The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Chinese in the Huntington Archives

Posted on Wed., April 8, 2020 by

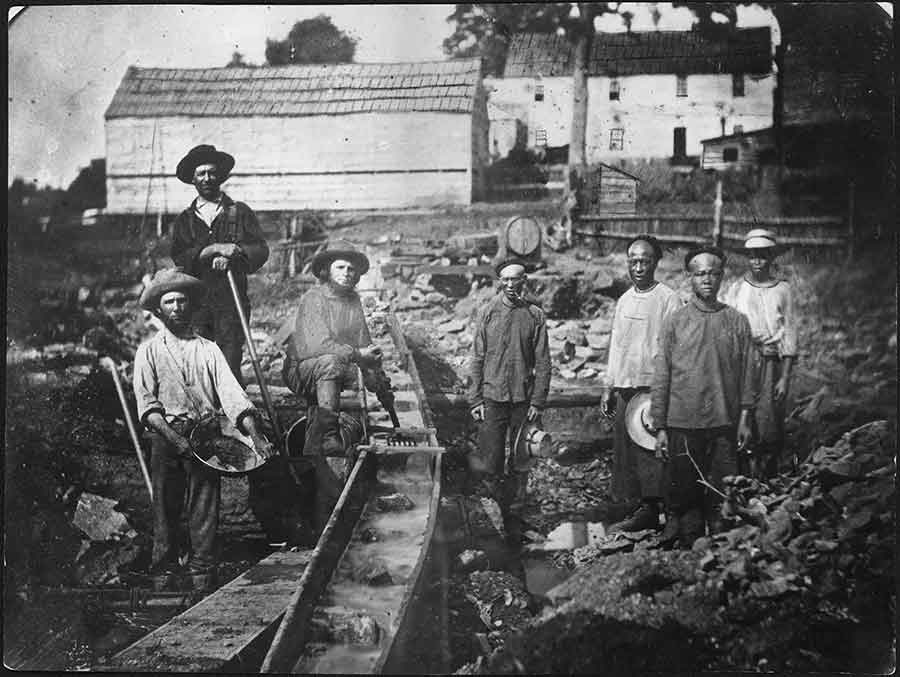

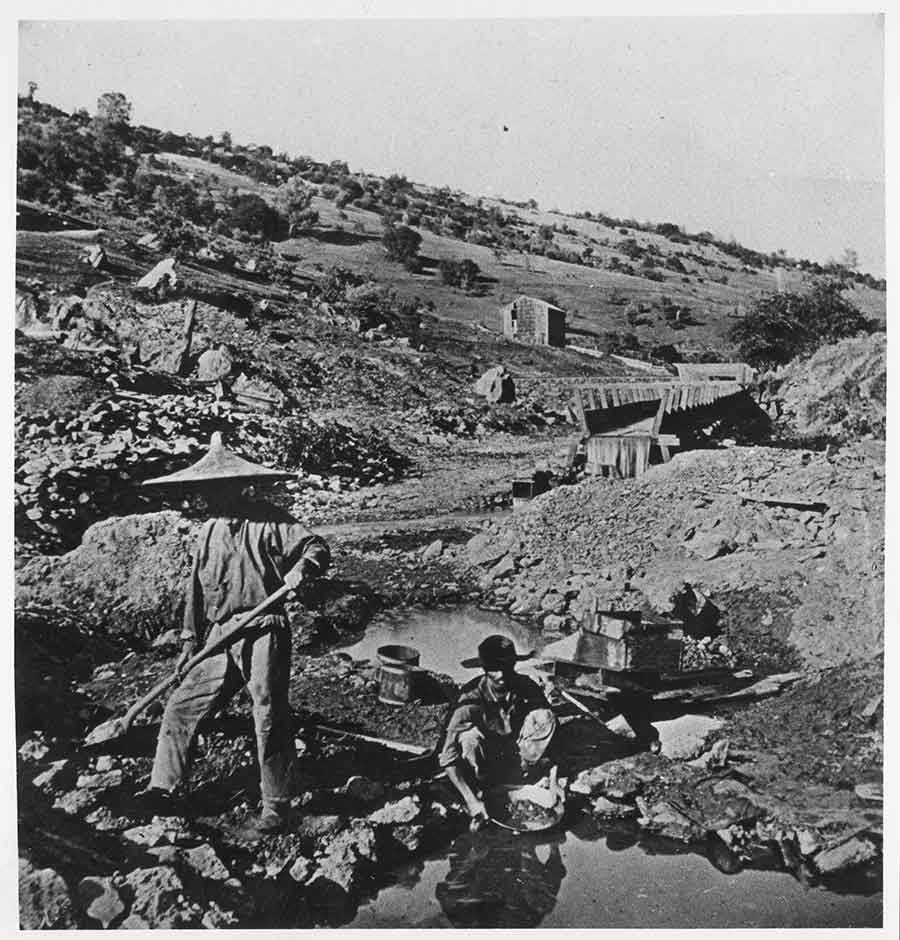

Miners at Auburn Ravine, California, 1852. Unknown photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

To refute the long-held assertion that the Chinese who labored in California's Gold Rush were all indentured servants, Mae Ngai delved deep into The Huntington's collections of Western American History. In her lecture this year at The Huntington, "The Chinese in the Huntington Archives: Hiding in Plain Sight," Ngai made her case, revealing the daily lives of the Chinese in California's gold mining counties through original sources from the 19th century.

