The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Huntington as Futurist

Posted on Fri., Aug. 30, 2019 by

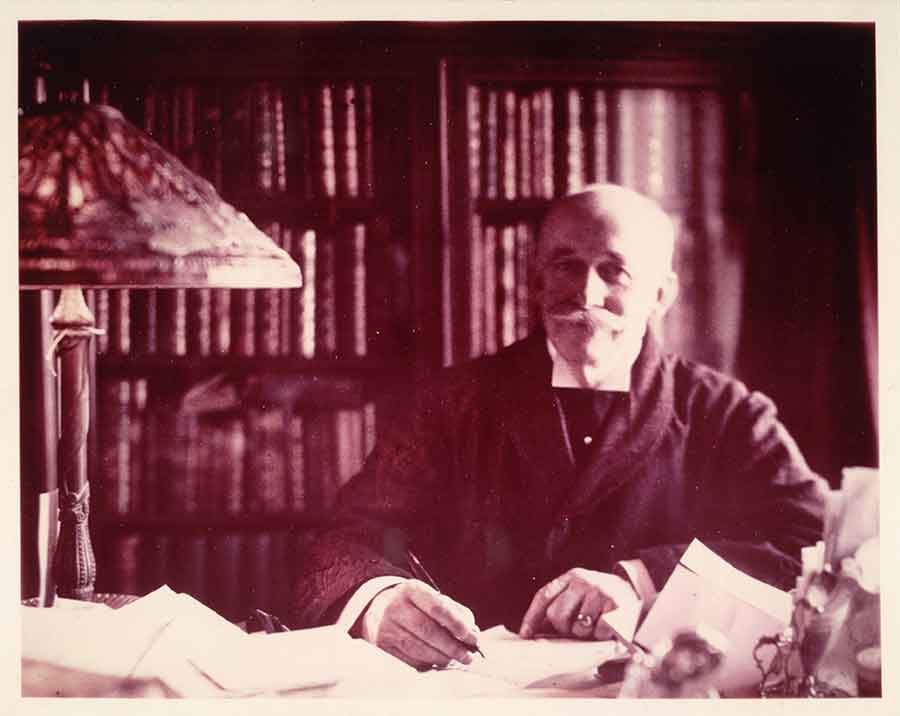

Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927), sitting at his desk. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One hundred years ago today, on a hot, dusty day in San Marino, Henry E. and Arabella Duvall Huntington signed the trust indenture that transformed their private estate into a public institution, setting a course for what this place would become: a historical, literary, art, and botanical wonderland for scholars and the general public.

We are routinely asked: How is it that a place like this exists on the West Coast—a research center with important holdings on the Founding Fathers, British history dating back 10 centuries, and renowned paintings by Thomas Gainsborough, Thomas Lawrence, Edward Hopper, and Mary Cassatt?

The answer? Not by accident.

