Posted on Tue., March 3, 2020 by

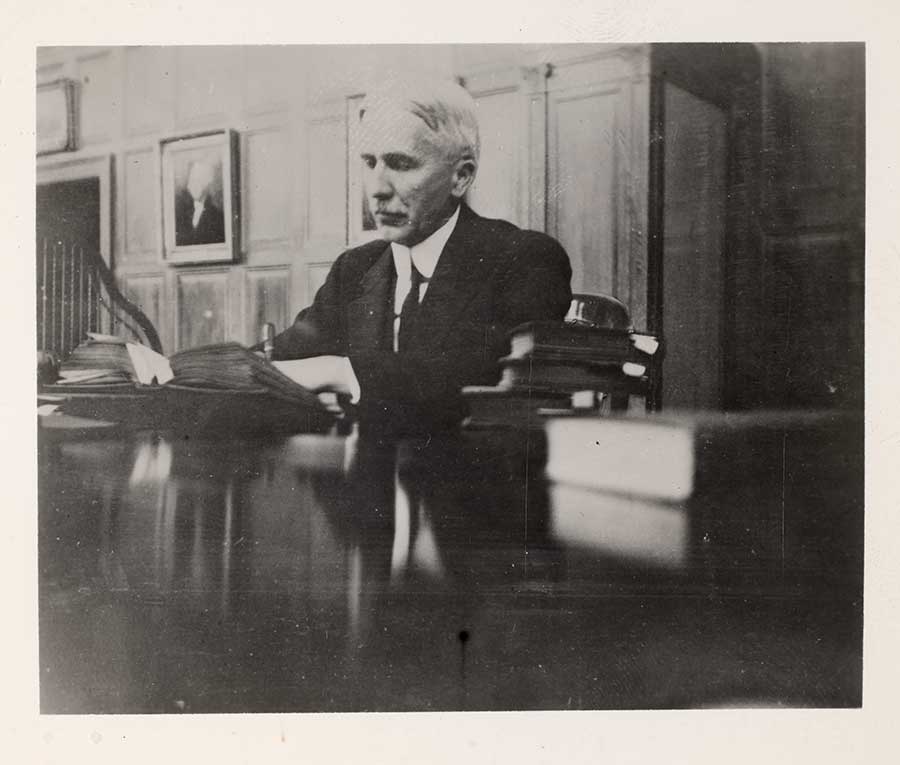

One might assume that the first researchers at The Huntington had all been men (like Archibald Bouton of New York University, pictured here in the main reading room in 1924). But among the very first readers was Mary Floyd Williams, a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley, who first used the Library's resources in 1920.

The Huntington's readers are at the heart of the Library's mission, and a historically important letter in The Huntington's institutional archives offers evidence on who the first readers were, a fact especially worth examining while The Huntington celebrates its Centennial.

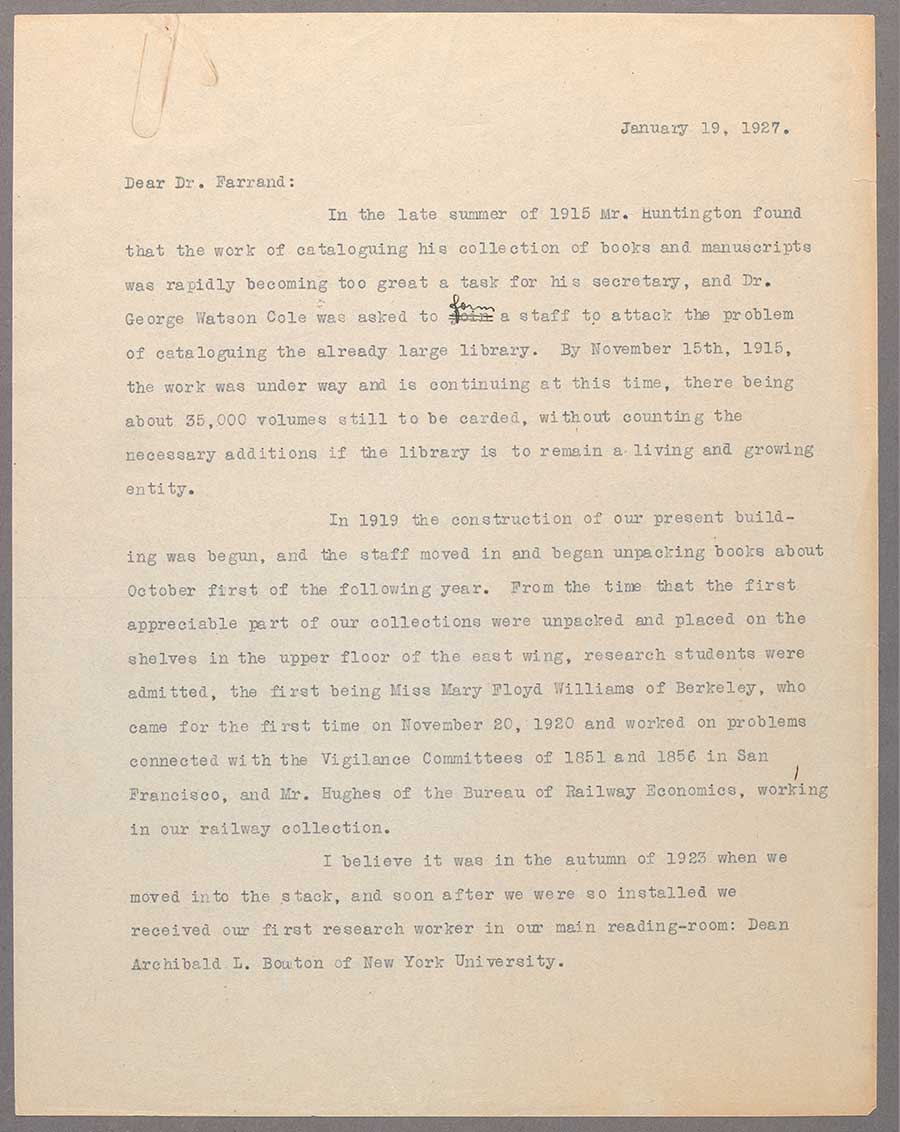

In a typed letter dated January 19, 1927, librarian Leslie Edgar Bliss responded to an inquiry about the history of Henry E. Huntington’s library from Max Farrand, a distinguished historian of colonial America about to be named the first director of The Huntington. Farrand was obviously doing his homework before his appointment, and Bliss was the person to ask: He had worked for Huntington since 1915 and had become the The Huntington’s chief librarian. In recounting the Library’s history for Farrand, Bliss discusses The Huntington’s first readers and in so doing also touches on other revealing aspects of the Library’s early history, such as the use of library collections and where readers worked in the library.

A letter dated January 19, 1927, from librarian Leslie Edgar Bliss to Max Farrand, a distinguished historian of colonial America, who was about to be named the first director of The Huntington. In the second paragraph, Bliss identifies the first two readers at The Huntington as “Miss Mary Floyd Williams of Berkeley” and a “Mr. Hughes of the Bureau of Railway Economics.”

Who were the first readers? In the second paragraph of his methodical letter, Bliss pinpoints the first two readers as “Miss Mary Floyd Williams of Berkeley” and a “Mr. Hughes of the Bureau of Railway Economics.” They came, Bliss writes, because the unpacking of Huntington’s library after the move from New York to San Marino in 1919 led to the opening of the Library to researchers in the fall of 1920. Williams first used The Huntington’s resources on November 20, 1920, and Hughes did so at roughly the same time. Williams is easy to identify; Hughes, less so.

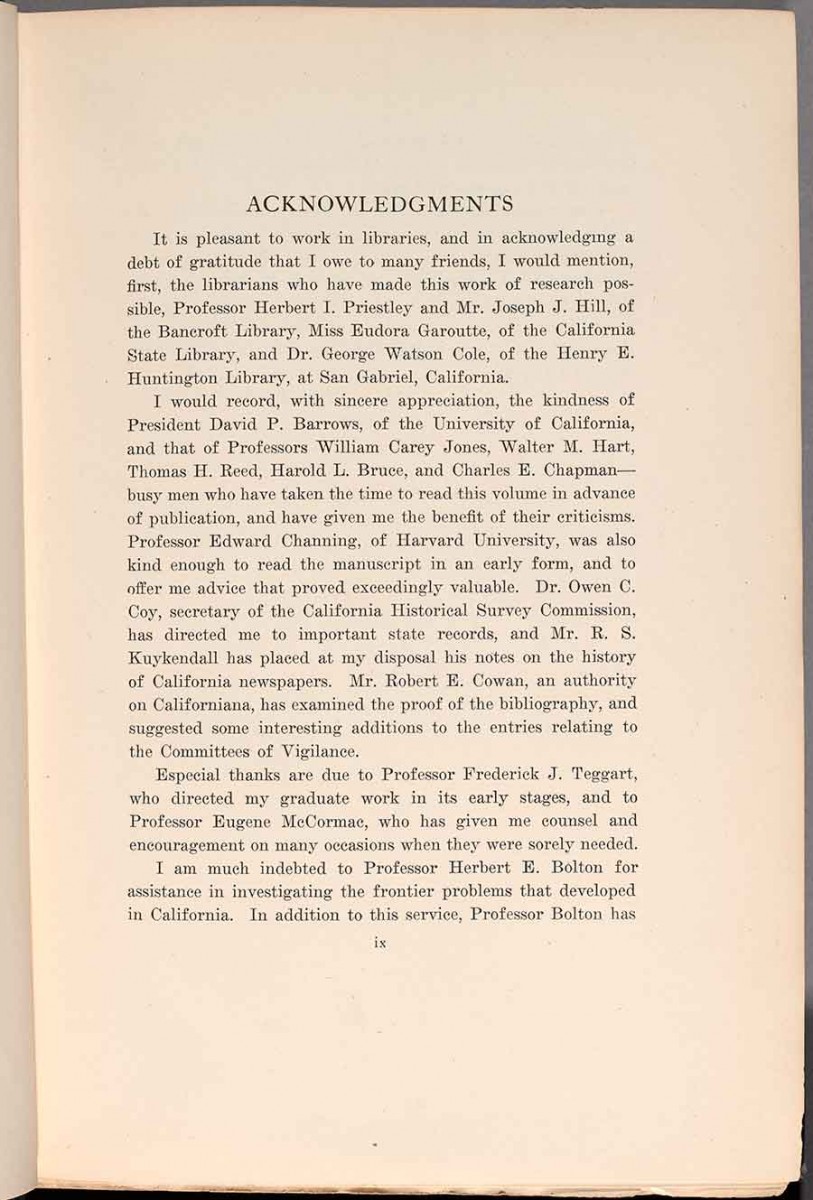

Mary Floyd Williams was a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley, and her dissertation concerned the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851. She came to The Huntington, Bliss notes, to examine the records of the committee of 1856, obviously as a point of comparison to the work of vigilantes in San Francisco in 1851. Williams’ acknowledgements in the forward of her book based on her dissertation support Bliss’s statement. She thanks George Watson Cole for his help at The Huntington; Cole was The Huntington’s chief librarian in 1920, when she conducted her research.

The acknowledgements page in the forward of Mary Floyd Williams’ book, based on her doctoral dissertation, about the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851. One of the first two readers at The Huntington, Williams was a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley. At the end of the first paragraph of Williams’ acknowledgements, she thanks George Watson Cole for his help; Cole was The Huntington’s chief librarian in 1920, when she conducted her research.

The collection she consulted, the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance records, was part of Huntington’s first major acquisition of materials in California history, which came in 1916 with his purchase of the holdings of a major collector of Californiana, Augustin S. MacDonald. This purchase laid the foundation for The Huntington’s extensive holdings in California history that today make it one of the premier repositories for the study of the state’s past. During her post-Huntington time, Williams proved that there is life after graduate school. She traveled extensively in Asia, leaving a collection of her lantern slides taken there to UC Berkeley; taught in the UC Berkeley extension program; and even published a novel.

Perhaps reflecting the passage of seven years since he met the first readers, Bliss’s description of “Mr. Hughes of the Bureau of Railway Economics” is less informative than that for Williams. Located in Washington, D.C., the Bureau of Railway Economics was the premier library for the study of American railroads. There was a Lotus G. Hughes who worked there in 1915, according to the American Library Association Handbook of that year—but there is no way to guarantee that this was the same Hughes. Bliss only lightly describes Mr. Hughes’s object of research, calling it “our railway collection.” This may have been what was then called the “Railroad Collection” and is now called the “International Railroad Collection.” Purchased from Anderson Galleries in 1919, the collection documents the history of railroads in Great Britain and Australia.