Ngai, a professor of history at Columbia University, has nearly completed her book on the formation of Chinese diaspora communities that arose from the gold rushes of the 1800s. She describes sources on Chinese in the California Gold Rush as “scant and scattered” and her research as “finding needles in hundreds of haystacks.” The Huntington facilitated her effort through a research guide compiled by Library curators Peter Blodgett and Li Wei Yang. Ngai went through scores of letters, diaries, journals, newspapers, guidebooks, travel narratives, and photo albums to illuminate many dimensions of the Chinese experience.

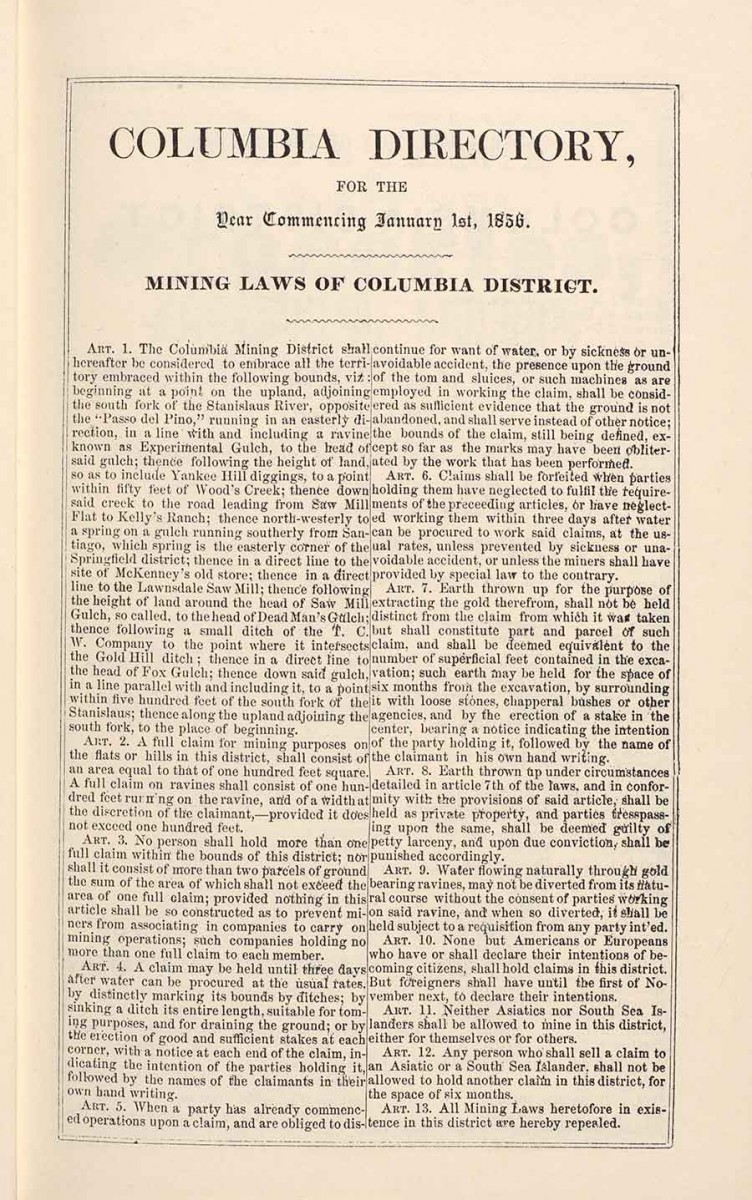

“Columbia Directory with Mining Laws of Columbia District,” from the Miners and Business Men’s Directory, originally published in Columbia, California, by Heckendorn & Wilson, 1856. The Columbia District was the only district out of 30 in Tuolumne County that cited the exclusion of Chinese. For example, Article 11 states: “Neither Asiatics nor South Sea Islanders shall be allowed to mine in the district, either for themselves or for others.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

An 1852 photo taken at Auburn Ravine, located a little more than 30 miles northeast of Sacramento, shows both white and Chinese workers, prompting questions from Ngai that demonstrate how historians use archival materials to think about history. The image was clearly composed by the photographer. The whites are obviously miners, but what is the role of the Chinese? What is the relationship between the two groups? Were the Chinese part of a work gang, or did they work individually?

According to exclusionary laws at the time, Chinese could work only abandoned claims or claims sold to them by whites. But how extensively were these exclusions applied?

Ngai found clarity in such sources as the Miners and Business Men’s Directory of 1856 for Tuolumne County. Such directories are extremely rare, but they contain a wealth of detail, such as who owned which mining claims. Only one district (the Columbia District) out of 30 in Tuolumne County cited the exclusion of Chinese. Directories noted claims owned by Chinese, indicating that the Chinese knew the rules regarding registering claims and obeyed them. Racism existed, but exclusions were applied unevenly.

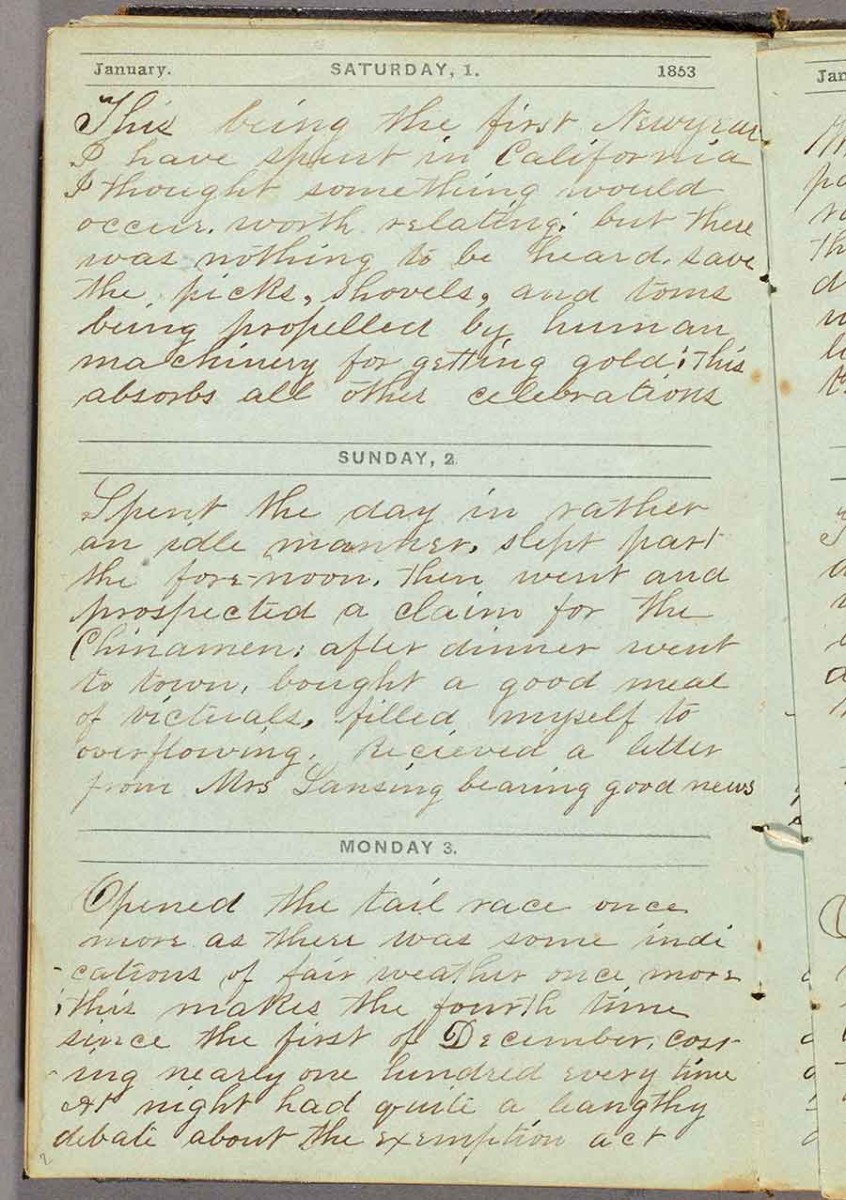

The diary of the gold miner H. B. Lansing, 1853. On Jan. 2, Lansing wrote: “Spent the day in rather an idle manner, slept past the forenoon, then went and prospected a claim for the Chinamen.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

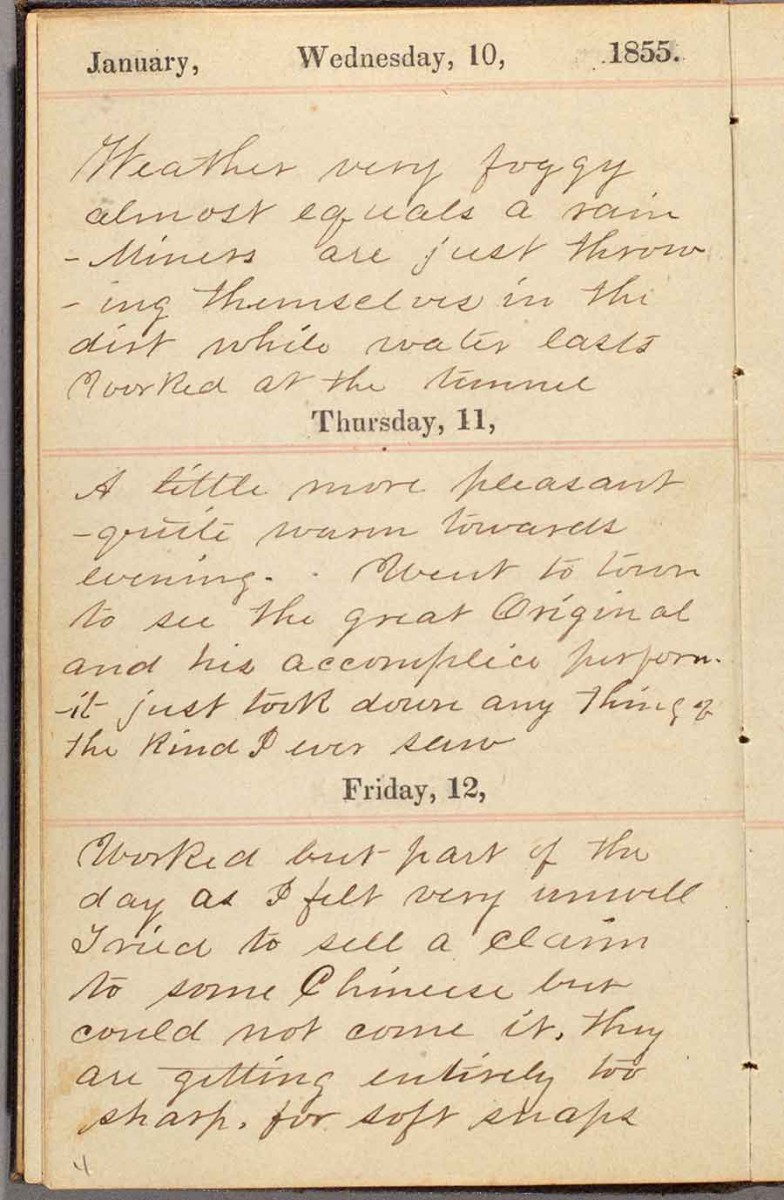

The diary of H. B. Lansing from Tuolumne and Calaveras counties in 1853 and 1855 shows the interaction between Chinese and whites. Lansing hired Chinese workers as well as Europeans, and he states in one entry that he “prospected a claim for the Chinamen.” Lansing indicates his ethnic bias in summarizing an unsuccessful attempt to sell a failed claim to the Chinese—“they are getting entirely too sharp”—yet, in an earlier entry, he recounts taking “dinner at the Chinamans.” The Chinese were clearly an integral part of his world.

The ledgers of the El Dorado Water and Deep Gravel Mining Company and account books of general store owner Andrew Brown of Kernville yield a picture of the lives of work gangs. The gangs built the infrastructure of the gold country, digging miles and miles of sluices and blasting hillsides.

The diary of the gold miner H. B. Lansing, 1853. On Jan. 12, Lansing wrote: “Worked but part of the day as I felt very unwell. Tried to sell a claim to some Chinese but could not come it. They are getting entirely too sharp . . .” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Both the El Dorado company and Brown kept records of the Chinese separate from those of whites. Ngai found El Dorado employed 800 Chinamen per day during one four-month stretch.

Andrew Brown records that a man named “China Joe” bought rice, candles, whiskey, tobacco, tea, sugar, ham, and oysters at his general store and paid in cash. Another Chinese man paid in vegetables, cash, and gold dust for his rice, barley, and stagecoach fare. A third purchased tools, duck, and oysters; payment was deducted from his wages.

For Ngai, these logs indicate that the Chinese were a part of the society in which they lived and worked, “and yet apart.” Whites separated out the Chinese in their practices and in their minds.

Chinese workers “panning out.” Unknown date and photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The town of Chinese Camp in Tuolumne County speaks to the social structure of Chinese during the Gold Rush. The town had 1,000 people, 200 of whom were white. Chinese-owned restaurants and laundries were community hubs. The town had three temples, large buildings with rich decorations and plantings of persimmon trees, narcissus, and trees of heaven (a pungent variety of sumac). Yet the Chinese in Chinese Camp were nowhere to be found in the county’s directories.

Ngai hopes her book will contribute to reclaiming and interpreting the Chinese in 19th-century California as the real people they were—neither relegated to separate ledgers nor invisible in the official records of the time.

You can listen to Mae Ngai’s lecture, "The Chinese in the Huntington Archives: Hiding in Plain Sight,” on SoundCloud.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.