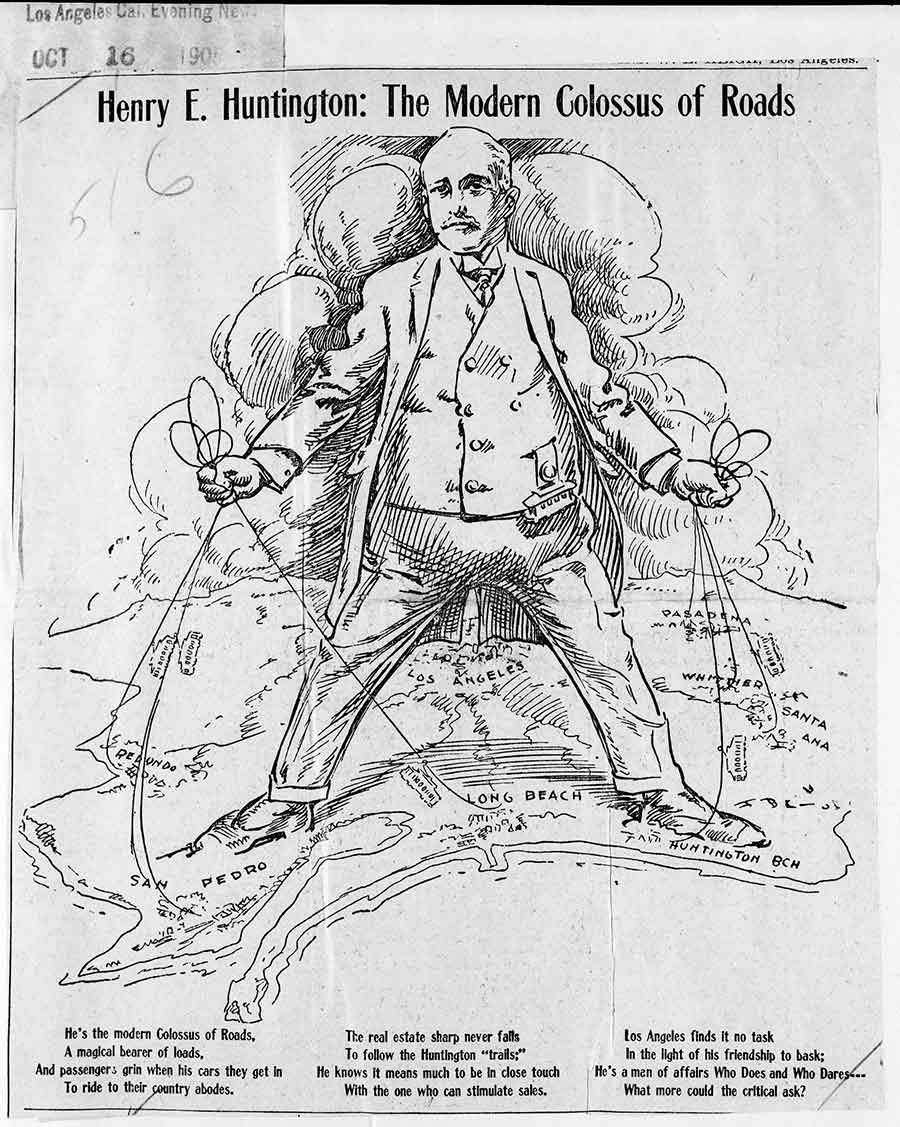

A cartoon of Henry E. Huntington as “The Modern Colossus of Roads,” Los Angeles Evening News, Oct. 16, 1905. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Huntington was something akin to an early-20th-century visionary who may have been taking an even longer view—on into the 21st.

At the turn of the 20th century, having shifted his worldview from New York to parts West, Huntington was about as futuristic a thinker, certainly with respect to Southern California, as one could imagine for his time.

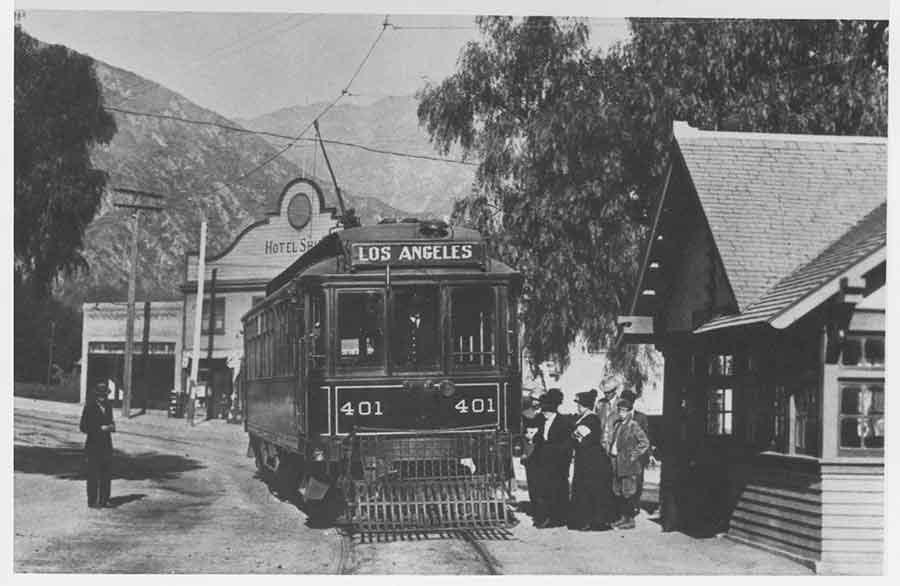

Henry E. Huntington and business associates purchased the Los Angeles Railway, which they then expanded. By 1914, the railway included up to 386 miles of track and had an annual patronage of 140 million passengers. This network, known as the “Yellow Cars,” was dominant downtown. It continued to be held by the Huntington family until 1944. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

He visited Southern California in 1892 and was instantly smitten with the area.

