The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

“Release the Vessel & Cargo”

Posted on Wed., June 17, 2020 by

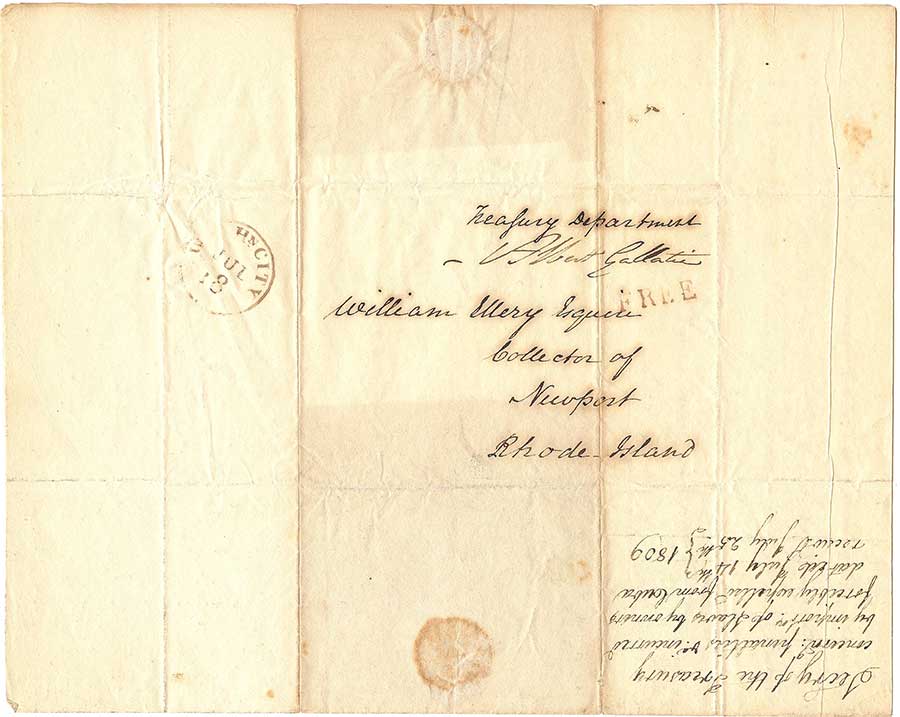

Letter addressed by Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin (1761–1849) to William Ellery (1727–1820), the collector of customs in Newport, Rhode Island, on July 14, 1809. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Last December, The Huntington announced that it had acquired the historical manuscript collection assembled by L. Dennis Shapiro. In addition to a superb group of some 340 rare items ranging from the 18th to the early 20th century, The Huntington received an endowment gift to establish the Shapiro Center for American History and Culture.

The Shapiro collection, which includes letters and manuscripts penned by United States presidents from George Washington to Barack Obama—as well as by their friends, families, advisors, and members of their administrations—is particularly rich in primary sources for historians of the Early Republic. For example, it contains a substantial number of unpublished letters by Albert Alphonse Gallatin (1761–1849), a Swiss-born American politician, diplomat, and scholar who served as the Secretary of the Treasury (1801–1814) under presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

One letter in the Shapiro collection, a seemingly pedestrian communication that Gallatin wrote on July 14, 1809, encapsulates the toxic nexus of race, human bondage, and privilege, and bears witness to the painful and tortuous history of slavery in the United States.

The Constitution (Article 1) gave Congress power to "define and punish" all "Offences against the Law of Nations." International trade in enslaved humans, long condemned as "infernal traffick in human flesh," was one such offense. Yet the Constitution (Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1) banned Congress from imposing any restrictions on this form of human trafficking (delicately described as the "Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit") until 1808.

Congress took up the issue just as the embargo was expiring. On March 2, 1807, Congress passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves. Adopted after years of sustained antislavery campaigning, the Act was greeted as a major victory. African American communities celebrated January 1, 1808, the day when the law took effect, as an alternative to the Fourth of July (much like their descendants would later celebrate Juneteenth to commemorate the order issued on June 19, 1865, by Union General Gordon Granger, to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas).

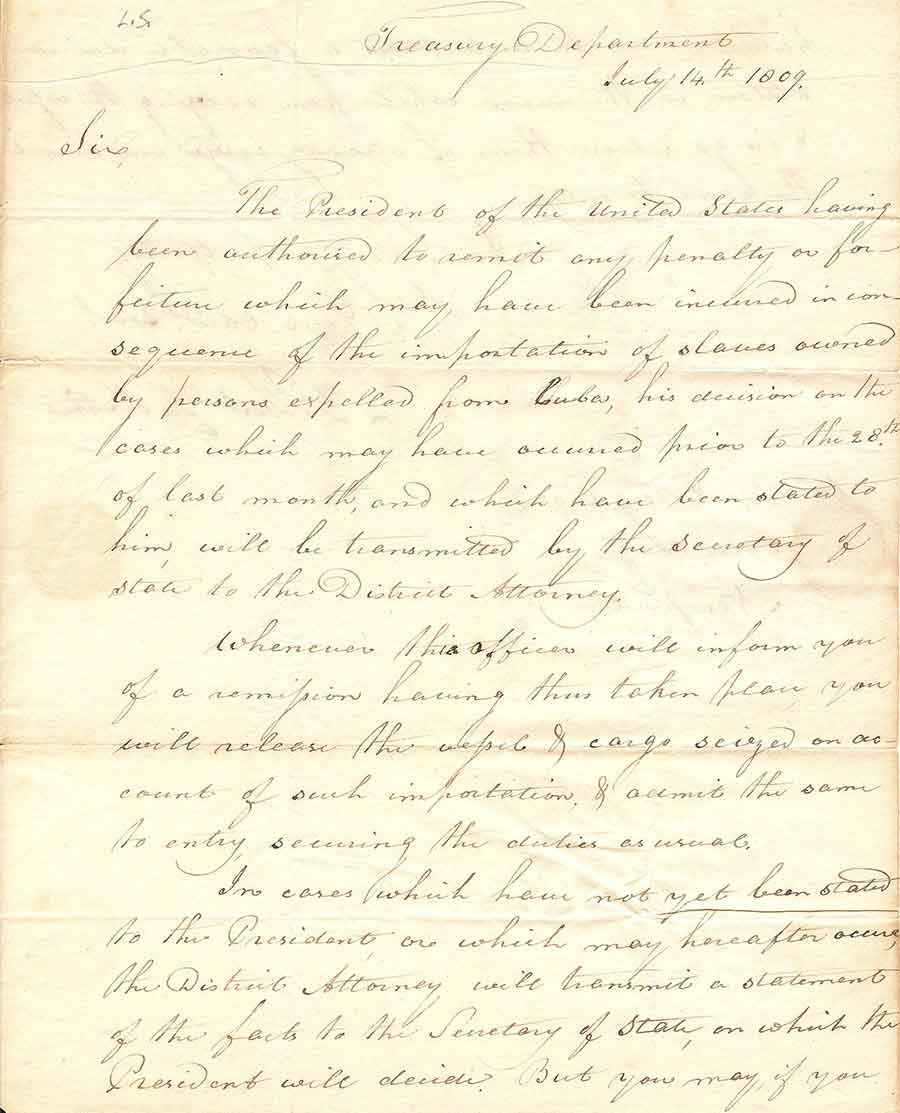

First page of a letter by Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin to William Ellery, the collector of customs in Newport, Rhode Island, dated July 14, 1809. Gallatin, acting on the orders of President James Madison, not only orders Ellery to “release the vessel & cargo” belonging to the “persons expelled from Cuba,” but pointedly instructs him “to anticipate a favorable decision” in all future similar cases and thus “abstain” from any contravening actions. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As seen in Gallatin’s letter, written a little more than a year later, even a straightforward and unequivocal ban on bringing any “negro, mulatto, or person of colour, with intent to hold, sell, or dispose of such [person] as a slave” from “any foreign kingdom, place, or country” was difficult to enforce.

The letter was written four months after the Spanish authorities, in retaliation for Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, expelled French nationals from Cuba. The exiles, many of them slaveowners who had fled the Haitian Revolution of 1791, headed for the United States. The 1807 Act should have barred them from bringing their enslaved “cargo” into the country. Nevertheless, in May 1809, President James Madison permitted roughly 100 Cuban French to do just that. On June 28, 1809, Congress gave the formal sanction to Madison’s executive decision, authorizing the president “to release all vessels and other effects” that had already been seized and use federal funds to “remit any penalty or forfeiture” imposed on the slaveholders. This new presidential prerogative is the subject of Gallatin’s letter.

The Secretary of the Treasury was most likely aware that his addressee, William Ellery (1727–1820)—a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the customs officer of Newport, Rhode Island—was a vocal opponent of slavery. In 1785, Ellery, as the Rhode Island representative in the Congress of Confederation, sponsored a motion that would have inserted a strong antislavery clause in the Land Ordinance. (The motion failed.) Appointed by George Washington to the post of customs collector of Newport in 1790, Ellery quickly became the inveterate enemy of Rhode Island slave traders, including the powerful James DeWolf.

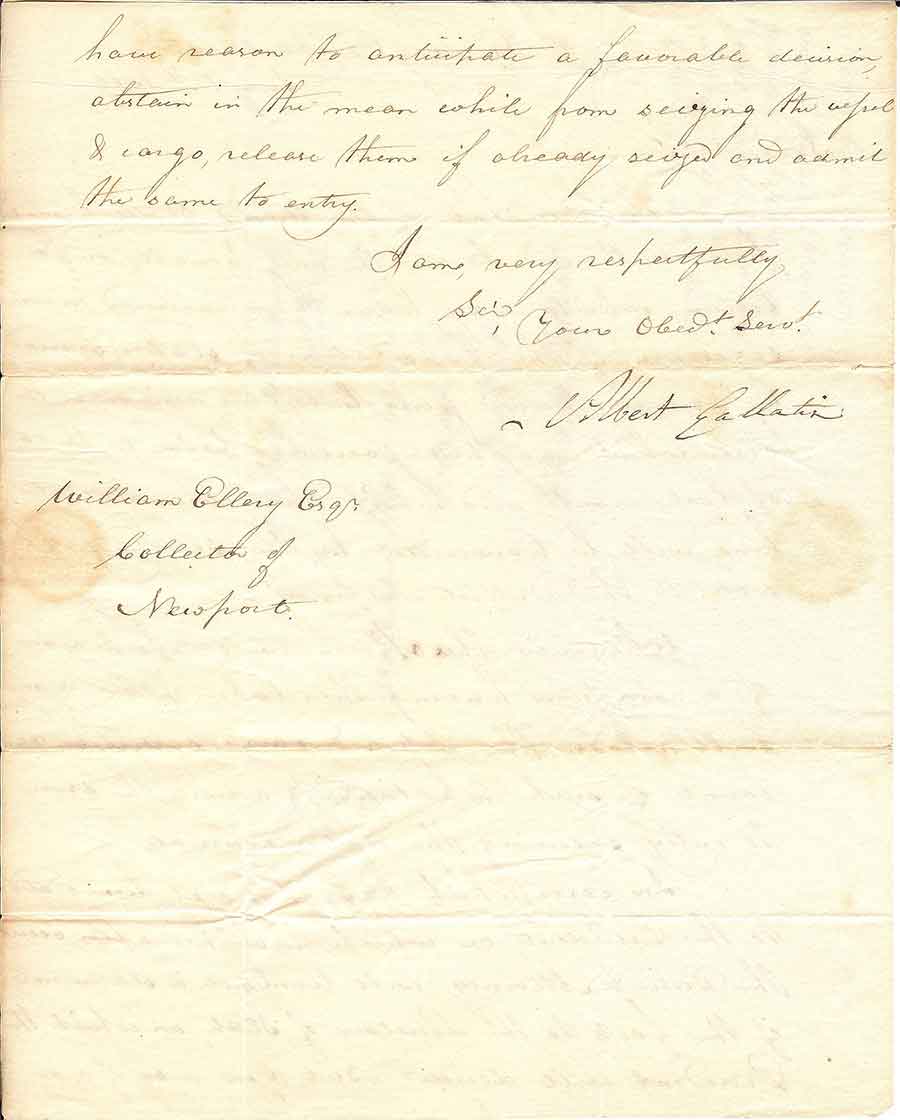

In 1809, Ellery, no doubt relishing his authority to enforce the antislavery law, had immediately seized the ships bearing the enslaved people belonging to “persons expelled from Cuba.” Ellery’s boss, Gallatin, who served at the pleasure of the president, not only ordered Ellery in the letter to “release the vessel & cargo” but pointedly instructed him “to anticipate a favorable decision” in all future similar cases and thus “abstain” from actions mandated by the 1807 Act.

Ellery must have been livid. Allowed to bring their human “property” into the United States, the Cuban slaveowners would soon transport their “cargo” to New Orleans, nearly doubling the population of the city.

Second page of a letter by Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin to William Ellery, the collector of customs in Newport, Rhode Island, July 14, 1809, showing Gallatin’s signature. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In the coming years, Ellery would repeatedly appeal to Gallatin for a naval force to be stationed in Rhode Island to combat the slave trade. Unsurprisingly, no such force ever materialized. In 1819, the 92-year-old Ellery might have taken heart in the law that qualified international trade in enslaved people as piracy, a federal crime punishable by death.

If the new law made Ellery optimistic, then future events would have disillusioned him. One can only hope that when he died a year later, in 1820, he did not know that his nephew Christopher Ellery, a Rhode Island proslavery politician with close ties to DeWolf, would succeed him in his post as customs collector of Newport. Slave ships bound for the United States would continue to cross the Atlantic, and with the 1807 Act barely enforced, the perpetrators knew that, even if caught, they would get off with a slap on the wrist.

In the 1850s, a campaign to repeal the ban on the transatlantic slave trade gathered momentum, finding sympathizers in Congress. It had become painfully obvious that the ban on bringing enslaved laborers from abroad was essentially meaningless in a country where the buying and selling of enslaved men, women, and children remained perfectly legal and highly profitable.

In 1860, the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States (its remains were discovered last year), was allowed to complete its awful journey, unimpeded, all the way from West Africa into Alabama’s Mobile Bay—a sad epilogue to the story that unfolds in Gallatin’s letter.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.