The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Resurgence of Victory Gardens

Posted on Wed., July 1, 2020 by

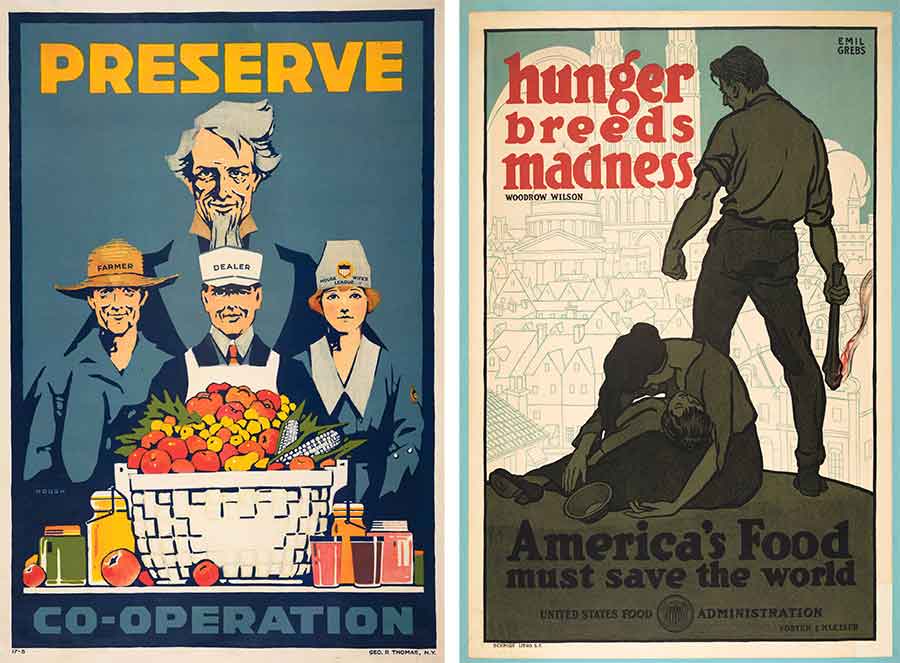

Carter Housh, Preserve Co-Operation, 1917 (left) and Emil Grebs, Hunger Breeds Madness, 1918. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Posters encouraging the growing and preservation of food were disseminated during both World War I and II. Carter Housh designed five Preserve posters for the National Commercial Gas Association; these were distributed by gas companies in over 200 cities.

In an effort to increase self-sufficiency and reduce trips to the grocery store during our current pandemic, a growing number of people are adding vegetable and herb gardens to their own yards. It's a trend reminiscent of the American victory gardens planted by the millions during World War I and II to offset food shortages and boost morale.

The war garden movement is well documented in The Huntington’s collections through photographs of these “defense gardens for food,” as they were sometimes called, and through vivid propaganda posters that urged civilians to join the patriotic war effort by planting and preserving their own fruits and vegetables so that food from farms and factories could be shipped to Allied citizens and soldiers.

While amateur gardeners learned how to cultivate crops by reading government-sponsored instruction pamphlets, “propaganda posters, created by a volunteer army of accomplished illustrators, sold the war garden movement to citizens by means of national campaigns,” said David H. Mihaly, The Jay T. Last Curator of Graphic Arts and Social History at The Huntington. “Striking designs and compelling slogans inspired gardeners of all ages to ‘sow the seeds of victory,’ ‘help Hoover in our school gardens,’ and ‘can all you can.’”

“As tools of influence, these posters helped nations justify the war and convince citizens to take action,” Mihaly said. “As works of art, they tell a history of two of the most robust and politically charged periods of poster design.”

Chamomile (left) and chives (right) growing in The Huntington’s Herb Garden. These herbs are not only useful in the kitchen, but also add lovely flowers to any garden space. Photos by Kelly Fernandez.

Mihaly noted that the gardens did not just serve to provide food; they also improved morale on the home front by showing individuals and families that they were not powerless and could indeed help the war effort. Huntington gardeners say home gardens today can serve similar purposes—providing healthy, fresh produce while helping to soothe frayed nerves—as we anxiously grapple with the continued impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I think gardening is a calming force. Our imaginations can run with what-ifs and worries, but when we are actively working with our hands, the worries seem to melt away,” said Cara Hanstein, head gardener of The Huntington’s Ranch Garden, an urban agricultural project filled with edible landscapes. “Gardening is about hope and being forward thinking. You are thinking about the future when you plant a seed. That can sustain us in difficult times.”

Kelly Fernandez, head gardener of The Huntington’s Herb and Shakespeare gardens, said planting herbs can be especially useful now; herbs can be steeped to make calming teas, and the scents of lemon balm, lemon verbena, and lavender can soothe and refresh. Fernandez, who earned a certificate in horticultural therapy from the Chicago Botanic Garden in 2015, noted that the act of gardening can itself be healing.

“Gardening is a living, breathing experience that can simultaneously stimulate your senses and relax your mind,” said Fernandez. “That’s important in a time when we all need to be easy on ourselves.”

Many vegetables, including these cabbages, have been growing well in Huntington gardens throughout the recent closure. Several truckloads of vegetables have been donated to a local food bank. Photo by Cara Hanstein.

Anastasia Day—a graduate student in history and a Hagley Scholar in the history of capitalism, technology, and culture at the University of Delaware—is one of the few researchers who has looked deeply into the origins of victory gardens. (Like many of us, Day is personally affected by the pandemic; her upcoming dissertation defense will be held via a video conference.)

Day sees many connections to the current pandemic, from a run on seeds during World War II that mirrors seed shortages seen today, to the heavy reliance on war metaphors in posters and discussions. “The most visible imagery of the victory garden was military,” Day said. “That’s obviously linked to the coronavirus of today. People are using the metaphor that this is a war.” The motivations for today’s garden are also similar. “There’s the idea that by providing for yourself, you’re providing for the nation,” she said.

For years, Day has used a search engine alert system to receive notifications of any mention of victory gardens online. Since the pandemic started, she’s been getting a lot of alerts. “It’s just been flooded,” Day said. “Prior to this, alerts usually only popped up in obituaries. People often mention that they really enjoyed victory gardening during World War II.”

While the notion of victory gardens usually conjures up nostalgic and patriotic visions, Day’s research is shattering many of the myths and tropes that surround victory gardens and their origins. One of Day’s main findings is that the gardens were not a grassroots effort that sprung up to aid the war effort, but rather were part of a campaign orchestrated by corporations and the government to promote and protect major industries and the capitalist economy.

These vivid dragon carrots are an example of the many unique varieties of vegetables that can be difficult to find in stores but can be grown in home gardens. Photo by Cara Hanstein.

“This was not bottom-up, but a colossal top-down effort,” she said. “This packaged a lot of corporate agendas. Green Giant couldn’t sell food, but they could advertise how to grow food and, in that way, keep their brand consciousness in the public mind.”

Many posters depicted children, some happily pushing plows, as they worked in the Bureau of Education’s U.S. School Garden Army as “soldiers of the soil.” In reality, Day said, her research showed that the program resulted in children from schools in minority communities being bussed to work in fields to grow food for school lunches. “It wasn’t considered child labor because it looked healthful,” Day said. “What could be more healthful than gardening?”

Day’s research also revealed that the victory garden trend didn’t last after the war ended. “People got their seeds ready, they got their tools ready, they got their plots, and then they discovered gardening is a lot of work and is not always fun,” Day said, noting that a similar pandemic trend, baking sourdough bread at home, seems to be similarly fizzling out. “My prediction is this summer, a lot of people are also going to realize this. It’s a lot of work and plants don’t grow themselves.”

Burt E. Woodburn tending a victory garden during World War II. The Southern California Edison Photographs and Negatives Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Hanstein and Fernandez both hope that the new gardens being planted will be a more lasting trend, especially in Southern California, where vegetables and herbs are easy to grow year-round. Even if the gardening impulse turns out to be short term, gardeners say the benefits of growing food, herbs, and flowers during this crisis are immense.

“Everything is all about self-sufficiency right now,” Hanstein said. “To learn that you can grow your own food can really give you confidence.”

Hanstein added that home gardening is also a great activity to enjoy with kids who have been tucked inside spending too much time on screens. Children of all ages can plant and water seeds, and older kids can also learn about the history of victory gardens, she said. “Children love getting dirty and working with their hands, and it’s a great opportunity to get them fresh air after being cooped up inside,” said Hanstein, who recommended pole beans, corn, and carrots as great plants to start from seed with youngsters.

For this time of year, Hanstein recommends growing tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, beans, carrots, and basil. She also encourages adding lots of compost and planting flowers for pollination and beauty. Plant starts are available for curbside pickup from many garden stores, and seeds are now becoming available again. (Even Hanstein had trouble obtaining seeds at the start of the pandemic, when seeds from her usual suppliers were all backordered.)

P. V. Moffat and F. V. Lucas plowing a victory garden in Montebello, California, in 1944. The Southern California Edison Photographs and Negatives Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Gardening at home also offers the chance to share your bounty with friends and neighbors, something The Huntington has been doing in recent weeks. Several truckloads of vegetables, including kale, Swiss chard, carrots, and brussels sprouts grown in the gardens, have been taken to Friends In Deed, an Altadena food bank, since the shutdown began. “They really appreciated getting the fresh produce,” Hanstein said.

While Day’s deep probe into victory gardens has left her with a sobering view of their origins, she does see the positive impact that they had, and that new food gardens could have now. Many victory gardens during World War II, for example, were grown by new urbanites who had lost their connections to the land. “In victory gardens at hospitals, you had recovering soldiers gardening who had grown up in a city, were 26 years old, and didn’t know a radish came out of the ground,” she said. “When people victory gardened, they were interacting with the earth in a way they never had before. So many people had gotten out of touch with where food comes from, and what being outdoors was like.”

Although victory gardens were transient, Day said, they did leave a permanent cultural mark on the nation, as well as an indelible imprint on the country’s landscaping. She believes the gardens sowed the seeds of the modern environmental movement and also impacted the evolution of the suburban yard. It could be that today’s pandemic gardens will leave an important mark as well, Day said, but only if attention is paid to deeper structural problems and inequities in the nation’s food system, including the lack of support for local farmers, the lack of concern about farmworkers’ health, and the lack of fresh food for many inner-city minority communities.

“For this to succeed,” she said, “people need to make larger connections and see this gardening movement as a contribution to community health.”

Usha Lee McFarling is senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.