The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Right Way to Remember Charles Dickens

Posted on Wed., Oct. 30, 2019 by

Charles Dickens (1812–1870), photographed in 1861 by John Watson. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

I was lucky enough to spend June 2019 as a Michael J. Connell Foundation Fellow at The Huntington, working with the James Thomas Fields Papers, a collection containing more than 5,000 items. James T. Fields (1817–1881) was editor of the Atlantic Monthly and the only American to secure an official agreement with Charles Dickens (1812–1870) to publish his novels in the United States, at a time when copyright and intellectual property were hotly disputed. Dickens was both professionally and personally close with Fields and his wife, the author Annie Adams Fields (1834–1915): Dickens had stayed with them only two years before on his American public reading tour, during which he delivered 423 readings. In The Huntington's collection, there is a letter from Dickens's sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, to Annie Fields, referring to a set of three photographs taken after Dickens's death.

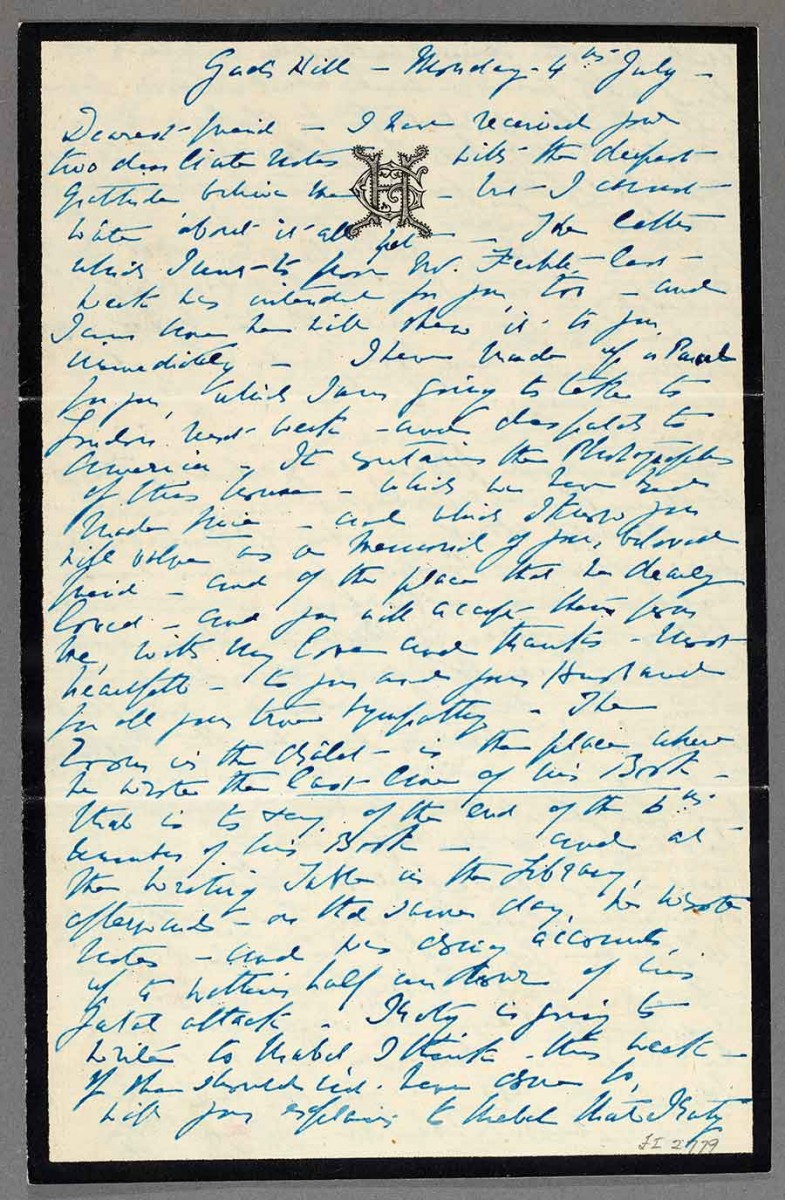

On July 4, 1870, Hogarth wrote:

I have made up a Parcel for you, which I am going to take to London next week and despatch to America—It contains the Photographs of this house—which we have made since—and which I know you will value as a memorial of your beloved friend— and of the place that he dearly loved—and you will accept them from me, with my love and thanks—most heartfelt—to you and your Husband for all your true sympathy—The room in the Châlet—is the place where he wrote the last line of his Book—that is to say, of the end of the 6th Number of his Book—and at the Writing Table in the Library, afterwards—on the same day, he wrote notes—and was doing accounts, up to within half an hour of his fatal attack—

The three photographs, which are also in The Huntington’s collection, were sent early in a friendly correspondence between the two women that would last for nearly 50 years, and they show three different ways of remembering Dickens.

