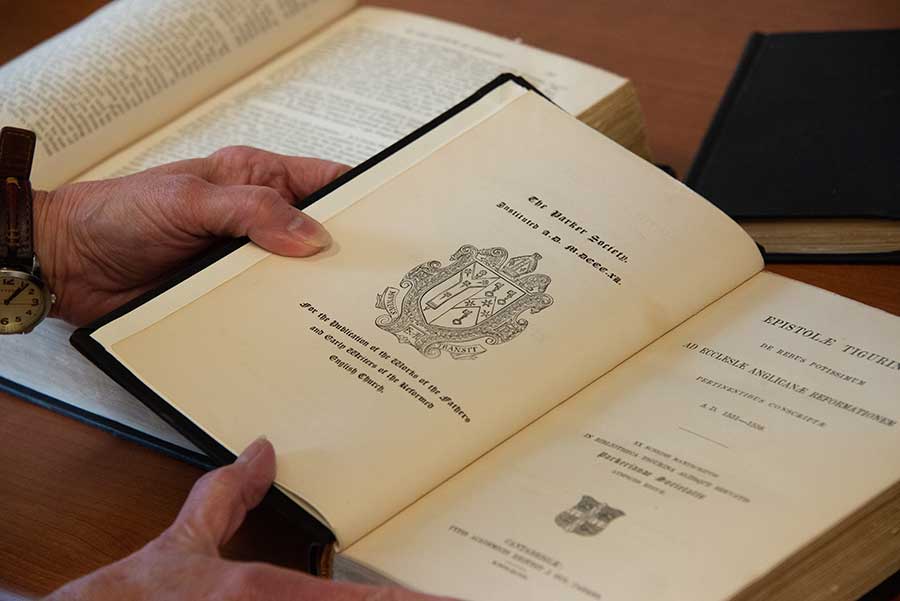

These books are not what have made The Huntington’s library collections famous. But a particular kind of book found in the stacks is the very reason I came on a long-term fellowship to The Huntington this year. I research and write about Victorian-era publication associations. These clubs and agencies underwrote the reprinting of historic books and manuscripts on a massive scale. Many of these historic works can be found in their original form in The Huntington’s rare book and manuscript collections. I am not, however, primarily interested in these historic works as they first appeared, but in the Victorians’ interest in making them newly available in cheap, plentiful reprints. The Huntington stacks hold hundreds of books from these series: works published in the 19th century by local and royal history societies, Protestant subscription associations, and government record offices founded in Britain for this very purpose in that same century. (Many of these associations still operate, and The Huntington acquires new titles annually.) I want to know which works were selected and why, how and by whom they were edited and translated, to what historical purpose these books were put, and who paid the publishing costs.

Cross-referencing requires several books and ample desk space. Ferrrell’s Huntington office space during her 2018–19 fellowship year provided her with both. Photo by Deborah Miller.

Why forgo the thrill of handling rare books and manuscripts—the very reason I decided to declare a history major years ago—for the seemingly ordinary experience of pulling a modern book from the stacks? Because such books demonstrate the importance the Victorians placed on history as a realm of ideas open to all readers. Not everyone can access a world-class library to find what rare books and manuscripts have to say. These works were designed to bring the stuff of history to the public. I am immensely grateful for the time I have had to peruse them at The Huntington.

Lori Anne Ferrell (a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society) is the John D. and Lillian Maguire Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Claremont Graduate University and was a 2018–19 Dana and David Dornsife Fellow at The Huntington.