The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Newton You Didn’t Know

Posted on Tue., Jan. 7, 2020 by

Illustration of Isaac Newton (1643–1727) in Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or Universal dictionary of arts, sciences & literature . . . compiled, digested, and arranged by John Wilkes . . . assisted by eminent scholars, London, Adlard, 1810–29. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Isaac Newton (1643–1727) is generally regarded as one of the most significant individuals in the history of science, and he is remembered principally for his work on natural philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy. In addition to articulating the laws of motion that laid the foundation for classical mechanics, Newton was the first person to formulate a law of universal gravitation and also co-invented calculus (at the same time as his nemesis Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz). Indeed, Newton has thus often been portrayed as the incarnation of scientific genius who overturned superstition and ushered in the Age of Reason.

So, when it came to light in the early 20th century that Newton was not only a practicing alchemist but also entertained heterodox interpretations of Christian theology and spent a great deal of time, for instance, attempting to unravel numerological Biblical codes, the understanding of Newton as the icon of modern science was thrown into question. In his 1946 essay "Newton, the Man," the British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) succinctly captured this sentiment when he wrote that “Newton was not the first of the age of reason: He was the last of the magicians.”

In recent years, however, historians of science have explored the diverse aspects of Newton’s thought to give a more nuanced portrait, and beyond compelling us to reconsider our understanding of Newton the man, this work has been central to a broader rethinking of some of our assumptions about the history of science. Scholars are still untangling the complexities of Newton’s thought, but their work has generally pointed toward a more coherent understanding of Newton where, for example, his alchemical pursuits informed other parts of his natural philosophy.

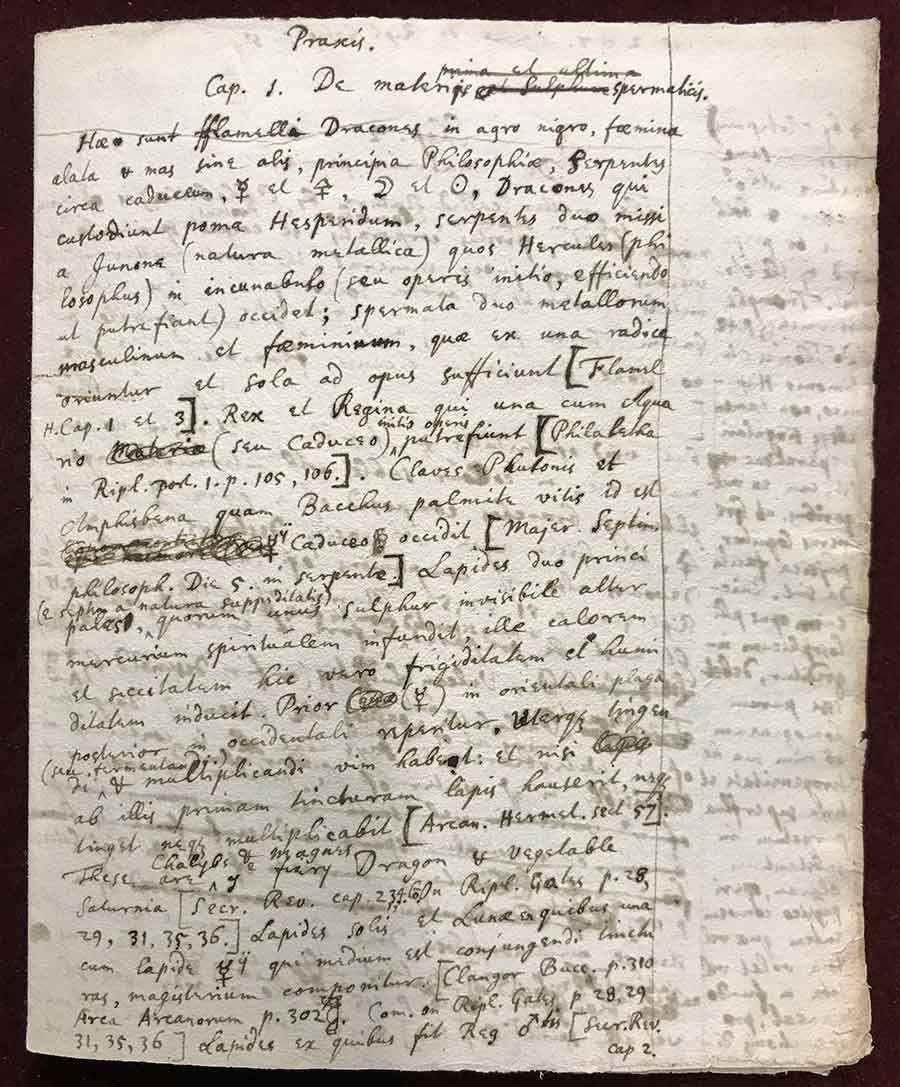

The alchemical treatise “Praxis,” dated to the 1690s, contains Newton’s attempt to decipher the process of synthesizing the philosophers’ stone from a variety of other alchemical texts. The Grace K. Babson Collection of the Works of Sir Isaac Newton at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington has played an important role in this rethinking of Newton as it is home to the largest collection of Newtoniana in the United States. A majority of our Newton holdings are on loan from Babson College (in Wellesley, Massachusetts), whose founder, Roger Babson, and his spouse, Grace K. Babson, were major collectors. The Babsons’ interest in Newton sprang from the idea that human relations and economic markets were governed by Newton’s law of action and reaction—just as objects in the physical world are. In addition, Roger Babson was an entrepreneur and business theorist whose philosophy, much like Newton’s, both bucked convention and was fiercely ambitious.

Recognizing the importance of the Newton materials to cultural heritage and scholarship, the Babsons committed to preserving the collection and making it available for use, and so in 1995, it was placed on deposit at the Burndy Library of the Dibner Institute at MIT. Then, in 2006, the entire Burndy Library, including the Babson Collection, came to The Huntington, where our preservation and curatorial staff care for the materials, and where scholars from around the world continue to explore Newton’s diverse interests.

Babson’s Newton materials have been featured in the permanent Library exhibition “Beautiful Science” as well as in the current exhibition in the Library’s West Hall, “What Now: Collecting for the Library in the 21st Century, Part 1” (on view through Feb. 17). In addition, The Huntington hosted a conference in 2014 devoted to Newton, titled “All in Pieces? New Insights into the Structure of Newton’s Thought,” which was supported by funds from the Dibner History of Science Program at The Huntington.

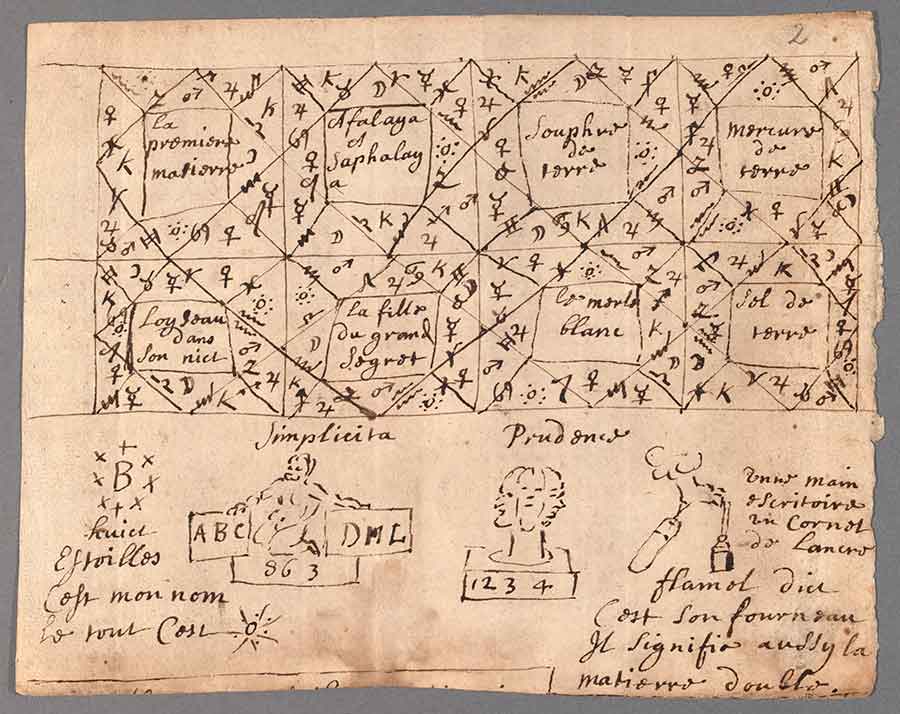

This small manuscript has numerous alchemical and astrological drawings in Newton’s own hand. Newton was a voracious reader of alchemical literature, and it is clear that he drew much of the material in this manuscript from other alchemical texts, including, for instance, one that discussed a pseudonymous alchemical author claiming to be Nicolas Flamel (ca. 1330–1418). The Grace K. Babson Collection of the Works of Sir Isaac Newton at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

