The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Year Was 1970

Posted on Wed., May 13, 2020 by

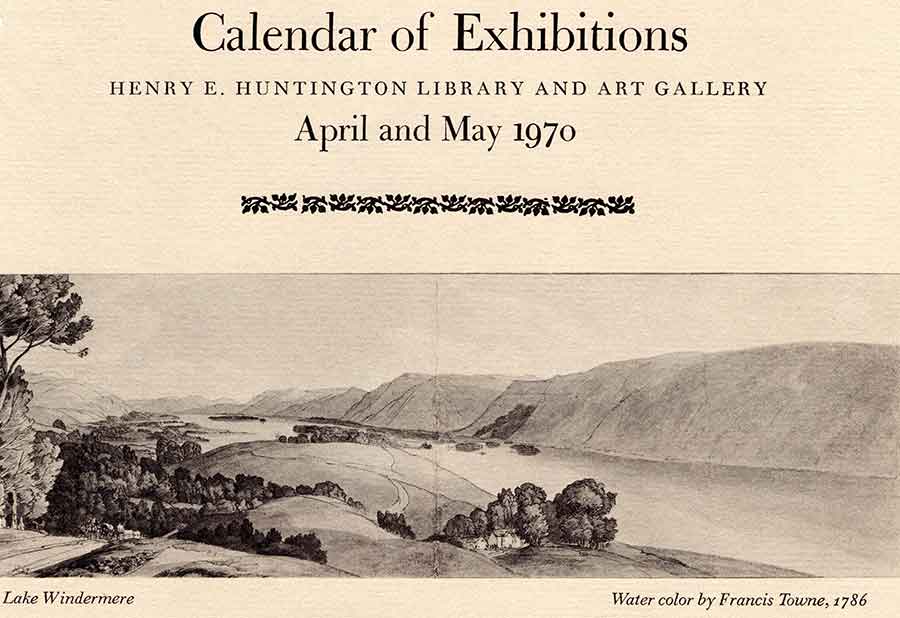

The year 1970 was a tumultuous one for the nation—as 2020 is today—but The Huntington was an oasis of calm, offering intellectual engagement and spiritual renewal through nature, the humanities, and the arts. Today we look back at 1970 as represented in the pages of The Huntington's bimonthly newsletter from that year. The April/May issue highlighted a bicentennial exhibition on the poet William Wordsworth. Pictured on the front page was a serene view of Lake Windermere in England's Lake District, where Wordsworth was born. Watercolor sketch by Francis Towne, 1786. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington’s bimonthly newsletter has been in print for more than a half-century. Originally a slim, single-fold brochure known as the Calendar of Exhibitions, the early version served the same purpose that the expanded, full-color Calendar has served more recently: keeping Members and the public informed about exhibitions and public programs, new acquisitions, botanical research, noteworthy plants, educational outreach, and the robust intellectual life of the institution. While the printed Calendar is on hiatus (along with all programming) during the COVID-19 closure, we thought it would be enlightening to travel back in time for a peek at what was going on at The Huntington 50 years ago.

The year 1970 was a tumultuous one across the U.S. The Vietnam War was raging, President Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia, and thousands of students faced off against the National Guard at protests and peace marches on college campuses. It was also the year that Earth Day was established amid global concern for the environment. The Huntington was a haven from the turmoil as well as a place for taking solace in nature and seeking knowledge and insight. It also invited visitors to draw inspiration from human achievement as represented in the collections.