First page of a letter from Georgina Hogarth, sister-in-law of Charles Dickens, to Annie Adams Fields, July 4, 1870. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Dickens and Shakespeare

First, Gad’s Hill itself. Dickens bought the house in 1856 and lived in it, on and off, until his death in 1870, though he took some time making alterations to it and was regularly back and forth to London. His final alteration, finished just days before he died on June 9, 1870, was to add a conservatory to the building.

Gad’s Hill is rooted in its connection to Shakespeare’s character Sir John Falstaff: It is the site of a robbery Falstaff commits in Henry IV, Part 1. Shortly after purchasing the house, Dickens commissioned an inscription that hung by the door as guests entered, highlighting the connection. The house represented Dickens’s position in the literary canon—or, in any case, his aspiration.

Not only did the location have connections to Shakespeare, but it epitomized Dickens’s success and his drastic change in circumstances. In the 1860 article “Travelling Abroad,” Dickens describes meeting himself as a “very queer small boy,” aspiring to one day live in the house:

“Bless you, sir,” said the very queer small boy, “when I was not more than half as old as nine, it used to be a treat for me to be brought to look at it. And now, I am nine, I come by myself to look at it. And ever since I can recollect, my father, seeing me so fond of it, has often said to me, ‘If you were to be very persevering and were to work hard, you might some day come to live in it.’ Though that’s impossible!” said the very queer small boy, drawing a low breath, and now staring at the house out of window with all his might.

Together, these two associations form part of the dominant narrative of Dickens’s life: He was fated to live in Shakespeare’s Gad’s Hill, just as he was fated to be an author, securing his personal and professional legacy.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870) bought this house at Gad’s Hill in 1856 and lived in it, on and off, until his death in 1870. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Man of Letters

