The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Sincerely Yours, Wallace Stevens

Posted on Wed., Sept. 18, 2019 by and

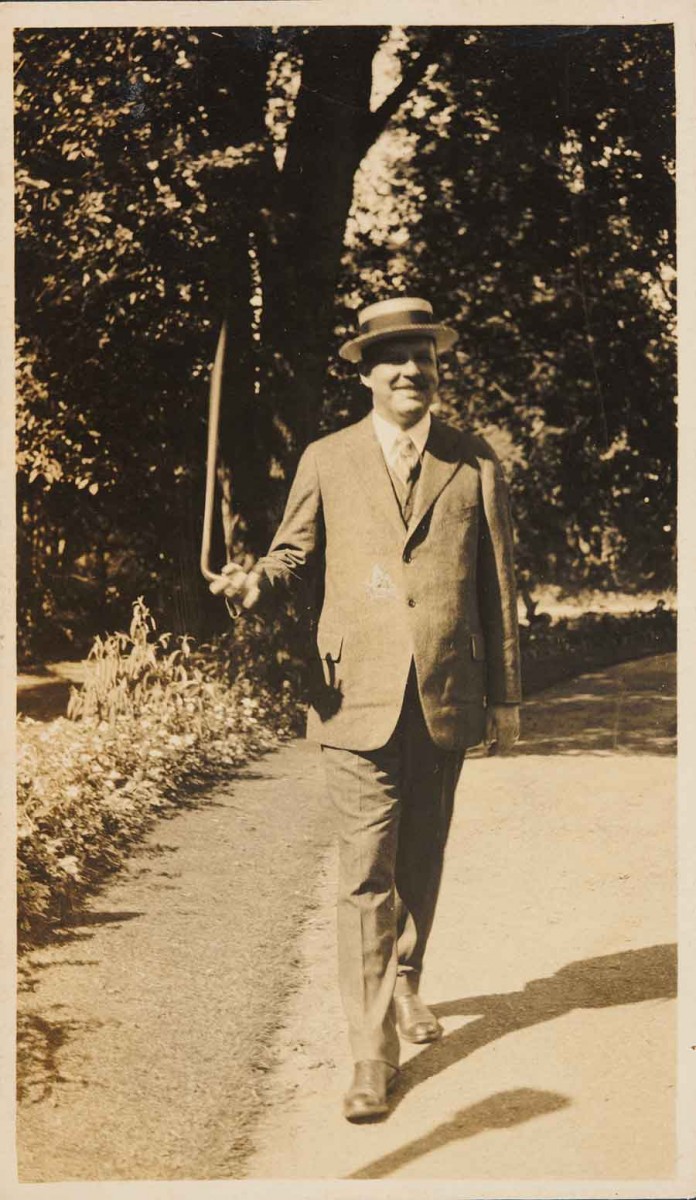

Photograph of Wallace Stevens twirling a cane, circa 1922, Wallace Stevens papers. Unknown photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Especially among poets, artists, and scholars, Wallace Stevens stands as one of the giants of American poetry. His writing is so full of aesthetic and intellectual surprises that, nearly 65 years after his death, experts continue to pore over it. The Wallace Stevens Society drives much of this critical activity by organizing panels, seminars, and conferences on a regular basis. It has also been publishing The Wallace Stevens Journal without interruption for 43 years—longer than any other journal devoted to a 20th-century poet. On The Huntington's behalf, the Wallace Stevens Society has convened a conference titled "Sincerely Yours, Wallace Stevens." Under this heading, we have invited an exquisite group of current and former editorial board members of The Wallace Stevens Journal for a gathering at The Huntington, which will take place on September 20 and 21 in Rothenberg Hall. The purpose is to study Stevens's letters for the first time as a major part of his literary heritage.

Stevens did not socialize easily and was more comfortable corresponding with people than engaging with them face to face. During the years when he wrote most of his poetry, moreover, he was an older man who stuck to his daily routines in Hartford, Connecticut. He did not get around a lot and, as an insurance lawyer in a big company, enjoyed the practical perk of a secretary to whom he could dictate his letters. Growing up, he had wanted to travel internationally, but nothing ever came of these plans.