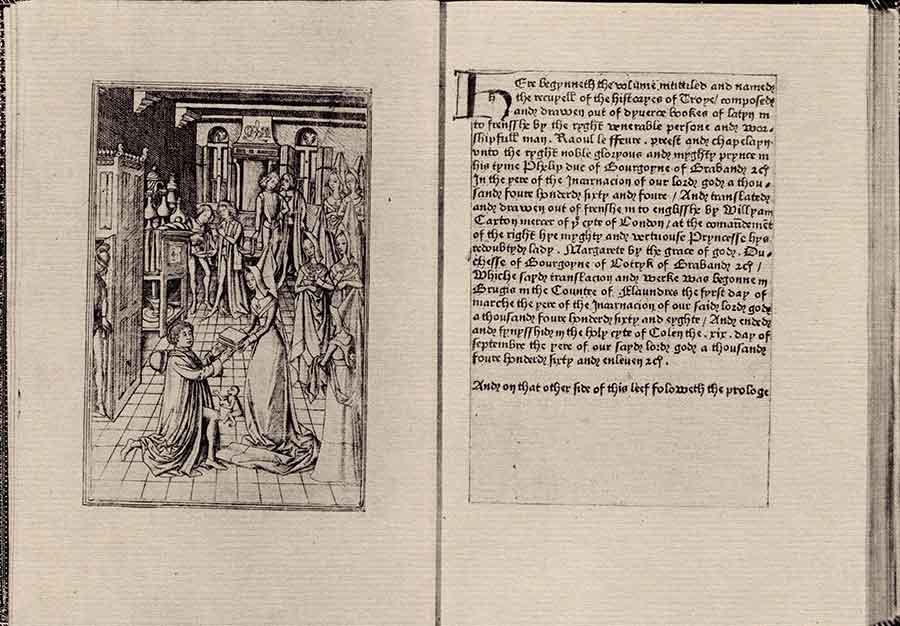

The first printed book in the “englysshe tonge” was Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (“A Collection of the Histories of Troy”), published by William Caxton around 1475. The Huntington’s unique edition was one of the highlights of an exhibition on early English printing that was promoted in the newsletter in 1970. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

With the Library’s vast holdings of rare books and manuscripts, exhibitions drawn from the vaults are ideally suited to spotlighting human achievement through the centuries. One such offering in 1970 was “Early English Printing, 1475–1525.” The printing press—and the resulting rise in literacy—didn’t arrive in England until more than two decades after Gutenberg’s history-making print job in Mainz, Germany. The first book to issue from a press on English soil was The Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres (“The Sayings of the Philosophers”), published by William Caxton in Westminster in 1477. But Caxton was responsible for an earlier first, as well: in about 1475, while living in Belgium, he produced the first printed book in the “englysshe tonge”: Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (“A Collection of the Histories of Troy”), his own translation of a French courtly romance. The Huntington’s edition is unique, being the only known copy to include a depiction of Caxton presenting a copy of the volume to his patron, Margaret of York, the sister of King Edward IV. These two rare books were the centerpieces of the exhibition, which also included early printings of Chaucer, the classics, law books, school texts, and historical romances “extoling the glories of medieval arms and chivalry.”

