The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Method to the Madness

Posted on Wed., Aug. 14, 2019 by

Charles Altamont Doyle (British, 1832–1893), The Harvest Home, undated. Pen and watercolor over pencil. Gift of Princess Nina Mdivani Conan Doyle with assistance from The Friends. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

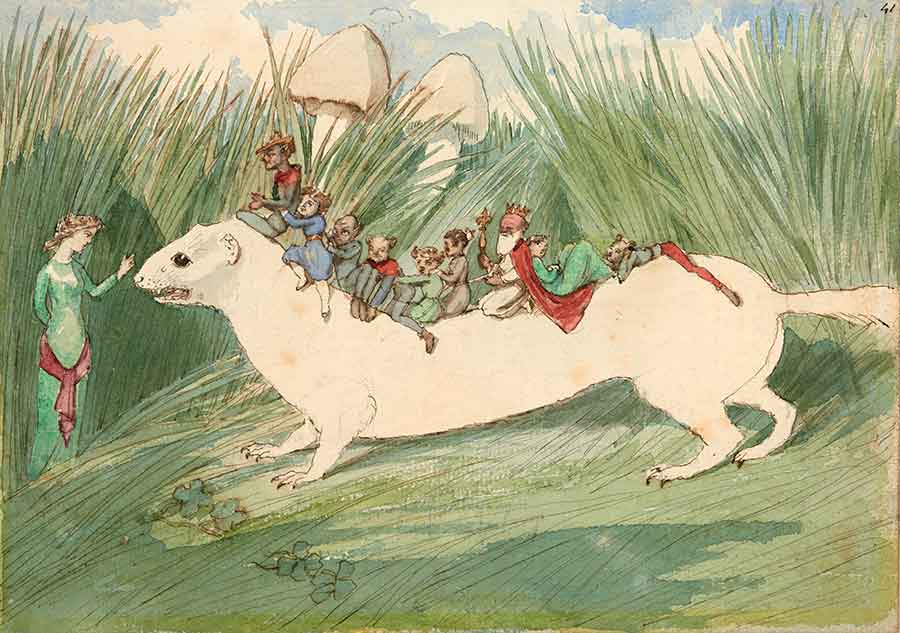

A line of handsome fairy couples dance gaily through sheaths of harvested wheat. Two fairies and their canine companion nestle comfortably beneath an abundance of fuchsia flowers. A brilliantly white ermine with a host of royal elfin riders look ready to leap from the page. All of these fairyland masterpieces (and more) are waiting to enchant you in The Huntington's latest works on paper exhibition, "The Unseen World of Charles Altamont Doyle," currently on view in the Huntington Gallery Works on Paper Room. These imaginative scenes may seem to capture only the nonsensical antics of fairy folk, but if you look closely, there is in fact a method to the madness.

Charles Altamont Doyle (1832–1893) grew up in one of the most artistically inclined families in Victorian London. His father, John Doyle, was a popular caricaturist of the Georgian period, and his older brother, Richard, was a celebrated illustrator for Punch magazine. Charles was a talented artist and illustrator in his own right, but he earned only minor success during his lifetime due in part to his institutionalization for complications related to severe alcohol addiction in 1881, and he remained institutionalized until his death in 1893. Today he is primarily remembered for his connections to his more famous relations, most notably his son Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the world-famous detective Sherlock Holmes.

Charles Altamont Doyle (British, 1832–1893), The Ermine Riders, ca. 1885–91. Pen and watercolor over pencil. Gift of Princess Nina Mdivani Conan Doyle with assistance from The Friends. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The majority of the watercolors and drawings in The Huntington’s exhibition were created while Doyle was a resident of the Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum. For Doyle, painting was not only a way to pass the time, but also a way for him to prove his sanity to his doctors and family. Many have pointed to Doyle’s preoccupation with fairies as evidence of his madness. In fact, Doyle was part of a larger trend of fairy painting in Britain, which began in the 18th century with Romantic artists such as William Blake and Henry Fuseli (whose work features prominently in The Huntington’s collection). The genre’s popularity reached its peak during the middle of the 19th century, just as Doyle was beginning his artistic career. Though rendered in an illustrative style, the fairy revelers in his watercolor The Harvest Home would not have looked out of place frolicking among the works of celebrated Victorian fairy painters John Anster Fitzgerald and Joseph Noel Paton.

Charles Altamont Doyle (British, 1832–1893), The Eavesdroppers, undated. Pen and watercolor over pencil. Gift of Princess Nina Mdivani Conan Doyle with assistance from The Friends. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Fairies not only permeated Victorian painting but also infiltrated Victorian literature. The English language publication of Grimm’s Fairytales in the 1820s sparked a fashion for collections of fairytales, folktales, and legends, which continued well into the 20th century. Both Charles and his brother Richard were avid collectors of obscure fairy stories and superstitions. At first glance, The Ermine Riders looks like yet another whimsical scene of fairy antics, but to those knowledgeable of Irish superstitions, this curious scene makes perfect sense. In Irish folklore, it is terribly bad luck to meet an ermine at the beginning of a long journey. To prevent misfortune, you must greet the ermine as a neighbor. The ermine is also closely associated with royalty, making it a fitting conveyance for the king of the fairies and his retinue.

In addition to exploring folkloric themes, Doyle also used fairyland to express personal sentiments. In his work The Eavesdroppers, Doyle takes the reconciliation of Oberon and Titania, a popular episode from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and uses it to realize his own longings and desires. Look closely at the elegantly bearded man. He is none other than Charles Doyle himself! Cast in the role of the fairy king, he walks through a field of golden wheat with his wife Mary, their fairy subjects trailing behind them. Charles was deeply affected by his separation from his wife during his 13 years in an asylum. His work made it possible for them to be reunited, if only on the page.

Charles Altamont Doyle (British 1832–1893), Considering these are Affuchsias, There are Many of Them, ca. 1885–91. Pen and watercolor over pencil. Gift of Princess Nina Mdivani Conan Doyle with assistance from The Friends. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Doyle not only followed in his family’s artistic footsteps, but also inherited the familial funny bone. His father, John Doyle, was a political caricaturist best known for his refined genteel humor, and his brother Richard’s farcical illustrations graced the pages of London’s leading satirical magazine, Punch. Charles’ own particular brand of humor features prominently in the work Considering these are Affuchsias, There are Many of them. Evident from the abundance of white and red flowers, it is laughably obvious that Doyle has painted more than “affuchsias” (i.e. “a few fuchsias”). Doyle’s fantastically terrible pun is a prime example of the humor prevalent in Victorian popular culture, which was full of witty wordplay and double meanings.

Doyle’s imaginative scenes of fairyland have the power to dazzle and delight just as much as they puzzle and confuse. See if you can uncover the method to the madness yourself!

“The Unseen World of Charles Altamont Doyle” remains on view until September 23, 2019.

Allie Brandt is the guest curator of “The Unseen World of Charles Altamont Doyle.”