Ten years later, at age 52, he relocated here. In 1902, he wrote, “I don’t think any bright young business fellow can make a mistake in coming to Southern California. Los Angeles is growing very rapidly.” Ultimately, he would come to believe that this world-class city would need a world- class cultural institution, and he aimed to build one. Already a bit of a book collector, he and his wife would—along the lines of other ultra-wealthy titans of their day—avidly compete in the world of high-octane book and art auctions. Ultimately, they assembled the bulk of The Huntington’s collection as we know it today.

When Huntington settled in LA, the population of Los Angeles County was only 170,000. But Huntington arrived with deep experience in building complex businesses and a net worth of $15 million (mostly inherited from his uncle Collis, who, before his death in 1900, had run the nation’s transcontinental railroad empire along with Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker). Huntington saw something in the far-flung landscape of Los Angeles, and it looked like the future.

The trick would be to knit it together.

Sierra Madre Red Line station on Baldwin Avenue, Sierra Madre, California, 1906. The Los Angeles streetcar system totaled 1,140 miles in 1910, which is a third larger than today’s New York City subway system. It was one of the largest privately funded interurban systems ever built. The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California

At the time, electric street railways represented a fairly new technology, and they were highly risky. In LA, the first electric trolley line started in 1887 but went bankrupt by 1893. By 1895, 27 of 28 street railway ventures in LA collapsed. Even so, Huntington saw in it a very profitable future in streetcars. He and his business associates purchased the suffering Los Angeles Railway, which they then expanded relentlessly. By 1914, the railway included 386 miles of track and had an annual patronage of 140 million passengers.

Meanwhile, in 1901, Huntington and his syndicate also formed the Pacific Electric Railway. It was interurban, connecting downtown LA to outlying areas. Huntington went on a massive building and acquisition binge, and by 1910, the mammoth “Red Car” system connected communities in all directions and up to 90 miles away. And here is what he had to say about it all: “I am a foresighted man, and believe Los Angeles is destined to become the most important city in this country, if not the world. It can extend in any direction as far as you like . . . We will join this whole region into one big family.”

Pacific Avenue in Redondo Beach, California, in the first decade of the 20th century, with an electric street car, horse-drawn wagons, and crowds of people in front of a real estate office. Arguably, Huntington’s most successful real estate venture was Redondo Beach. In 1905, Henry bought 90 percent of Redondo. Four days later, he acquired the existing Los Angeles and Redondo Railway, with 57 miles of track, and added it to the Red Car system. Ernest Marquez Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

This was spectacular innovation at the time. The Los Angeles streetcar system was widely acclaimed as the most technologically advanced in the world. Even so, it made no money. But even after his business associates bailed out, Huntington stayed the course. He saw that with the ability to lay track came the ability to create whole communities.

Arguably, Huntington’s most successful real estate venture was Redondo Beach. In 1905, Henry bought 90 percent of Redondo. Four days later, he acquired the existing Los Angeles and Redondo Railway, with 57 miles of track, and added it to the Red Car system.

Henry E. Huntington (seated on the right in the backseat of the closer automobile), inspecting track at Big Creek, California, on April 7, 1914. In 1910, Huntington purchased the water rights to Big Creek, a branch of the south fork of the San Joaquin River in eastern Fresno County, and set about designing the first massively scaled hydroelectric project in the United States. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Huntington built a fabulous spa and plunge pool in Redondo Beach to promote its attractiveness as a destination and real estate investment. And he introduced surfing to California, bringing from Honolulu the dynamic swimmer and surfer George Freeth to help promote the spa and the so-called “largest saltwater plunge in the world.” Freeth was advertised as the “man who walked on water.” The rest is surfing history.

Despite all these successes, Huntington’s biggest capital project still lay ahead. His streetcars required a resource that remained scarce at the turn of the 20th century—electricity. In 1902, Huntington banded with a few associates to form the Pacific Light and Power Company, which quickly gobbled up a number of small local hydroelectric and steam plant facilities.

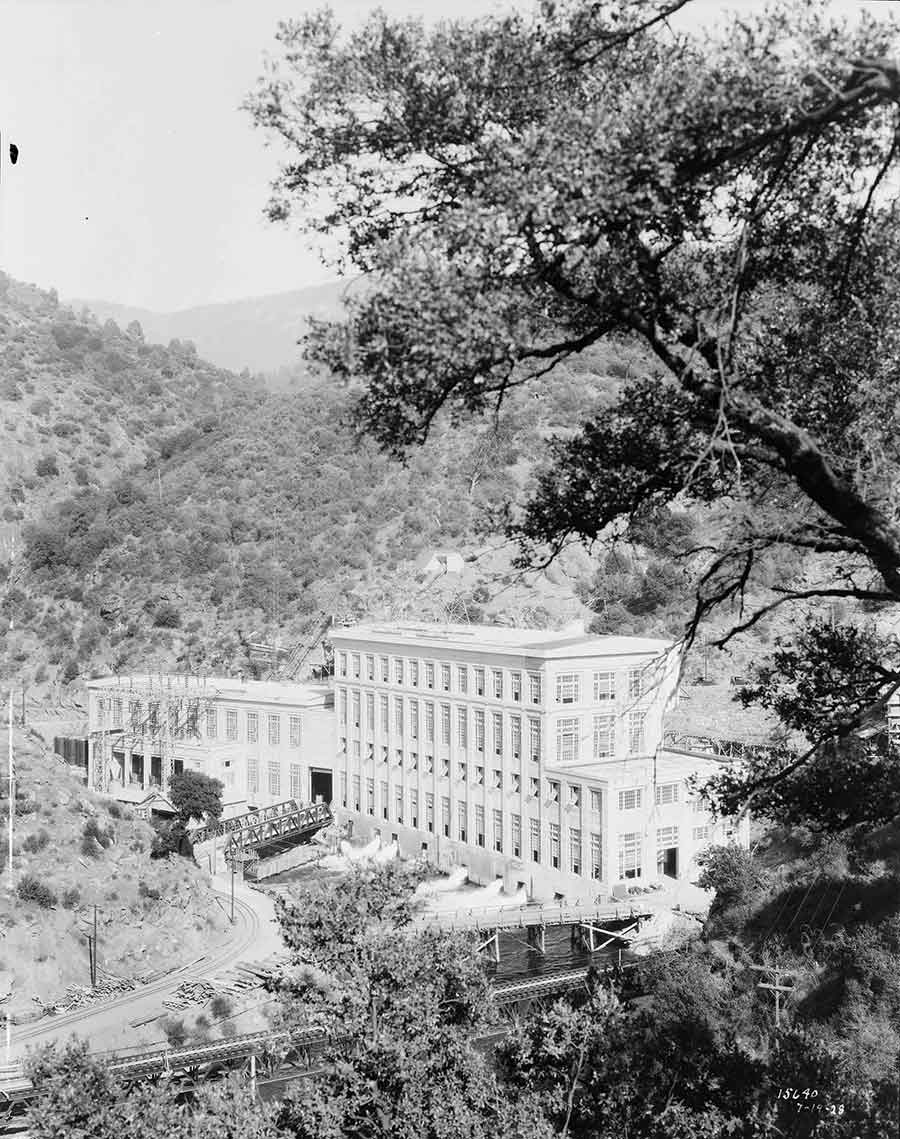

The Big Creek powerhouse, as it appeared on July 19, 1928. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1905, they completed construction of the ambitious 10,000 horsepower hydroelectric plant on the Kern River, one of the largest power-generating projects in the country, and Pacific Light and Power became quite profitable.

In 1910, Huntington purchased the water rights to Big Creek, a branch of the south fork of the San Joaquin River in eastern Fresno County, and set about designing the first massively scaled hydroelectric project in the United States. By 1913, construction was completed on three concrete dams to hold back a large reservoir, known today as Huntington Lake, from which water would descend through pipes to drive two hydroelectric plants in the canyon. Meanwhile, 241 miles of transmission lines to the Eagle Rock substation in northeast LA were constructed.

The John E. Bryson Powerhouse at Big Creek, as it appears today. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1917, as he moved into retirement, Huntington sold his profitable Pacific Light and Power to Southern California Edison. With the acquisition, Edison doubled in size and became the fifth largest central-station power company in the country. Today, Big Creek generates almost four billion kilowatt-hours per year, about 90 percent of Edison’s hydroelectric production.

Even as he focused on supplying the LA basin with electric power, Huntington recognized the parallel demands for water, as well as for natural gas, and began purchasing local water companies. Later, with associates, he formed the Southern California Gas Company.

And so, LA unfolded. And, with it, Huntington’s desire to create that cultural center, amassed from the collections he and Arabella had assembled over the decades. In signing the trust indenture, the couple created an institution that, as described, would exist for “the advancement of learning, the arts and sciences, and to promote the public welfare.” A modest eight-page document put the wheels in motion.

On this day. One hundred years ago.