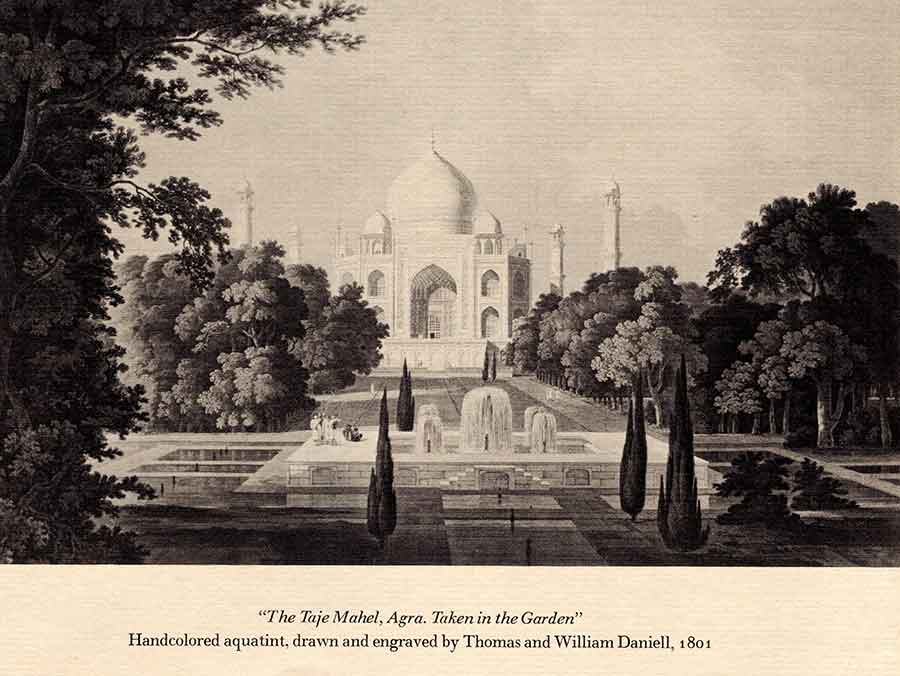

A handcolored aquatint of the Taj Mahal at Agra, India, by Thomas and William Daniell, 1801. Displayed in the exhibition “Handcolored Aquatints by William Daniell” in February 1970. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Watercolors, prints, and drawings from the Art Museum’s collections were another rich source of inspiration for exhibitions, as they still are today. In February of 1970, visitors enjoyed a glimpse at a newly acquired aquatint of India’s breathtaking Taj Mahal by British artists Thomas and William Daniell, produced in 1801. The pair, uncle and nephew, had spent a decade in India, traveling through the country making hundreds of drawings and sketches. Back in England, they published many of these scenes as handcolored aquatints, a type of etching that resembles watercolor paintings. In the days before photography—let alone Instagram—these exquisitely rendered views of exotic locales fascinated the British public, and the market for such prints was brisk. Additional aquatints by the Daniells, including views of London and Windsor Castle, rounded out the exhibition.

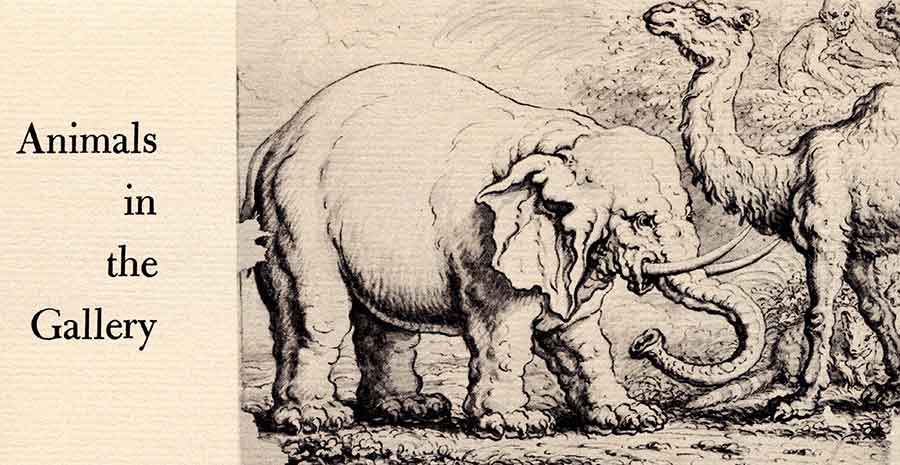

A playful summer exhibition featuring a menagerie of zoological images was described as “the most immediately appealing show to appear on the walls in recent years.” Who could resist a gallery of animals? There was something for everyone: sentimental portraits of dogs by Sir Edwin Landseer; equestrian sketches by John Everett Millais and James Seymour; a bevy of birds, among them an African Grey parrot by Edward Lear; and lion studies by the greatest of 18th-century animal painters, George Stubbs. Perhaps the most memorable creatures in the show were an elephant and camel, captured (along with two monkeys) in a pen and ink study by the 17th-century British illustrator Francis Barlow. As curator Robert Wark noted in the accompanying article: “We doubt if Barlow had in fact seen living examples of either animal. He treats both with an entertaining sense of fancy, particularly evident in the elephant’s toenails.”