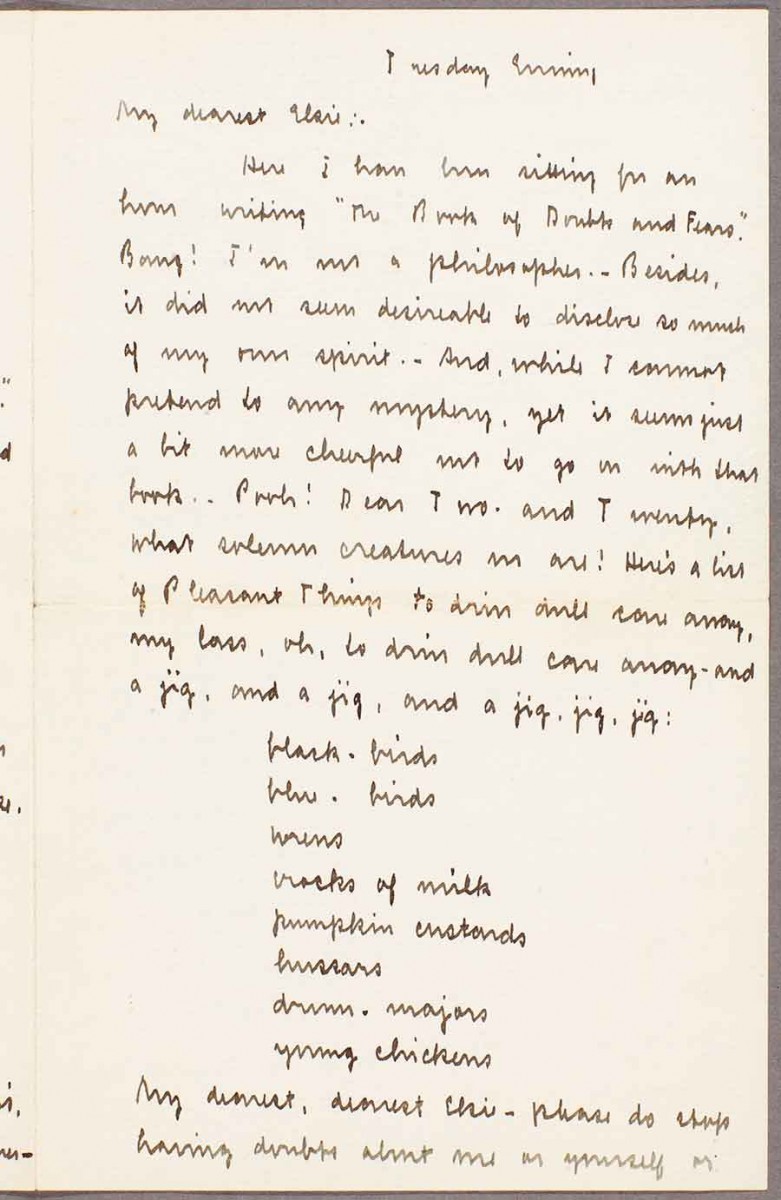

Wallace Stevens letter to his fiancée, Elsie Viola Kachel, Dec. 8–9, 1908, Wallace Stevens papers. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In his imagination, nevertheless, Stevens was a globetrotter all his life; he famously noted that to him life was a matter of places. He came to enjoy dreamed-up visits around the world through a large network of correspondents, with whom he could be verbally and imaginatively playful. He also welcomed opportunities to explain his frequently difficult poetry in letters, though he usually wanted comments to be off the record and was elliptical and enigmatic in his responses. One thing he dreaded was the possibility that readers would stop reading a previously alluring poem because they felt they knew the answer to it. To Stevens, poems should remain so appealing that you want to return to them over and over again.

Stevens’s comments about his own work have become a basic staple of criticism. When Letters of Wallace Stevens was reissued as a paperback in 1996, the poet Richard Howard even exulted that the collection “remain[s] a readily ascended Everest in a landscape of not-to-be-neglected Himalayas” (that is, other poets’ published correspondence). To Howard, the letters “afford the most consistent meditation any poet in any language has ever put in writing on the sense of his work.”

Postcard of the towers of San Gimignano, in Italy, sent to Wallace Stevens by his friend Barbara Church on Sept. 28, 1952. Stevens came to enjoy dreamed-up visits around the world through a large network of correspondents. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The poet’s daughter, Holly, published her nearly 900-page selection of her father’s letters back in 1966. She then sold most of the correspondence (together with her father’s personal library) to The Huntington as part of the Library’s two major Stevens acquisitions in 1975/76 and 1990. Over the years, many scholars have studied these materials individually. Thus, the Wallace Stevens archive at The Huntington played an important role in the historical and biographical shift in Stevens studies that started in the 1980s. In due course, scholars brought out two further book-length collections of letters: Secretaries of the Moon: The Letters of Wallace Stevens and José Rodríguez Feo (1986) and The Contemplated Spouse: The Letters of Wallace Stevens to Elsie (2006).

The literary and biographical importance, stylistic qualities (including the humor!), and intellectual substance of Stevens’s letters are beyond doubt. Yet this conference will be the first occasion when the attention of an entire group of international experts will turn to Stevens as a correspondent. For those who are able to attend this unique gathering, as well as the many others who cannot make it, the good news is that we plan to publish all contributions afterward as two special issues of The Wallace Stevens Journal.

Bart Eeckhout is professor of English and American literature at the University of Antwerp in Belgium and has been editor of The Wallace Stevens Journal since 2011.

Lisa Goldfarb, professor at the Gallatin School for Individualized Study at New York University, is president of The Wallace Stevens Society and associate editor of The Wallace Stevens Journal. Together, Eeckhout and Goldfarb have organized several conferences and edited multiple collections of essays on the poet.