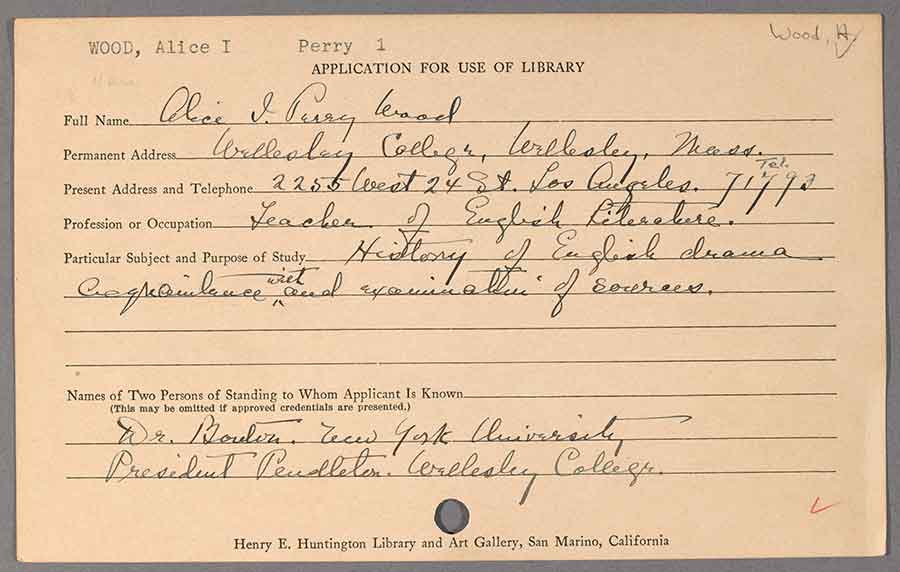

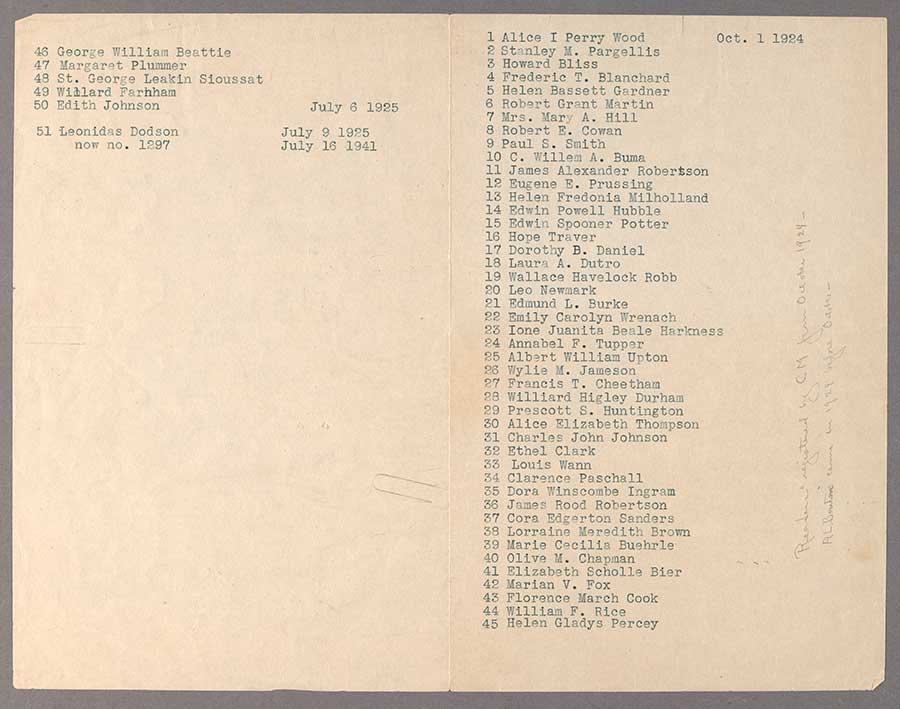

The first reader at The Huntington given a registration card was Alice I. Perry Wood of Wellesley College, a scholar of English drama. The year was 1924. Curiously, Archibald Bouton served as one of her references.

After discussing Williams and Hughes, Bliss informed Farrand that Archibald L. Bouton, dean of New York University’s College of Arts and Pure Science, was the first reader to use The Huntington’s main reading room when it opened in 1924. The main reading room was located in what is now the main exhibition hall; perhaps readers previously had worked in what is now the Trustees Room. After all, Bliss, in his letter, ties the unpacking and shelving of the first collections in the upper stacks of the east wing of the Library with the admission of Hughes and Williams as first readers. Unlike his discussion of this pair of readers, Bliss neglects to mention the collections that Bouton consulted. As a member of the English department at NYU, Bouton had edited the Lincoln-Douglas debates. By 1924, The Huntington had purchased collections from such early stalwarts of Lincoln collecting as William Harrison Lambert and Judd Stewart, and those materials would have been available for Dean Bouton to consult.

In 1936, Bouton returned to The Huntington to carry out more research, as his reader application of that year shows. In the section of the application concerning libraries consulted, an unnamed staff member wrote: “Dean Bouton came to the library to read in 1924—the first reader to use material here—no registration card.” The admission of readers had obviously become routine—the first reading room reader probably did not even formally register. Nor does a registration card now exist for either Mr. Hughes or Mary Floyd Williams. In fact, as Avery Deputy Director of the Library Laura Stalker has discovered, the first reader given a registration card, also in 1924, was Alice I. Perry Wood, of Wellesley College, a scholar of English drama. Curiously, Bouton served as one of her references.

List of readers with note in pencil on Archibald Bouton’s preceding Alice I. Perry Wood.

Regarding Bouton’s reference for his 1936 application, someone succinctly wrote: “Introduced by LEB,” obviously Leslie Edgar Bliss, who most likely had provided the staff member filling out the form with the information about Bouton’s being the first reader. Bouton would eventually settle in Pasadena, where he died in 1941.

As a final note: Bouton had a companion as he traveled from New York City to San Marino to work at The Huntington in 1936: his daughter, Mary, who also applied to become a reader. The application for the Master’s student in English at Wellesley was also approved. This father and daughter pair are only two of the thousands of readers the Library has served during its 100 years in San Marino.

Clay Stalls is the curator of California and Hispanic Collections at The Huntington.