Elephant, Camel, and Monkeys, ca. 1663, by Francis Barlow. Pen and brown ink and brush and black ink and wash on laid paper. Seen in the June/July 1970 exhibition “Animals in the Gallery.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Nothing soothes the soul like a walk through a beautiful landscape, and in the 1970s, as today, the Botanical Gardens were both a tranquil oasis for visitors and a teaching tool to promote environmental and cultural awareness. A story about the Australian Garden (a relatively new landscape then, having been established just five years earlier) spotlighted dry-climate plants suitable for home gardens in Southern California. In Henry E. Huntington’s day, the five-acre site had first been a vineyard, and later a grove of oranges. In the 1940s, eucalyptus trees from the U.S. Department of Agriculture were planted to test their viability as timber; most were later removed. In its 1970 incarnation, this “garden down under” boasted showy Acacia baileyana and Callistemon (bottlebrush) trees, whimsical kangaroo paws (Anigozanthus manglesii), and many plants not yet known to local gardeners, such as the profusely flowering Prostanthera (mint bush). These plants may be far more familiar today, thanks in part to The Huntington (and its annual plant sales). Myron Kimnach, the Botanical director at the time, encouraged readers to “stroll through our Australian Garden several times yearly and . . . perhaps you will be inspired to grow more of these plants in your own garden.”

The Australian Garden, featured in a February 1970 story, showcases plants from “down under” that are suitable for Southern California’s climate. This landscape introduced many now-popular plants (such as kangaroo paws) to local gardeners. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

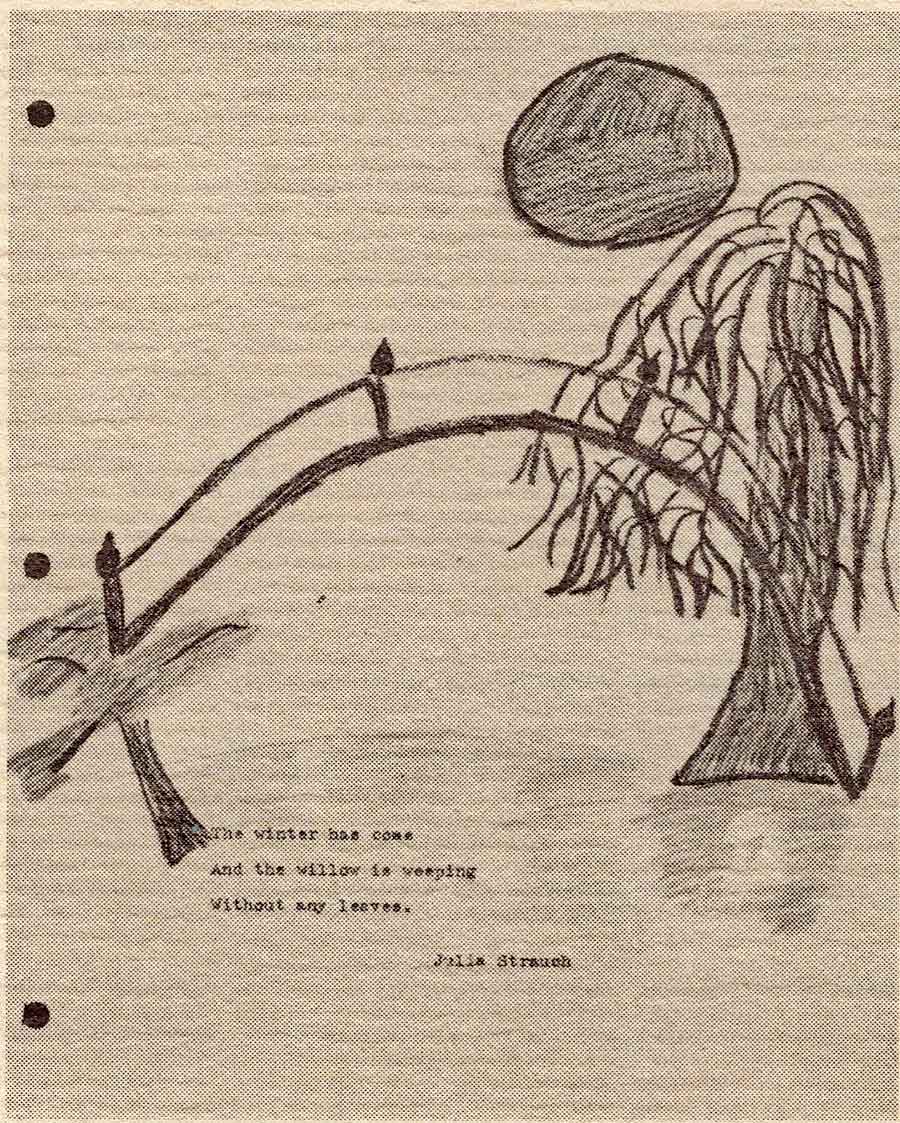

Topping the list of serene spaces at The Huntington is the Japanese Garden. It might surprise the casual visitor to know that this landscape has a long history as a lively, living classroom, having hosted tours for schoolchildren studying Japanese culture since the mid-1960s. Many students sent thank-you notes to their docents, often in the form of haiku poetry and original works of art. The garden has important lessons to impart to adults, as well. In a 1970 story, botanist Fred Boutin wrote: “With today’s increasing interest in the environment, a foreign landscape provides a comparison by which to come to a better understanding of one’s own surroundings . . . [T]he viewer becomes aware that this landscape is guided by a sensitive philosophy where man lives with and manages the environment without subjugating it.”

One of the “blockbuster” events of 1970 was an exhibition in the Library celebrating the bicentennial of poet William Wordsworth’s birth. One gem among the display of letters, manuscript poems, first editions, and other rare items was an account Wordsworth penned of his own birthday celebration in 1844, when he was 74 years young. Held at his home in Grasmere shortly after Easter, the party for local families and friends included a lavish tea of oranges, gingerbread, and painted eggs. Masses of spring daffodils provided the decoration. In a letter to his publisher, Edward Moxon, Wordsworth wrote: “I wish you and yours could have been with us, when upwards of 300 children and half as many adults . . . were entertained in the grounds & House at Rydal Mount. The treat went off delightfully, with music, choral singing, dancing, and chasing each other about in all directions. Young & old, gentle and simple, mingling in everything.”

A fourth-grader’s illustration of the moon bridge in the Japanese Garden, accompanied by a haiku poem, sent as a thank-you after a school visit and published in the October/November 1970 newsletter. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Wordsworth exhibition not only highlighted The Huntington’s important literary holdings but underscored their continuing relevance to scholars and the general public. When asked what college students in 1970 thought of the poet and his work, Paul Zall, professor of English at California State University, Los Angeles, summarized his students’ responses: “Wordsworth’s is a poetry of protest, prophecy, and affirmation. Young people are tuned to his pioneering protests against pollution, war, hunger, population explosion, and urban sprawl. They share his yearning for some rural retreat away from it all where ‘the world is too much with us.’ His muted tones sing of community, of love, of peace and permanence. His poems evoke a quality of experience needed as never before.”

Wordsworth on Helvellyn by Benjamin Robert Heydon, 1842. (The original painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.) The bicentennial of Wordsworth’s birth was the focus of a major Library exhibition in the spring of 1970.

For many scholars, The Huntington itself was a retreat in 1970 from a “world too much with us.” The October/November issue of the Calendar included an essay that recounted how university professors, arriving at the Library to conduct research, were often still reeling from the chaos on their own campuses. One scholar wrote of his time at The Huntington: “What a wonderful way of refreshing the mind and mending the soul after the long months of turmoil.”

The world has changed since 1970, but some things remain the same—even after 50 years.

Lisa Blackburn is senior editor and special projects manager in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington. She has been the editor of Calendar since 2001.