The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Reading the Light in Shigemi Uyeda’s Photography

Posted on Wed., June 24, 2020 by

The photographer Shigemi Uyeda at age 21. Photo by Sadaichi Imada (1885–1952). Courtesy of the Uyeda Family and Dennis Reed.

Nine works by the artist Shigemi Uyeda (1902–1980) are among The Huntington's robust collection of American photography, which is particularly strong in pictures from the first half of the 20th century.

Uyeda was born in Hiroshima, Japan and immigrated to Southern California at age 15 in 1917—two years before Henry and Arabella Huntington announced the creation of The Huntington. He began photographing soon after his arrival and continued honing his skills while settling in Lancaster, working as a day laborer, becoming a husband and father, and eventually establishing his own poultry farm. Though he never lived in Los Angeles, he made frequent trips to the city, becoming part of the vibrant artistic community that coalesced in Little Tokyo between the world wars.

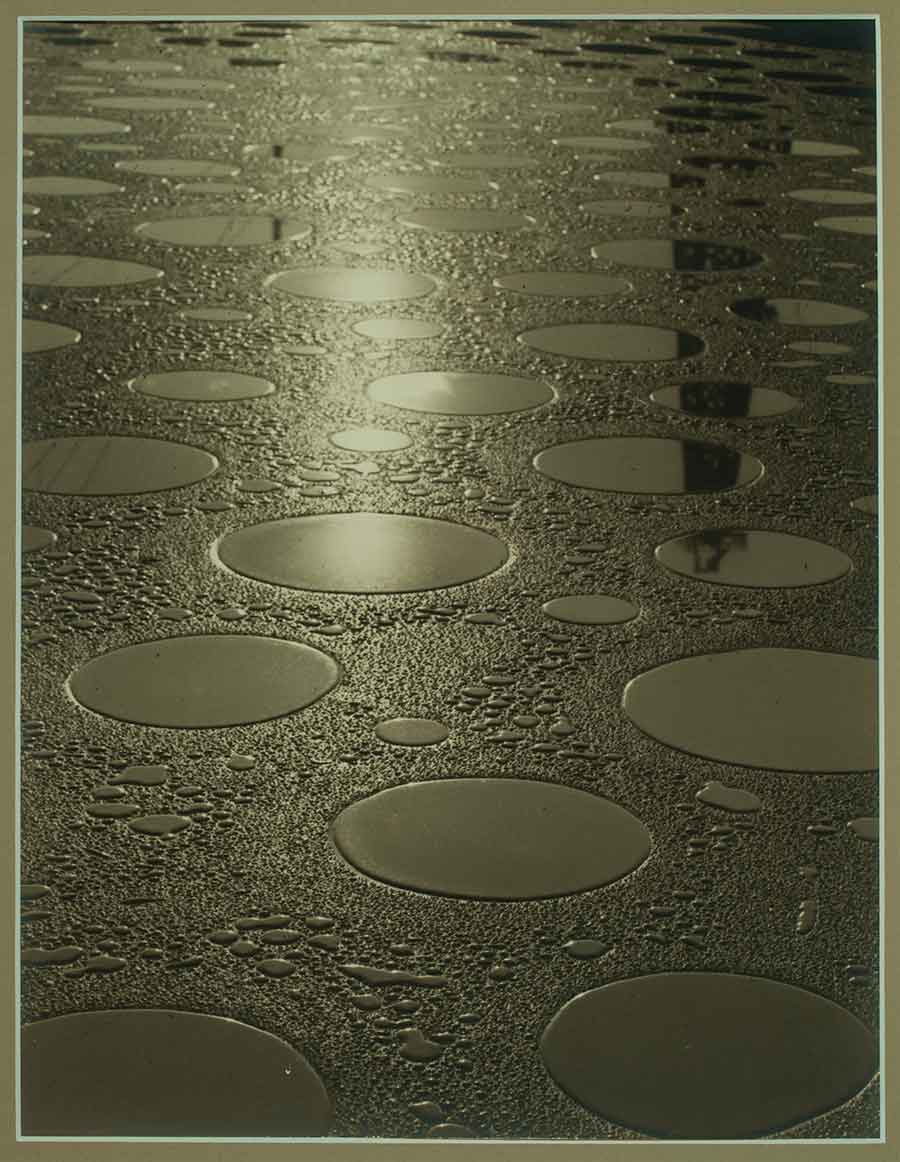

Uyeda’s most well-known photograph is a gelatin silver print, Reflections on the Oil Ditch, made around 1924. It won him first place in a Kodak competition and was published in the late 1920s and 1930s by numerous international and avant-garde art journals. The editors of German Bauhaus magazine The New Vision, Russia’s Soviet Foto, and Britain’s Photogram of the Year liked the picture’s fine details, sharp focus, and reference to modern technology and industry through the oil ditch, its repetitive circles, and the derrick reflected in the upper-right corner. But what about the second reflection invoked by the title: the light raking over the sludge?

Shigemi Uyeda, Reflections on the Oil Ditch, ca. 1924, gelatin silver print, 13 x 10.5 in. Courtesy of the Uyeda Family and Dennis Reed. Uyeda impressed artistic communities at home and abroad with this picture, taken at dawn at an oil ditch in Santa Fe Springs, California. According to the artist, the circles were formed from pools of water sitting on the hardened oil after cold and rain.

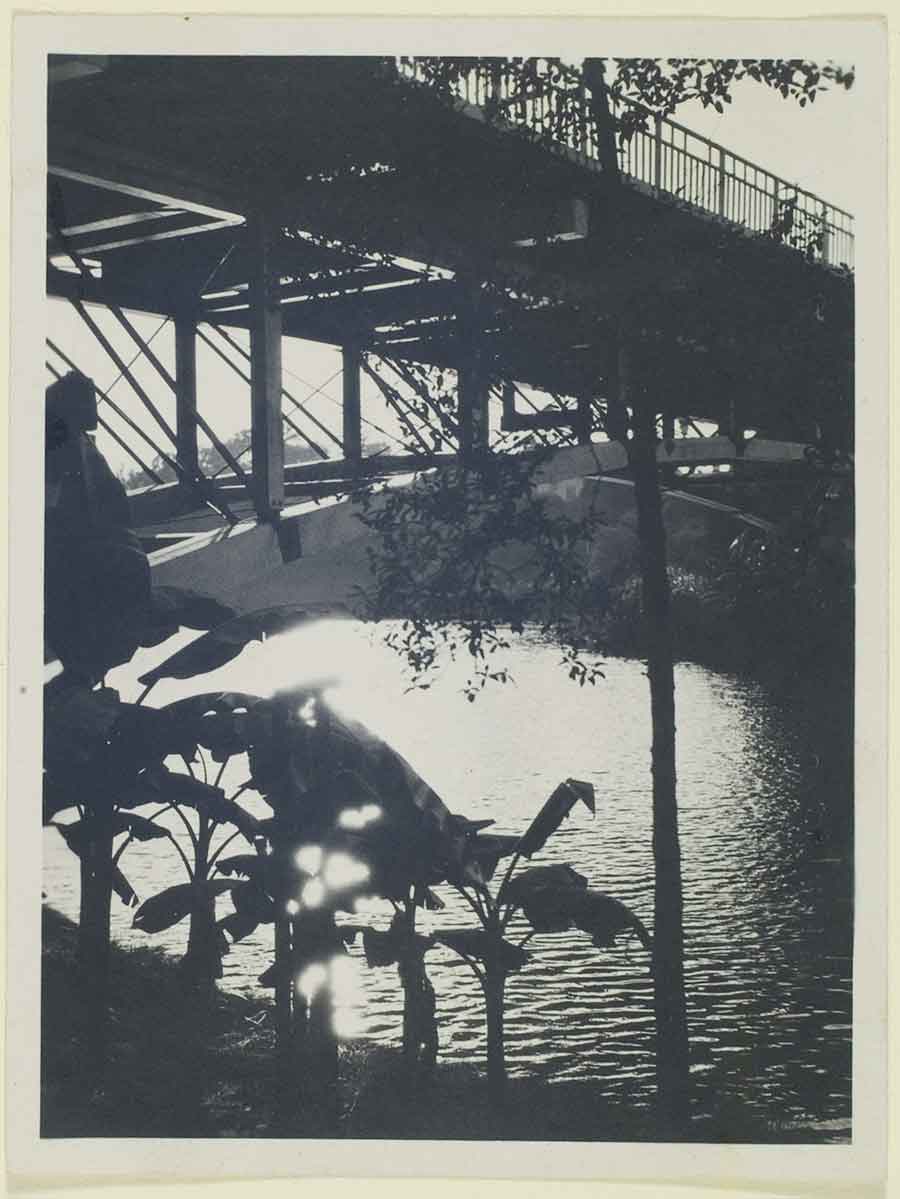

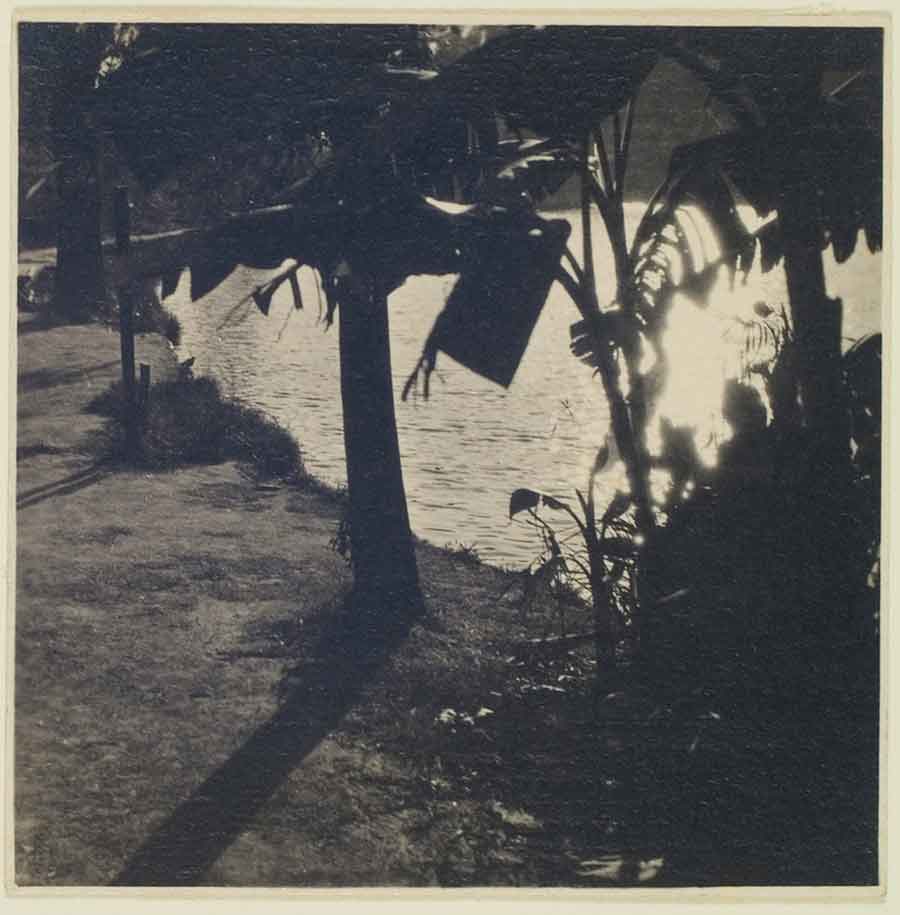

Though noticeable, the light did not strike me as particularly significant the first few times I looked at the photo. But over time, I realized that three of Uyeda’s prints at The Huntington feature similar beams that are even stronger and seemingly less controlled than in Oil Ditch. It remains a mystery if the images—two captured in a park and one on a boat—were ever published or exhibited. However, the fact that the artist printed and originally kept them in a personal album suggests he liked, and actively pursued, the effect. Further evidence of the intentionality of the glare is its careful calibration: Uyeda allowed enough light to catch our attention, yet it does not dominate the photos or prevent us from appreciating the rest of the scene.

Shigemi Uyeda, untitled, 1920–29, gelatin silver contact print, 4.25 x 3.25 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The persistence of a controlled glare in numerous photos by Uyeda suggests he intentionally cultivated the effect.

What might these clearly considered beams have meant to the artist, consciously or not? I personally am reminded of a phenomenon that is as common to those with camera phones today as it was for those with Kodak Brownie cameras in the 1920s: moving the lens into the light and provoking a glare. In Uyeda’s pictures, the beams’ immediacy contrasts with his meticulously coordinated compositions and rendering of much of the world as flat, inky shapes. Through the light, the images become more than landscapes we can admire for their simultaneous picturesque and abstract qualities. They are spaces we seem to inhabit.

Shigemi Uyeda, untitled, 1920–29, gelatin silver contact print, 3.13 x 3.19 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Light lends immediacy to Uyeda’s prints, which are otherwise carefully composed, and in pictures like this, verge on abstraction due to deep shadow.

Yet because the glare evokes the actual process, in addition to the end-product, of photo-making, it also prompts consideration of the artist. Thus, when viewers look at Uyeda’s prints, they behold the scene both as themselves, but also from the perspective of the photographer. The creation of this merging or oscillation between the self and the artist is an empathetic move, whose significance is particularly pointed given the context of inter-war California. When Uyeda made these pictures, first-generation Japanese-Americans (issei) were barred from citizenship, not allowed to own property, and faced many other forms of social, economic, and political racism that culminated in the 1924 Johnson Reed Act (prohibiting immigration from Asian countries) and Executive Order 9066, which forcibly incarcerated people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast from 1942 to 1945. (The California Assembly this past February passed Resolution 77, a formal state apology for carrying out Executive Order 9066.)

Shigemi Uyeda, untitled, 1920–29, gelatin silver contact print, 4 x 3 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Radiant, immersive light evokes the presence and perspective of the photographer alongside that of the viewer.

When we share the views Uyeda captured with his camera, what do we see? The world is beautiful, to be sure, even in ordinary places like the park or wastelands like the oil ditch. But especially in The Huntington photographs, the artist has produced a sense of solitude through the way we observe the park from among the trees—as if from the wings of a stage—or via the vastness of the sea, the empty horizon, and the ship's deck seemingly devoid of people. In the midst of this solitude, sought or imposed, is the light. It insists the photographer was there, and that for a moment, so are we.

Lily Allen is a research associate in American art at The Huntington.