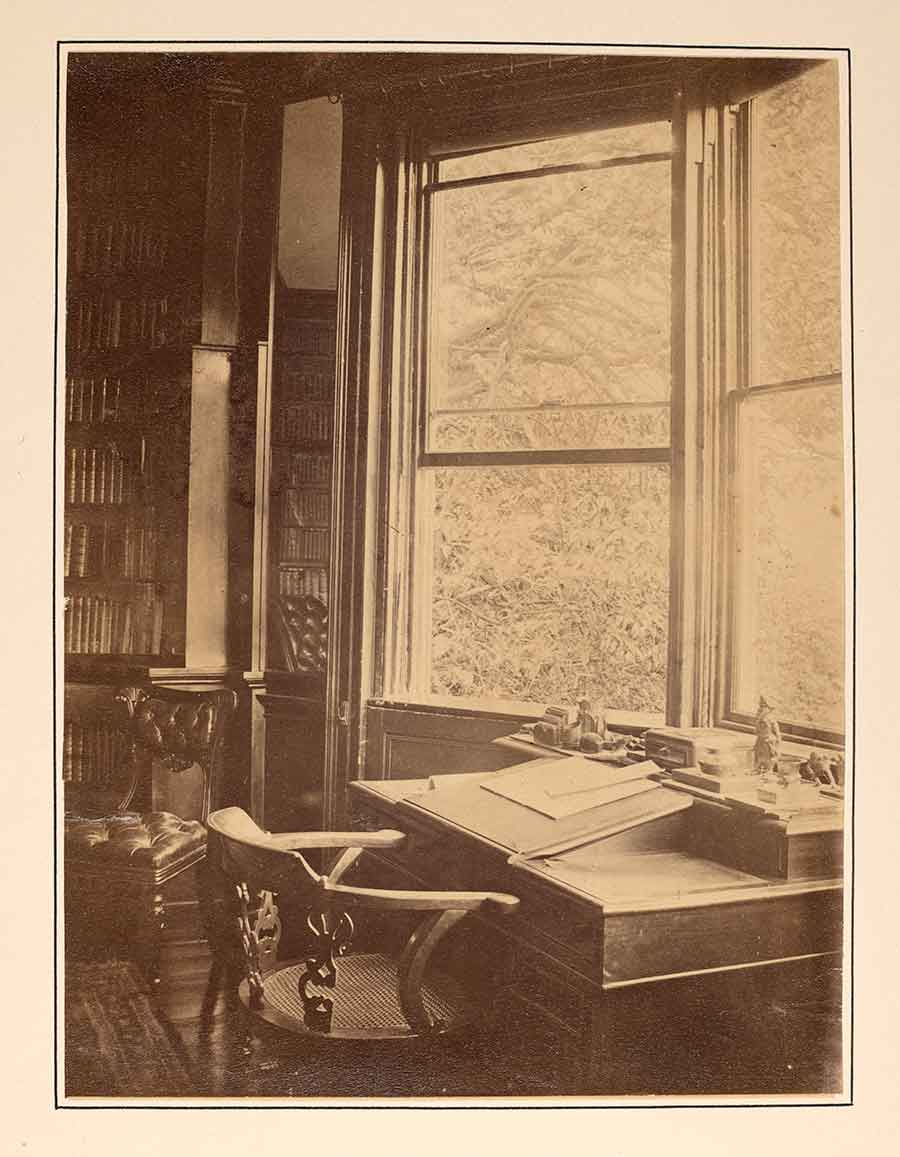

Like Gad’s Hill itself, the study in Dickens’s Gad’s Hill house represents a conventional kind of aspiration for a lower-middle class child haunted by the threat of financial ruin; Dickens’s father had been imprisoned in Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison, and a young Charles sent to work in a boot-blacking warehouse. For a man who felt like he had come from nothing, the study represented a kind of gentility that Dickens had long desired.

The study is central to representations of Victorian authors: a “man of letters” needed to have both the domestic space that the home represents, and also a professional space within it to work. Added to this, the domestic was a key part of Dickens’s self-image: He sought to be a personal friend to his readers, and he prided himself on the intimacy he had with his public in their own homes through their reading of his novels.

However, in My Father As I Recall Him, his daughter Mamie relates being brought into Dickens’s study at an earlier home, Tavistock House, so that her father could keep an eye on her when she was ill:

. . . my father wrote busily and rapidly at his desk, when he suddenly jumped from his chair and rushed to a mirror which hung near, and in which I could see the reflection of some extraordinary facial contortions which he was making. He returned rapidly to his desk, wrote furiously for a few moments, and then went again to the mirror. The facial pantomime was resumed, and then turning toward, but evidently not seeing, me, he began talking rapidly in a low voice . . . he had actually become in action, as in imagination, the creature of his pen.

The description is a powerful one that creates a sense of speed and action, and alienates the father from his awestruck daughter. Dickens seems almost mad, unable to see his own child, and less the lone genius working quietly in his study or the domestic man than an untamed “creature” that is worked upon by forces outside of his control. This kind of anecdote highlights Dickens’s uneasy status as a respectable “man of letters,” not quite embodying the Victorian ideal.

The study in Dickens’s Gad’s Hill house. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

At the Bottom of the Garden

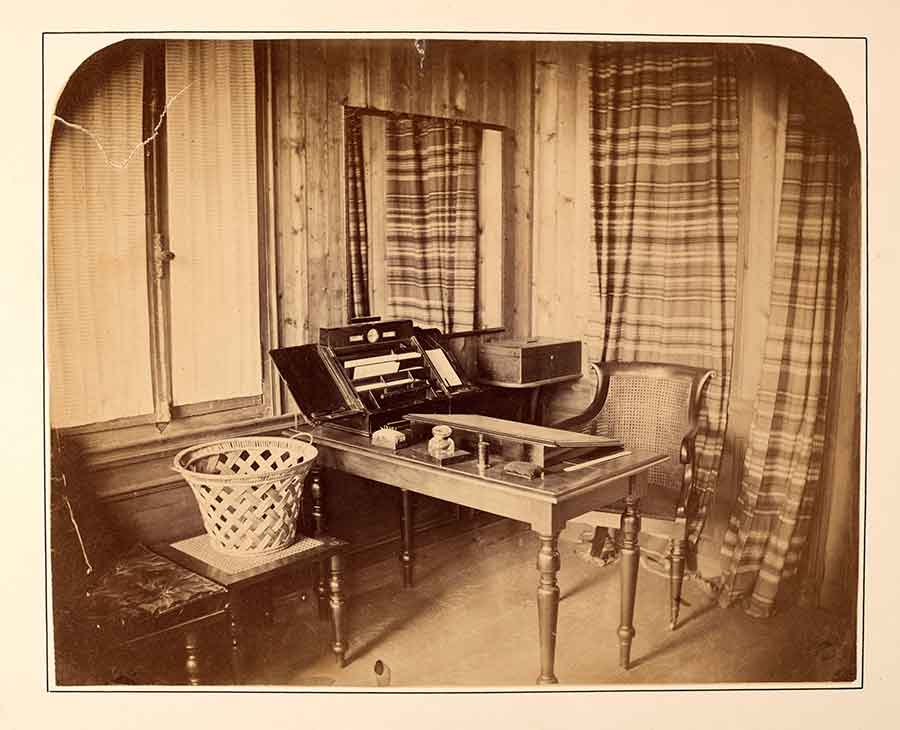

The anecdote from his daughter gestures to the bigger problems of the third picture, which takes Dickens outside of the house entirely. On the day Dickens died, he was not writing the latest installment of his final, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, at the respectable desk in his study. He spent longer than usual writing in his Swiss chalet, a wooden structure with two rooms of about 16 square feet each, ten windows in total and five mirrors in the upper room, given to Dickens by the actor Charles Fechter for Christmas in 1864 (imagine a large Wendy house or garden shed). The chalet was placed across the road from the house, accessible by a tunnel and overshadowed by two large cedar trees. During its complex history, it has been a Dickensian pilgrimage site and (briefly) an attraction on the grounds of the Crystal Palace.

The wooden chalet is a reflective space as well as an isolated one. Within it, surrounded by windows and mirrors, Dickens was alone with reflections of nature—and reflections of himself, the creature of his pen. Its position, not quite outside but also not part of the house, was also problematic. The room in which Dickens did most of his writing for the last years of his life—in warmer weather, at least—was not his impressive Gad’s Hill study but a modest room in his chalet.

The photograph of this chalet room adds to the difficulty of “interpreting” the chalet: in sepia tones, the distinction between the mirrors and the windows, covered in lined curtains, is unclear, and the perspective does not give us a sense of the view from Dickens’s desk in the way the study photograph does. That the mirrors should “reflect and refract truly” was important to him. To Annie Fields, he wrote:

I have put five mirrors in the Swiss châlet (where I write) and they reflect and refract in all kinds of ways the leaves that are quivering at the windows, and the great fields of waving corn, and the sail dotted river. My room is up among the branches of the trees; and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in, at the open windows, and the lights and shadows of the clouds come and go with the rest of the company. The scent of the flowers, and indeed of everything that is growing for miles and miles, is most delicious.

The mirrors around the chalet also allowed Dickens to “perform” his characters, as explained by his daughter Mamie. Significantly, there are no books in the chalet, and only a small chair and stool. And, unlike in his Gad’s Hill study, the desk does not face toward a window but into the room itself, with full view of the mirrors. Once we know that Dickens acted out his characters, this set-up makes sense, but it challenges Dickens’s respectability in Victorian terms.

The room in a chalet where Dickens did most of his writing for the last years of his life. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

These three photographs, sent to friends to commemorate Dickens, offer the receiver a choice: Remember the personal, private Dickens of the chalet; the respectable writer at his masculine-coded desk in the Gad’s Hill study, or the Dickens who aspired to live in the Gad’s Hill house, and eventually achieved that desire. To accept all three is to begin to build up an image of a more three-dimensional person by moving beyond stereotypes, both about Dickens’s life and also about Victorian authorship itself.

Emily Bell is Research Associate in Digital Humanities at Loughborough University.