William R. Newman, professor at Indiana University and the 2014–15 Eleanor Searle Visiting Professor in the History of Science at Caltech and The Huntington, recently published Newton the Alchemist: Science, Enigma, and the Quest for Nature’s “Secret Fire,” a book which drew extensively from the alchemical manuscripts in the Babson Collection. Especially important was the so-called “Praxis” manuscript, which Newman describes as “The most highly developed extant specimen of Newton’s attempt to work out the processes of the adepts.”

Since the Enlightenment, alchemy has often been considered a pseudoscience that hindered scientific progress, but Newton’s alchemical manuscripts show that, just like his work in physics and mathematics, his work in alchemy combined theory and practice, careful reading with hands-on experimentation—and demonstrated his extraordinary attention to detail. Like his physics, it showed what Newton thought to be his best quality: what he called “patient thought.” We also see that Newton was motivated by a profound curiosity and the belief that no intellectual challenge was too daunting to tackle—even unlocking the secrets of the material world. Beyond this, though, Newman is among a group of historians who have shown that the alchemy practiced by Newton and other aspirants to the philosophers’ stone had an important influence on the emergence of modern science, for instance on the development of the theory of atomism and the concept of mass balance, the notion that the input mass of a chemical process must equal the output.

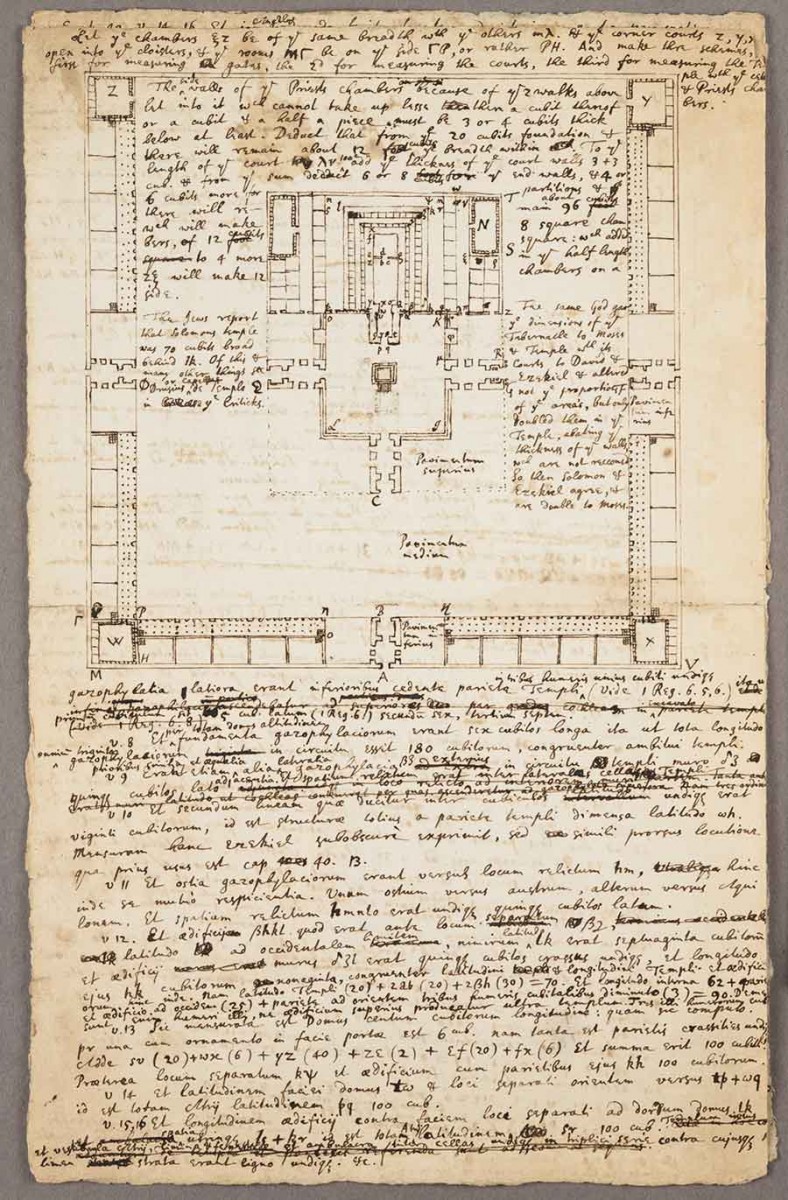

Isaac Newton, A treatise or remarks on Solomon’s Temple. “Prolegomena ad lexici prophetic partem secundam in quibus agitur De forma sancturaii Judaici . . . Commentarium” (after 1690). Newton believed that the architecture of Solomon’s Temple held divine secrets that had long ago been lost. He based his description and this sketch upon detailed comparisons of the biblical Hebrew text with the Septuagint and the Vulgate versions. The Grace K. Babson Collection of the Works of Sir Isaac Newton at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Babson Collection has also been central to the reevaluation of Newton’s religion. Over the course of his extraordinarily productive life, Newton wrote more on religious topics than he did on all of his scientific interests combined. His contemporaries considered him an erudite and astute theologian, but had all of his views been made public, he would undoubtedly have received a more negative appraisal. In short, by the standards of his era, Newton was a heretic. Most egregiously, he denied the trinity and believed that Christ was a creation of God.

Newton was also heavily invested in biblical prophecy, chronology, and even the symbolic interpretation of biblical architecture. The “Solomon’s Temple” manuscript is arguably the most outstanding item in the Babson Collection and was written at a time when the determination of the dimensions of Solomon’s Temple was a major puzzle in theological inquiry. Newton believed that the architecture of the temple held coded ancient secrets about God and the universe, and he was far from alone in this. Science and religion have often been portrayed as bitter antagonists, but the study of individuals like Newton has revealed a much more complicated picture.

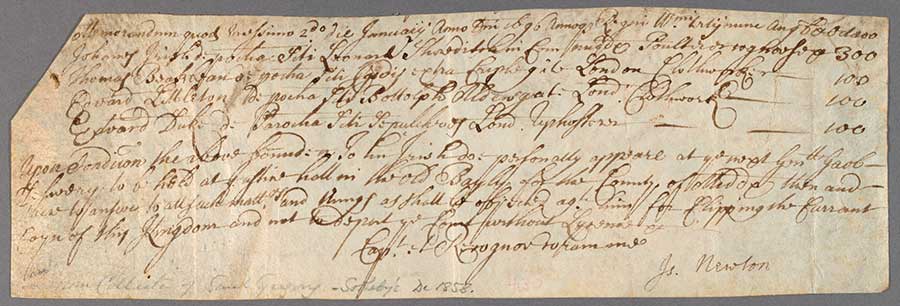

This official document, countersigned by Newton, is from his early years as warden of the Royal Mint. It is a certificate of bail in the amount of ₤300—not an insignificant sum—for one John Irish, who was accused of clipping coins. The Grace K. Babson Collection of the Works of Sir Isaac Newton at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Another area of the Babson Collection that scholars have recently explored concerns Newton’s time at the Royal Mint. By the final decade of the 17th century, Newton had garnered significant celebrity for his work in physics and mathematics, and as a result, he was offered the position of warden (1696–1700) and then master (1700–1727) of the Royal Mint. Newton took very seriously what was supposed to have been a formal sinecure at the mint and involved himself in the reform of currency and even the prosecution and punishment of coin clippers and counterfeiters. The Babson Collection has several manuscript documents that were issued by the mint and show that Newton carried out his administrative affairs with the same assiduousness as his physics and mathematics, including the prosecution of these crimes (which were punishable by death).

Newton’s genius is strongly resistant to simple characterization, and while it is now clear that he was neither an Enlightenment rationalist nor an irrational magician, there continue to be many questions about how the diverse areas of his thought worked together. Whatever the answers to these questions reveal, the Babson Collection will undoubtedly continue to help scholars uncover new aspects of Newton and the history of science that we didn’t know.

On Wednesday, Jan. 8, at 7:30 p.m. in Rothenberg Hall, Rob Iliffe, professor of the history of science at the University of Oxford, will deliver his Dibner Lecture, titled “The Uses of Evidence in the Newton-Leibniz Priority Dispute.” The 17th-century dispute between mathematicians Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over who first invented calculus was a major intellectual controversy for decades. Iliffe will discuss two little-known documents that reveal how Newton’s approach to prosecuting contemporary counterfeiters as a warden of the Royal Mint was closely aligned to his strategy for revealing corruption in Christianity. Free; reservations required.

Joel A. Klein is the Molina Curator of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington.