The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In America, Nineteen Nineteen

Posted on Wed., Oct. 16, 2019 by

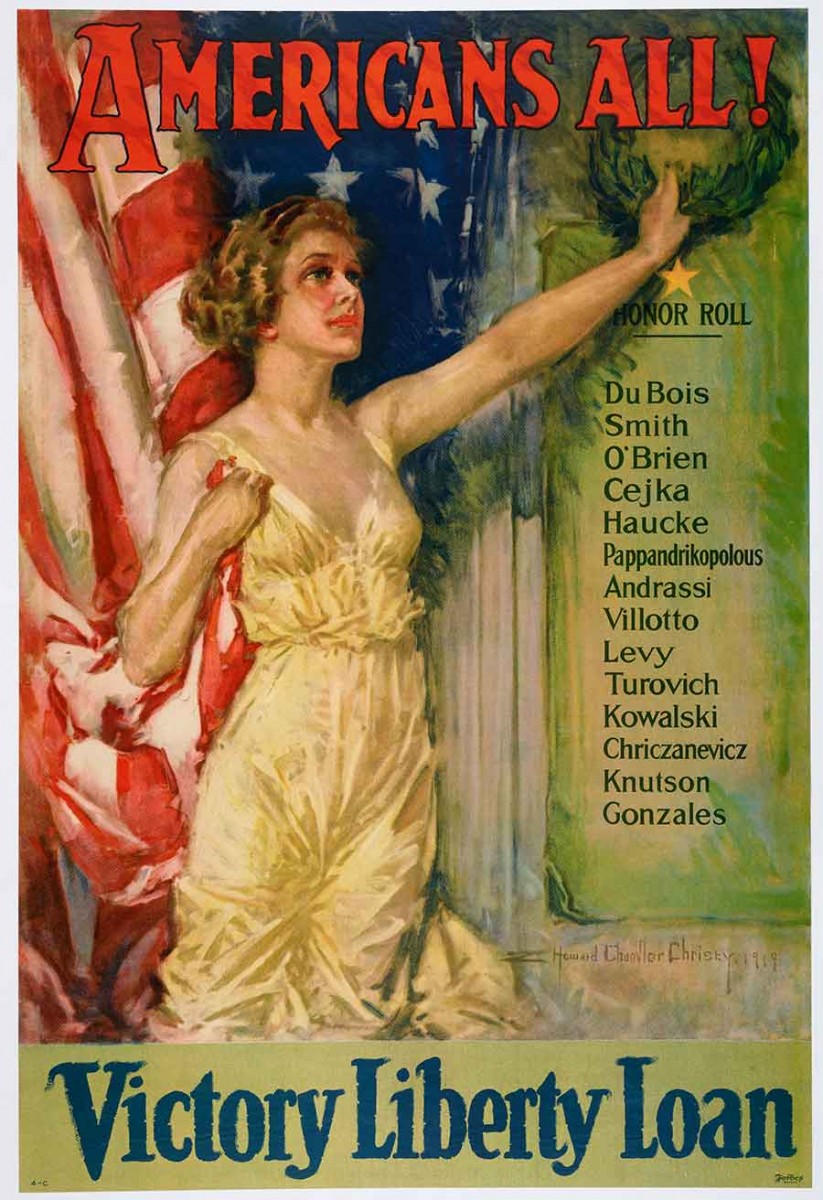

Howard Chandler Christy, Americans All!, 1919, lithograph, 40 x 26 7/8 in., Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing, Boston. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In the summer of 1919, from the pages of the Oakland Tribune, Professor Albert Porta predicted a "terrific weather cataclysm" for December 17—an event that would end the world. The disaster never took place. The year 1919 proved to be cataclysmic nonetheless.

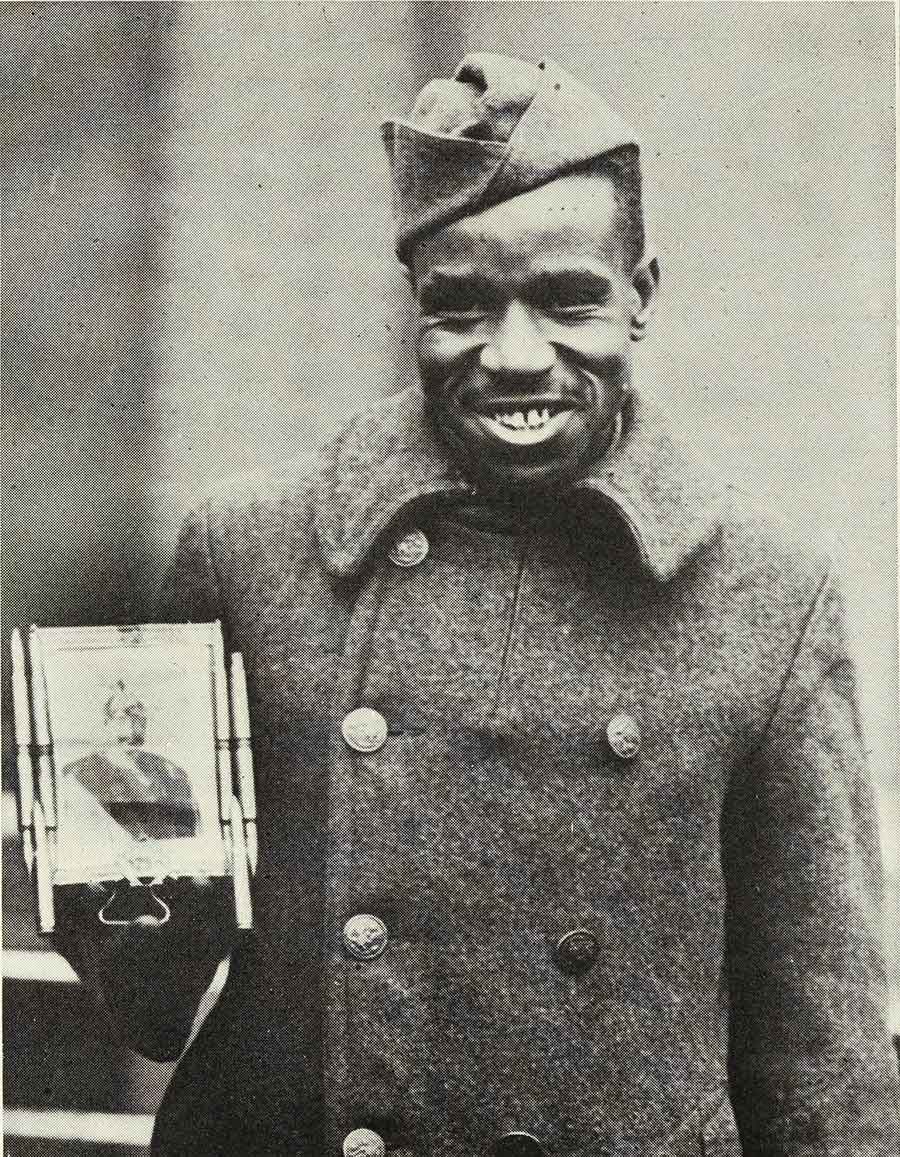

On June 28, 1919, Woodrow Wilson added his signature to the Treaty of Versailles. In the United States, though, the Senate never ratified the treaty, convinced that the League of Nations—Wilson’s vision—would compromise American autonomy. Wilson declared in 1917 that the U.S. entered the war to make the world “safe for democracy,” but throughout America, democracy found itself crippled by nationalist paranoia and racist hysteria. The government raided radical organizations, arrested suspicious individuals, and deported thousands of immigrants, even as the new Victory Loan Program celebrated the diversity of the soldiers who had fought overseas—Americans All! Across the nation, vigilante mobs destroyed black communities and murdered black men and women.

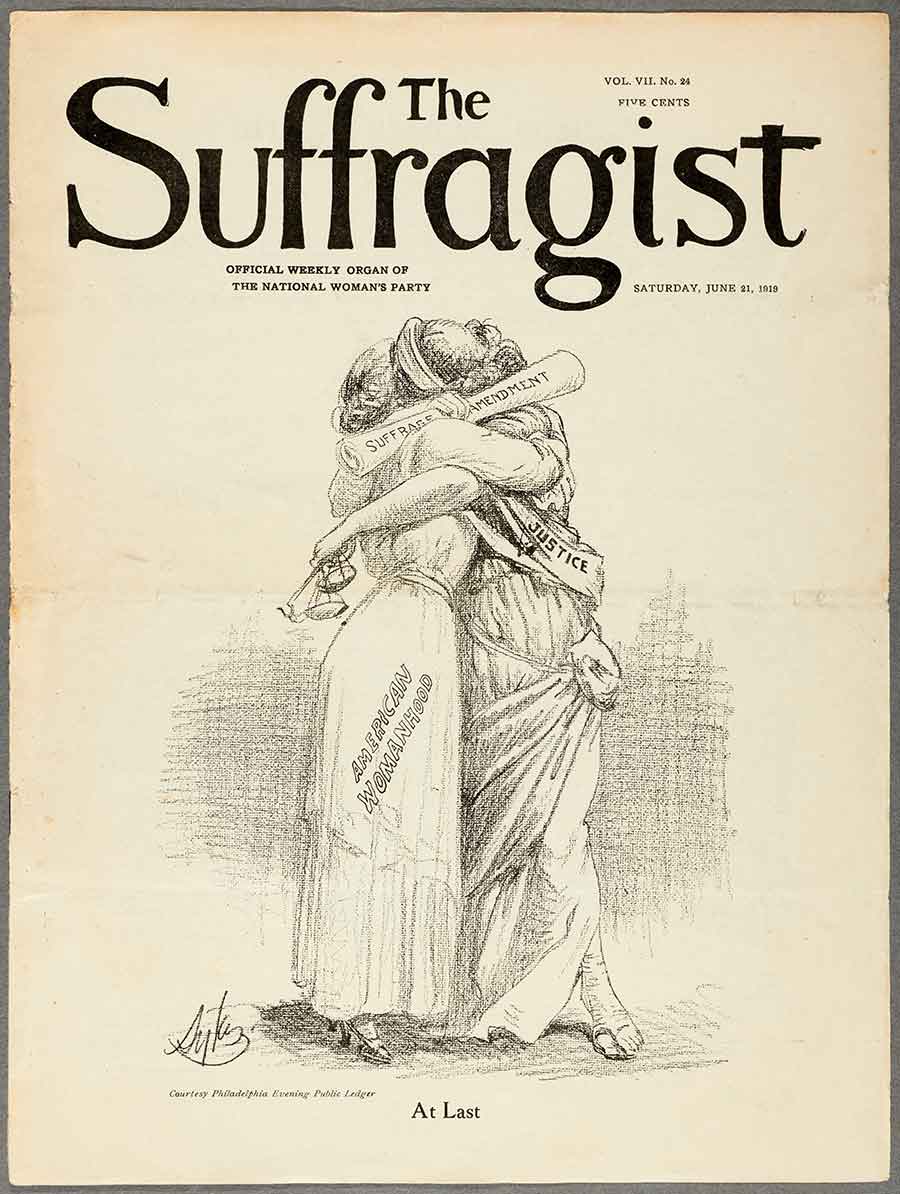

Charles H. Sykes, “At Last,” in The Suffragist, June 21, 1919, National Woman’s Party, Washington, D.C. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

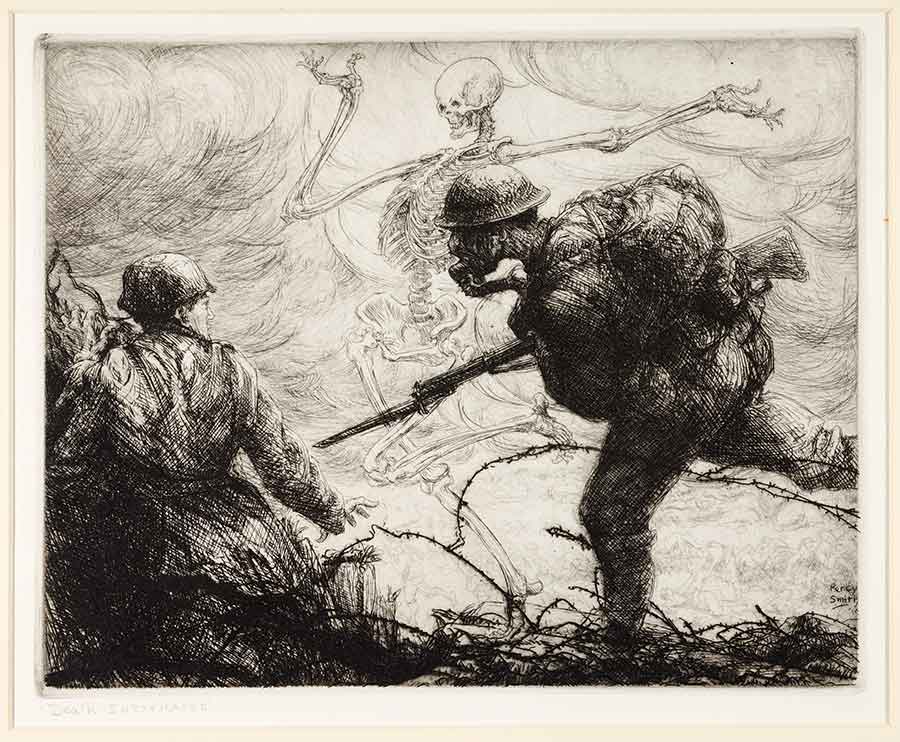

Though the Great War had finally come to an end in Europe, in America new battle lines were drawn, and crossed. The Red Scare, the Red Summer of racial violence, a third wave of the flu pandemic, labor protests—these rocked the country as millions of returning soldiers and volunteers struggled to settle into some new routine. Victory parades filled city streets; so too did riots. Still, it was a year that saw the passionate assertion of political, human, and civil rights. In 1919, the NAACP attracted tens of thousands of new members. And, in June of that year, both houses of Congress finally supported a woman’s right to vote.

In 1919, Henry E. Huntington founded the library, art museum, and botanical garden that bear his name. “In America, Nineteen Nineteen”—a conference designed in conjunction with The Huntington’s “Nineteen Nineteen” exhibition—will focus on cultural, social, and political events—and the afterlives of those events—that provide a national and international context for Huntington’s remarkable act of philanthropy.

“Corporal Fred. McIntyre of the 369th Infantry with Picture of the Kaiser Which He Captured from a German Officer,” in William Allison Sweeney, History of the American Negro in the Great World War, 1919, Cuneo-Henneberry, Chicago. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Eminent scholars from a wide range of disciplines—history, philosophy, art history, African American studies, literature, and film—will shed new light on this year in U.S. history, illuminating facets of American life within, yet beyond, the history of the war’s end and of the enormity of postwar social struggle. What were the origins of Wilsonianism? What was the Caribbean response to the new stature of the U.S.? What was the aesthetic response to war and its aftermath? What novels were Americans reading? What songs were being sung? How did city planning respond to new demographic urgencies? How was the body reconceived in response to health crises? And why, after all, did Professor Porta’s prediction provoke such panic?

Percy John Smith, Death Intoxicated, 1919, etching, charcoal and stump on paper, 10 1/16 x 13 3/16 in., from the series The Dance of Death, 1914–19. Gift of Russel I. Kully. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As part of the conference, curators James Glisson and Jennifer A. Watts will discuss how they developed their exhibition and catalog: how they came to convey the story of 1919 “by mining the millions of documents, objects, paintings, ephemera, photographs, and volumes found in The Huntington’s archives, galleries, and book stacks”; and how they balanced a celebration of Henry Huntington’s philanthropic achievement with the recognition of his status as California’s most aggressive and powerful antiunion business leader. On August 16, 1919, workers on Huntington’s street car railways walked off the job in a strike that soon led to riots. A mere 10 days later, on August 30, Henry and Arabella Huntington signed the trust indenture that created The Huntington, an institution that would "advance learning in the arts and sciences."

In America, 2019, political turmoil is ravaging the nation state. It has also become a retrospective year: a year in which to see how 1919—its infamous events and the ways that individuals grappled with them—continues to shape our present.

You can listen to the conference presentations here.

Bill Brown is the Karla Scherer Distinguished Service Professor in American Culture at the University of Chicago. He teaches in the departments of English and of Visual Arts, and he serves as a coeditor of Critical Inquiry.