The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Notes from the Elizabethan Catholic Underground

Posted on Wed., Nov. 6, 2019 by and

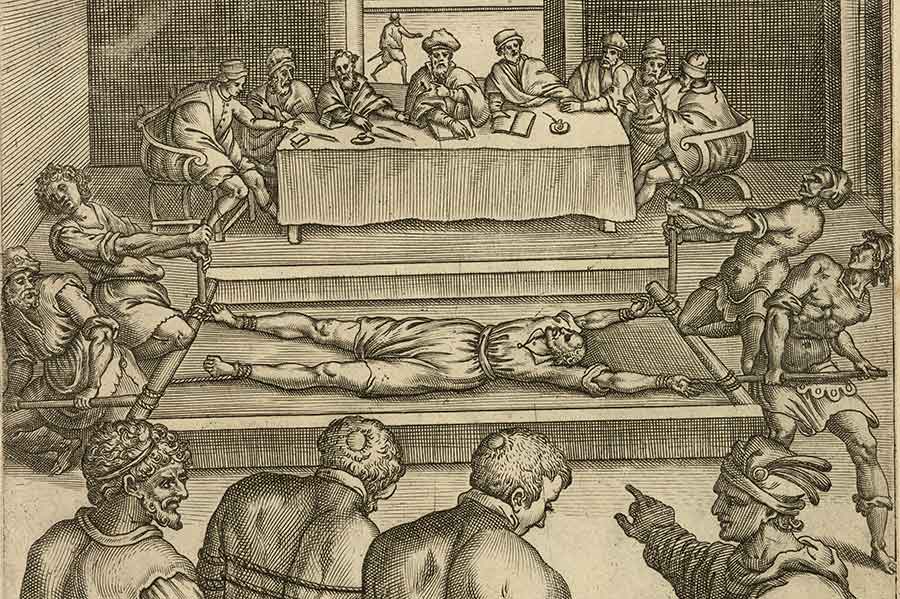

Evening raid, search, and arrest of an Elizabethan Catholic household by Protestant authorities, from Richard Verstegan, Theatrum crudelitum haereticorum nostri temporis (Antwerp, 1587). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

What happens to a religious culture once it is no longer allowed to exist? Where might we look to find the material remnants of a religious community that was gradually suppressed, its holy spaces denuded of their sacred ornaments from time immemorial, its sacred rites banned and public processions outlawed? How can we distinguish its priests once their very existence was made a capital offense under the law, when they were forced to travel under aliases in plainclothes and to hide in secret "priest holes" in private homes to avoid detection during raids by hostile government agents? What does a religious community look like, in short, once it has been hidden away, its sacred rites and rhythms—its calendar of worship and high holy days—all but cancelled from the popular imagination, and any outward forms of expression?

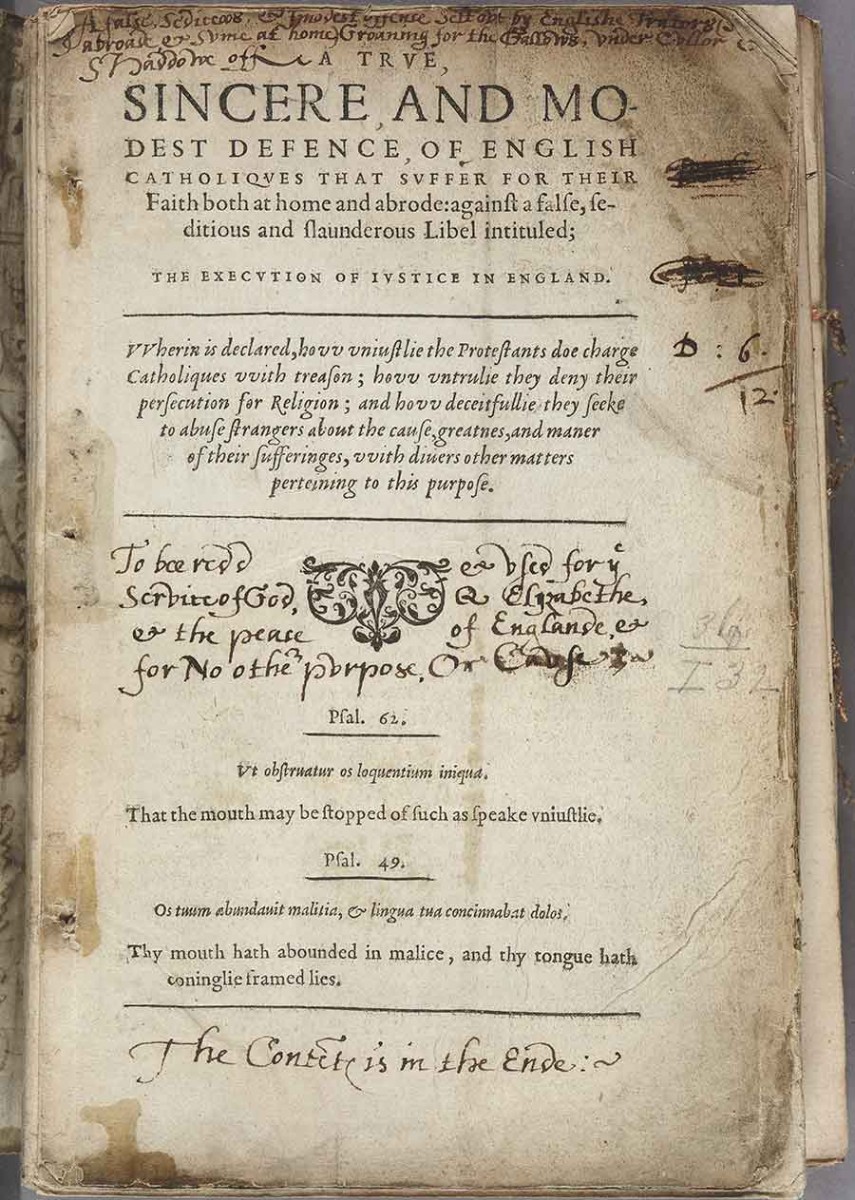

Jesuit priest and martyr, St. Edmund Campion, on the rack, with English scribes at the ready to record his confessions, from Ecclesiae Anglicanae trophaea (Rome, 1584). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

These are questions an international group of scholars will explore November 8 and 9, 2019, in Rothenberg Hall during a conference titled: “Rogue Printers, Book Smugglers, Annotators, & Scribes: The Book Culture of the Elizabethan Catholic Underground.” The Huntington preserves one of the world’s finest gatherings of so-called “recusant” books: books for and about English Catholics who “recused,” or withheld, themselves from official Protestant church services. These rarest of rare books (many preserved today in but a handful of recorded copies) present a richly detailed record of one of England’s most secretive, scattered, and intensely persecuted religious minorities. The Huntington’s encyclopedic collections document this decades-long persecution from its earliest years—when Roman Catholics were first driven underground following the accession in 1558 of the Protestant queen Elizabeth I.

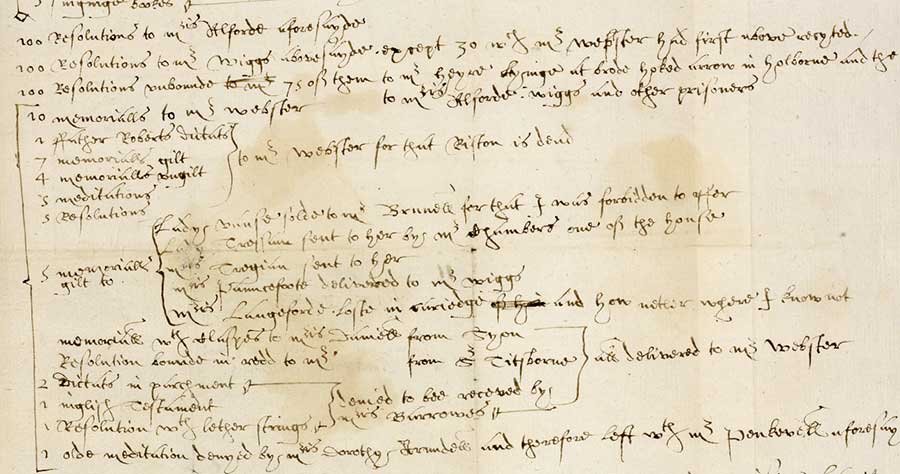

Title page of William Allen’s A true, sincere, and modest defence of English Catholiques (1584). An illicit Catholic book annotated by Richard Topcliffe, the infamous torturer of Elizabethan Catholics “Groaning for the Gallows,” with his further caveat: “To bee redd & vsed for ye Service of God, Q Elizabethe, & the peace of Englande, & for No other pvrpose, Or Cause.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The first sustained efforts of Elizabethan Catholic “missionary printing” can be traced to the early-to-mid 1570s, following a major northern rebellion in support of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, and Pope Pius V’s fateful papal bull Regnans in excelsis (“ruling from on high”), which formally excommunicated Elizabeth and freed her Catholic subjects from their legal obligation to obey her. The crisis years marked by the arrival of the first Jesuit missionaries in England in 1580, the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587, and the failed invasion of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and its bloody repercussions for scores of executed Catholics all remain the stuff of legend and several blockbuster films.

A December 1587 manuscript book smuggling inventory listing 614 illicit Catholic imprints and numerous named women book smugglers and intended recipients. Likely compiled in the Marshalsea Prison, this list was delivered to Joan Aldred, the wife of the Catholic spy Solomon Aldred, employed by Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham. British Library, Lansdowne MS 33/63.

Remarkably, this clandestine literature of the English confessional resistance and “Counter-Reformation” has remained stubbornly hidden in plain sight. A goodly portion of its remnants, concentrated and quietly guarded within the stacks of The Huntington Library, are therefore ripe for fresh scholarly discovery. Indeed, one of the central issues to be explored during the conference is the critical role played over the past four centuries by libraries, archives, and private collections—many of them in remote locations rarely visited—in preserving these precious artifacts as coherent research collections.

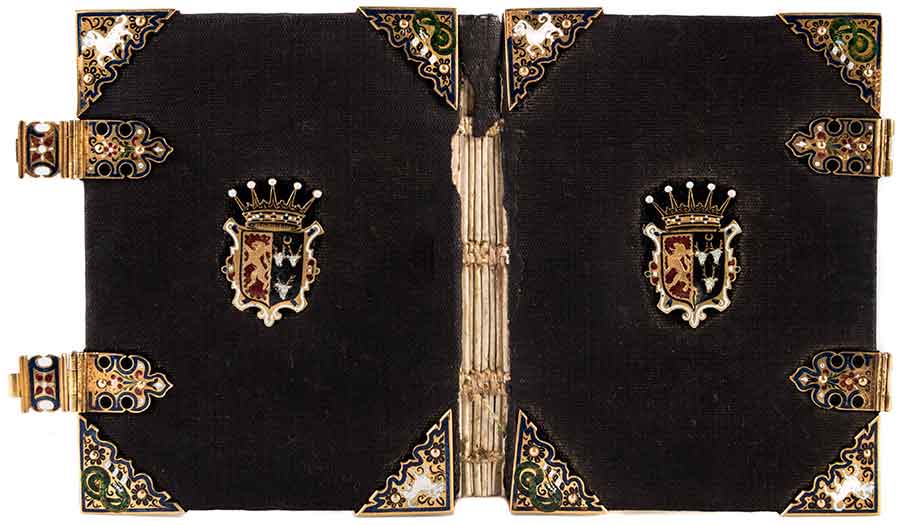

Scribal copy of the Catholic Manual of prayers (n.p., 1583), bound in black velvet and solid gold binding furniture, with champlevé enamel depicting the arms of the Catholic Gilbert and Mary Talbot, 7th Earl and Countess of Shrewsbury. Purchased by the Library Collectors’ Council. This book is on view in the exhibition "What Now: Collecting for the Library in the 21st Century, Part 1" in the West Hall of the Library through Feb. 17, 2020. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Despite a centuries-long emphasis on Protestant triumphalism within the historiography of England, the story of the Elizabethan Catholic underground has enjoyed, in recent decades, renewed interest from historians and literary scholars. Records of confessional ambiguity and coexistence, evidence of clandestine Jesuit missionary activity, the study of lay networks formed by Catholic family marriage alliances and within London prisons, and the wider exploration of England in the context of international Catholicism in Scotland, Ireland, and the European continent—all have broadened our understanding of what it was to be a member of this composite, polyglot, and cosmopolitan religious culture.

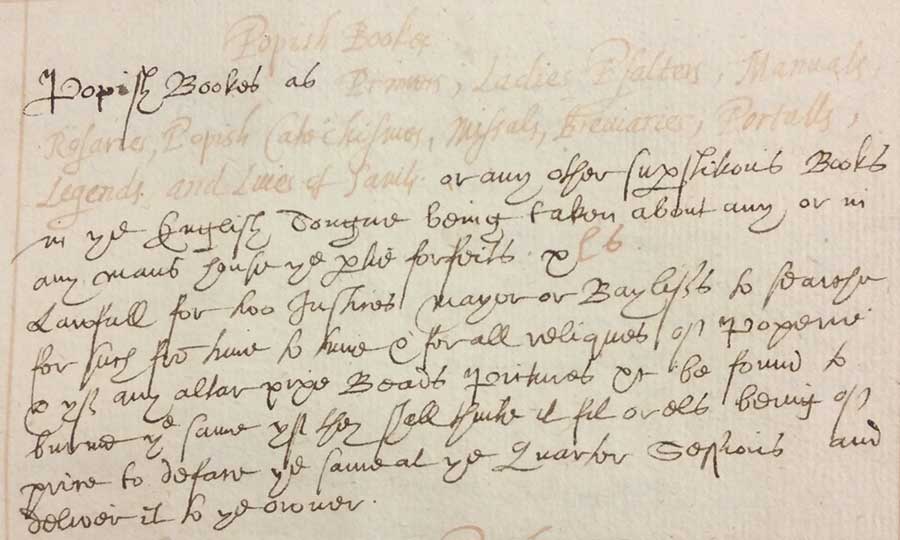

Manuscript description of official English sanctions against “Popish Books,” c. 1605, Egerton Papers. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Less studied, however, is the material evidence of this historical community and its cultural practices, as they were preserved within the pages, bindings, and manuscript marginalia of books. The compilation and copying of these works, their underground printing, and their subsequent circulation and consumption by both lay Catholic readers and antagonistic crown officials—all warrant further exploration. A significant portion of this activity took place in the eminently adaptable (if also more time-consuming, work-intensive, and costly) realm of scribal production, well over a century after Gutenberg’s invention of printing by moveable type.

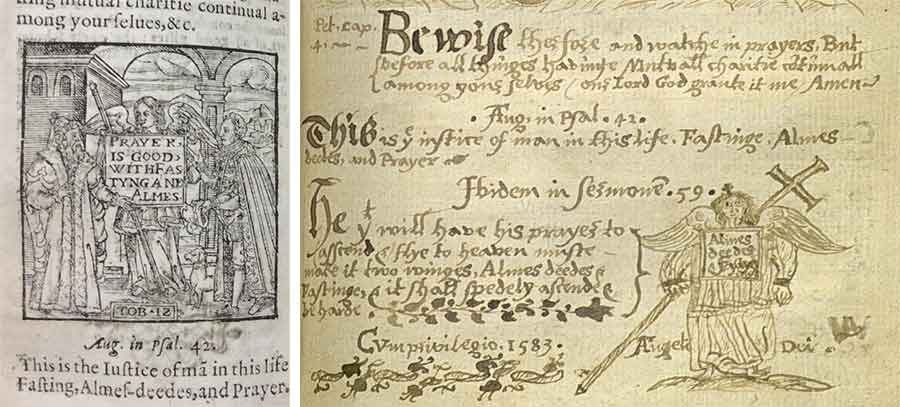

Left: A manual of prayers newly gathered out of many and diuerse famous authors (n.p., 1583), one of three extant copies, Gonville & Caius College Library, Cambridge University. Right: Elizabethan Catholic scribal adaptation of the same text and image. Oscott College Library.

What also remains little studied is the traffic in Catholic books between post-Reformation England and the continent, particularly of seemingly noncontroversial devotional works that nonetheless captured what it meant to be an Elizabethan Catholic at the time—books of spiritual consolation, catechisms, liturgical writings, martyrologies, spiritual meditations, and much more. Roughly one-third of these spiritual works were translations of continental Catholic authors, introducing the theology of the Counter-Reformation into England for the first time on a large scale. So, too, has the particularly rich tradition of Catholic scribal publication been left relatively unattended in this period of constricted access to print, particularly within England.

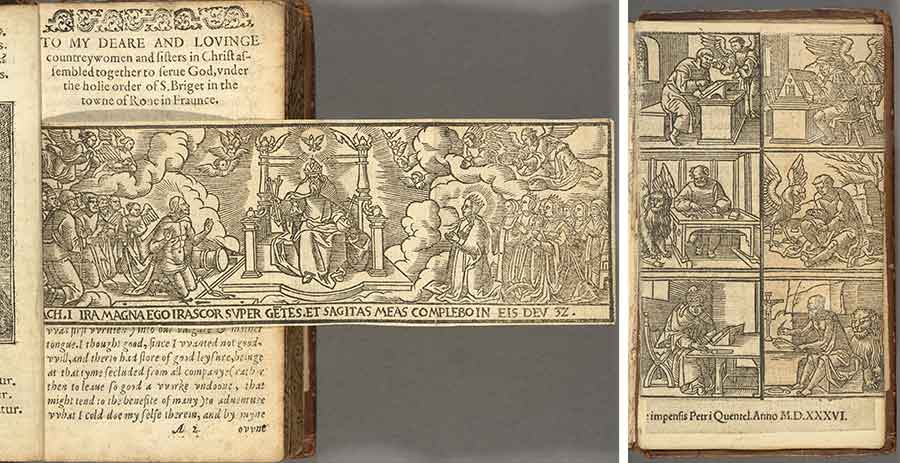

Left and right: Diego de Estella, The contempte of the world, and the vanitie thereof (Rouen, 1584), one of 13 known copies, this one uniquely extra-illustrated with woodcut engravings cut from an imprint issued from the Cologne press of Peter Quentell decades earlier in 1536. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Scholars will come to The Huntington to examine the funding and commerce of Elizabethan Catholic print and scribal production; probe the intellectual and economic relationships that guided the careers of Elizabethan Catholic printers; interrogate patterns of book circulation and readership; assess the demonstrable influence and immediate cultural impact of particular Catholic books among both lay and priestly readers; investigate the early collecting of illicit Catholic libraries; explore scribal networks linked through relationships of patronage and clientage; and more.

Three pages of The Rosarie of our Ladie. Otherwise called our Ladies Psalter (Antwerp, 1600). The first two engravings hand-colored subtly with green leaves and white roses, the third with additional brilliant red to reflect the “glorious” mysteries of the Resurrection of Christ. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Earle Havens is Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, and director of the Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance, at Johns Hopkins University.

Mark Rankin i s 2019–20 Roop Distinguished Professor of English at James Madison University and editor of the journal Reformation .