The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Feast of the Thousand Old Men

Posted on Wed., Sept. 25, 2019 by

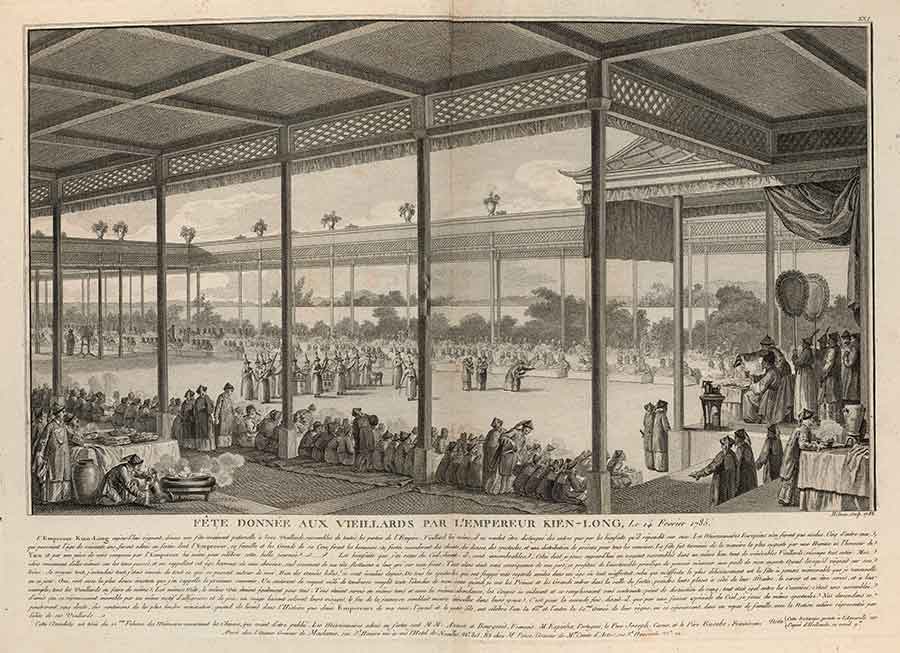

Illustration of The Feast of the Thousand Old Men, or Qiansouyan 千叟宴, held by the Qianlong Emperor in Beijing, 1785. Abrégé historique des principaux traits de la vie de Confucius . . . ornée de 24 estampes in 4°. gravées par Helman, d'apres des desseins originaux de la Chine envoyés à Paris par M. Amiot missionnaire à Pekin . . . . The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

"The Qianlong emperor, now regnant, gave a truly paternal feast for 3,000 old men assembled from all parts of the empire." So reads a first-hand description of the great celebration held in Beijing on February 14, 1785, penned by one of the aged honorees: the 67-year-old French missionary Joseph-Marie Amiot. The Feast of the Thousand Old Men, or Qiansouyan 千叟宴, is a fascinating event in the history of early Sino-Western relations, bringing together two great figures of the global Enlightenment.

Amiot was born in Toulon in 1718 and died in Beijing in 1793. For 40 years, he lived at the North Church, just down the street from the Forbidden City. Ever since the 17th century, a handful of European missionaries had been granted special permission to reside there, working for the Ming and Qing court as astronomers, mathematicians, artists, and technicians. Amiot quickly became fluent in Chinese and Manchu, earning him a part-time job as an interpreter attached to the Grand Secretariat. Meanwhile, he also completed the first Western-language translation of Sun Tzu’s Art of War and won the admiration of such luminaries as Voltaire. By the end of his life, Amiot was the French Enlightenment’s premier authority on China.

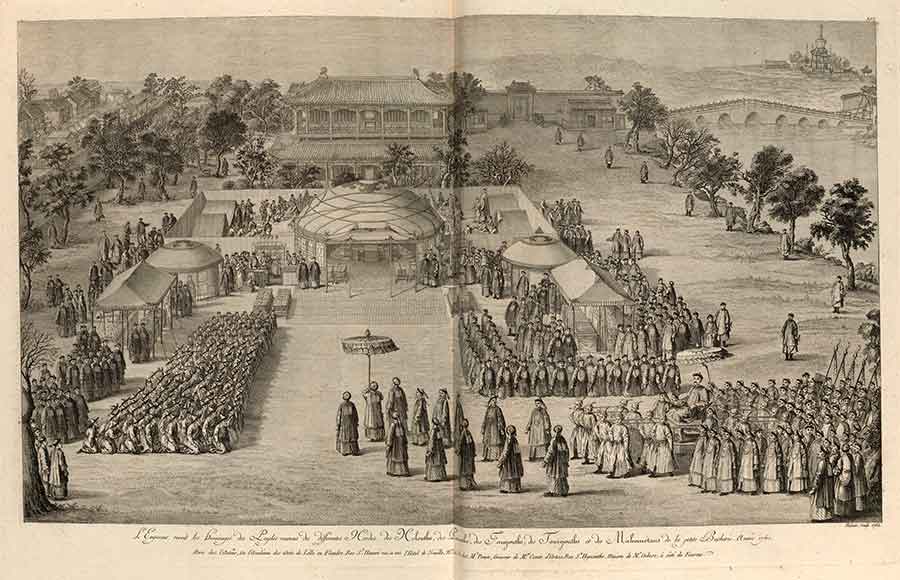

IIllustration of the Qianlong emperor receiving tribute. Abrégé historique des principaux traits de la vie de Confucius . . . ornée de 24 estampes in 4°. gravées par Helman, d'apres des desseins originaux de la Chine envoyés à Paris par M. Amiot missionnaire à Pekin . . . . The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Most of the evidence we have about missionaries’ lives in Beijing comes from the letters they sent back to Europe—and this scarcity is what makes the Feast of the Thousand Old Men so interesting. Unlike for some of his Jesuit predecessors, almost none of Amiot’s Chinese writing survives. Unfortunately for historians, he ordered in his will that all his personal papers be burnt. The only trace that I was able to find was a single short poem in an edited collection, Imperially commissioned poems from the feast of the thousand old men (欽定千叟宴詩). The poem is a unique window into how Amiot saw himself:

Pharos Island, the Colossus, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon; from far away I recall the seven wonders, transmitting the ways of my country and reverentially wishing a long life to the Heavenly Emperor.” (法羅海島銅人像,巴必鸞城公樂場,遠志七奇傳國俗,䖍依萬壽祝天皇)

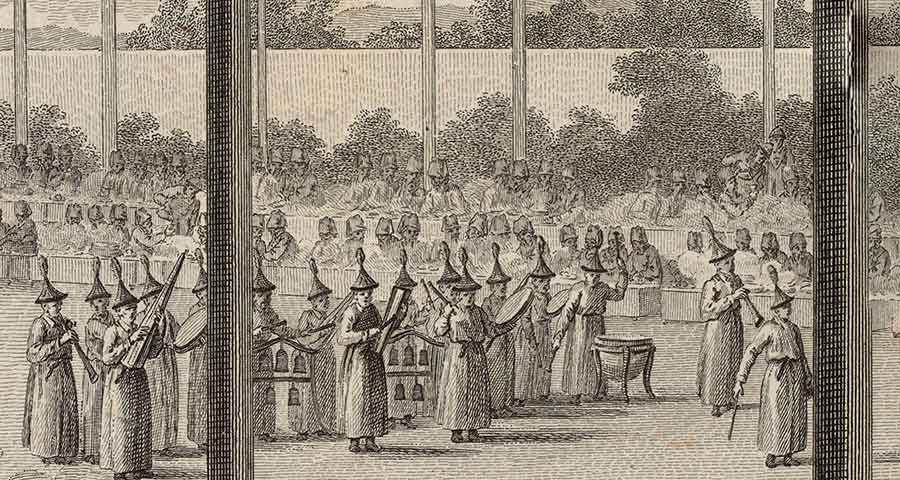

Detail showing musicians at The Feast of the Thousand Old Men, or Qiansouyan 千叟宴, held by the Qianlong Emperor in Beijing, 1785. Abrégé historique des principaux traits de la vie de Confucius . . . ornée de 24 estampes in 4°. gravées par Helman, d'apres des desseins originaux de la Chine envoyés à Paris par M. Amiot missionnaire à Pekin . . . . The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Feast of the Thousand Old Men had inspired Amiot to fully confront his dual identity as both cultural intermediary and imperial servant. So, when I unexpectedly came across a stunning depiction of the occasion in a book at The Huntington—engraved in Paris by Isidore-Stanislas Helman and based on a contemporary illustration made in Beijing—I finally could envision what the feast might have looked like.

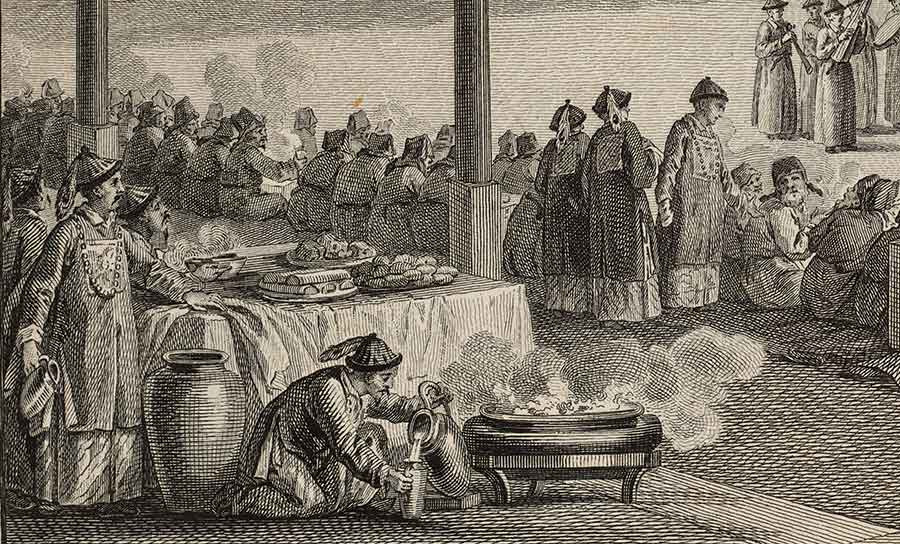

Detail showing a feast table at The Feast of the Thousand Old Men, or Qiansouyan 千叟宴, held by the Qianlong Emperor in Beijing, 1785. Abrégé historique des principaux traits de la vie de Confucius . . . ornée de 24 estampes in 4°. gravées par Helman, d'apres des desseins originaux de la Chine envoyés à Paris par M. Amiot missionnaire à Pekin . . . . The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Amiot described the lavish party as he himself experienced it. At two o’clock in the morning, 3,000 guests—all over 60 years old—arrived at the gates of the Forbidden City, allowing plenty of time to beat the sunrise. After a long procession, the guests sat down to a great feast. Each table was set with a quarter of Mongolian lamb on a hot plate nested among other meats so exotic that Amiot did not even know what animals they had come from. When the emperor’s eldest son personally exhorted him to eat and drink, he had no choice but to oblige. The meal was followed by music, dancing, and a comedy show. Finally, presents were exchanged, and everyone went home exhausted. In virtue of his attendance, Amiot was granted the title of fifth-rank official—the only formal title Amiot ever held in China, and that bestowed for the sole merit of being old.

Alexander Statman was a 2018–19 Dibner Fellow in the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington.