The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Spines, Thorns, and Prickles

Posted on Wed., July 22, 2020 by

The stem of Alluaudia ascendens, in the Desert Garden, showing multiple sharp thorns. This species makes up a core component of the spiny thicket forests in southern Madagascar. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

When you walk among the living plant collections at The Huntington, especially in the Desert Garden, you may notice that many of the plants have spines. Although it has been shown that in some plant families, such as cacti, spines arose primarily as a mechanism to reduce water loss from leaves, most plants that have spines use them to protect themselves from hungry animals. This development of true spines and spine-like structures like thorns and prickles is a recurring adaptation seen in plants from around the world. Botanists like myself describe such plants as spinescent.

To a botanist, however, not all spiny structures are the same. It turns out that spines are derived from leaf tissue and thorns from stem tissue. Prickles come from neither; they are simply corky projections from a plant’s skin, or dermal tissue. Plant anatomy comes into play here, as the internal structure of leaves, stems, and roots are unique in their arrangement.

Unlike many thorns, which are strong because they are woody, the thorn of Alluaudia ascendens has a strong, corky shield made of dermal tissue that can be pried off to reveal a soft green thorn underneath. Video by Sean Lahmeyer.

Until recently, I did not view our plant collections through the lens of “spinescence.” But the more I have, the more I’ve realized our gardens provide an ideal setting for exploring this subject in more detail. At The Huntington, we have one of the largest living plant collections in the nation, with diverse plants from around the world growing in assemblages that you would never see in the wild. And quite a few of them have spines.

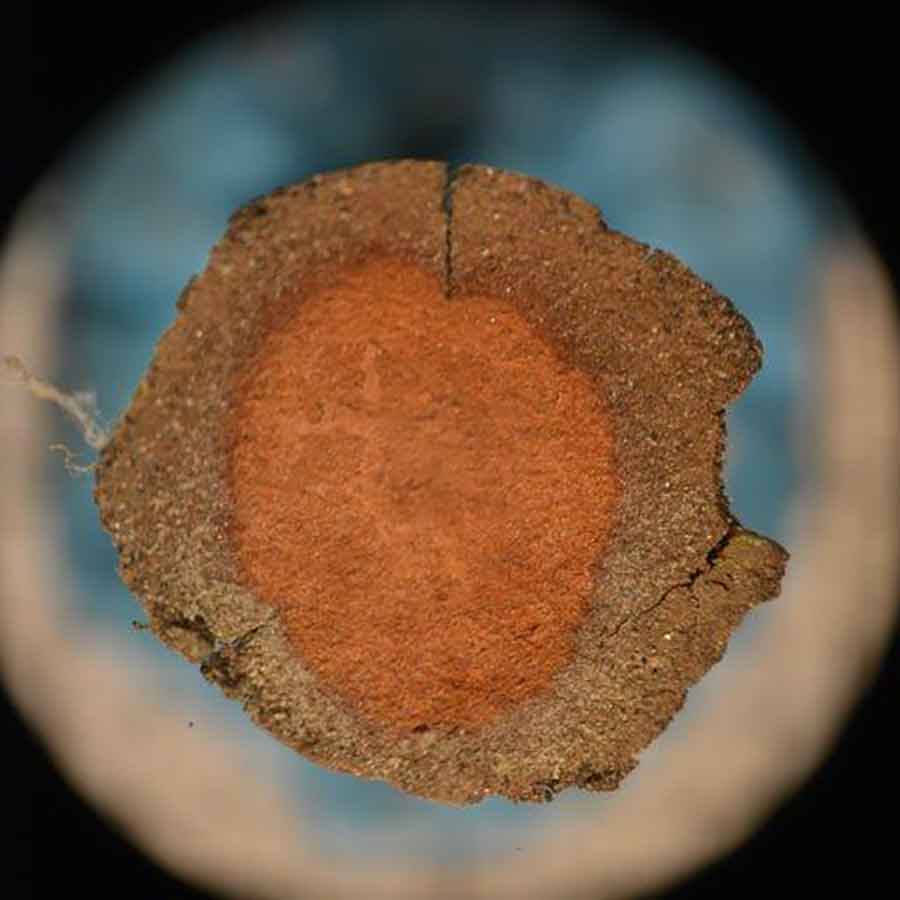

Cross section of an Alluaudia ascendens thorn, with the addition of methylene blue dye for contrast. The internal anatomy matches that of a stem. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

A query of our collection database for the names of plants that have spiny epithets as part of their scientific names—such as “Acanth-,” which is Greek for “spine,” or “Acut-,” which is Latin for “sharp”—reveals that nearly 3,500 plants in our collection have something spiny of note.

Equipped with a good razor blade, a microscope, and some dye to stain plant tissue, I was able to make cross sections of many of these spiny structures. What I saw was both beautiful and instructive: Spines, thorns, and prickles are surprisingly different structures, even though they all serve a similar purpose.

The stem of Ceiba insignis (silk floss tree), in the Desert Garden, showing bark with prickles. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

Spines, the ones derived from leaves, show many variations worthy of note. Some spines, like those in the Fouquieria family (think of an Ocotillo plant from the Mojave Desert), are derived from leaf stalks. Acacia trees (in the bean family) have spines made of modified leaf stipules. There are also plants whose entire leaves have been converted into spines, as is the case with cacti. All of these spines are dead at maturity, full of fibers, and no longer capable of photosynthesis.

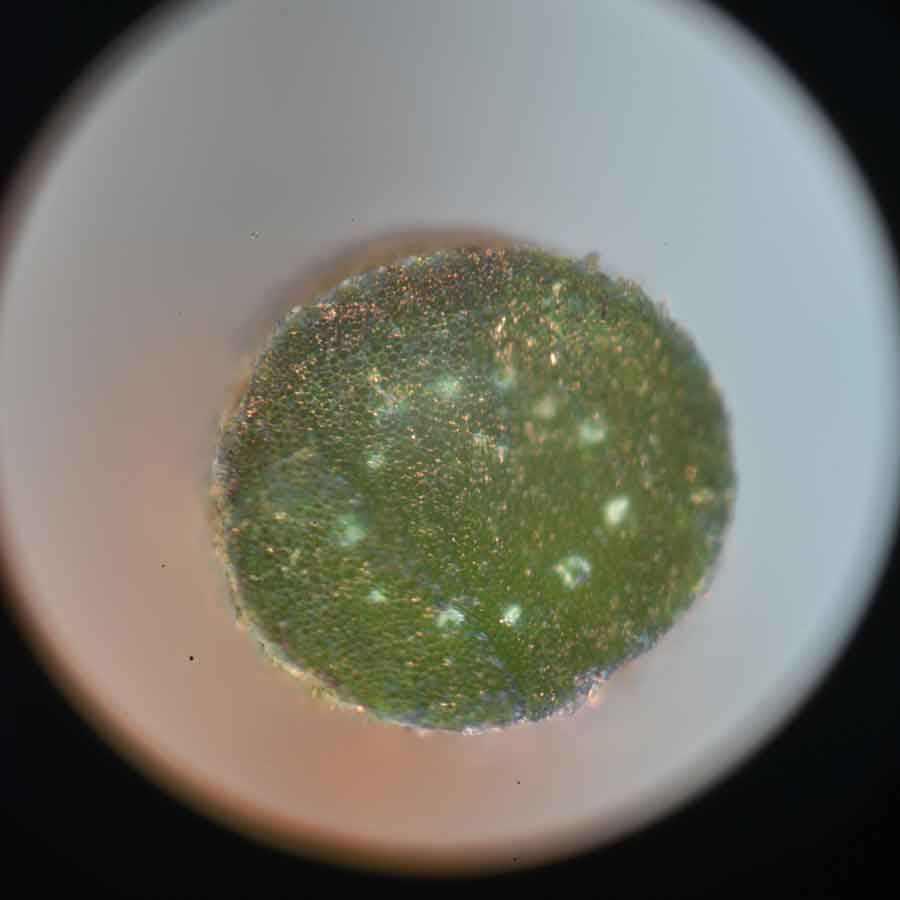

Cross section of a prickle from a Ceiba insignis (silk floss tree). The entire structure is made up of rigid dermal tissue and is devoid of any characteristics of a leaf, stem, or root. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

In The Huntington’s gardens, there are more plants with thorns than spines. Many plants convert a woody stem into a thorn, and many unrelated plant families share this adaptation, including hawthorn (Crataegus) in the rose family, Citrus in the rue family, and Natal plum (Carissa) in the dogbane family.

I found one notable exception in Alluaudia, a group of spiny trees endemic to Madagascar. Their thorns have a hardened outer dermal layer, instead of a stronger internal core, such as wood would provide. A comparison can be drawn to the hard coating, or exoskeleton, of an insect versus the bone, or endoskeleton, of a vertebrate animal—they are both adaptations for structural strength.

The stem of a tropical palm, Cryosophila albida, showing root spines along its trunk. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

Prickles are notable for their complete absence of vascular tissue, the microscopic vessels that conduct sugar and water throughout a plant. Since prickles are sharp projections produced by the skin of a plant, they tend to pop off easily, as they do on rose bushes. (That’s right, roses have prickles, not thorns!) The prickles on the silk floss tree (Ceiba insignis) in the Desert Garden give this tree one of the most handsome trunks in our collection.

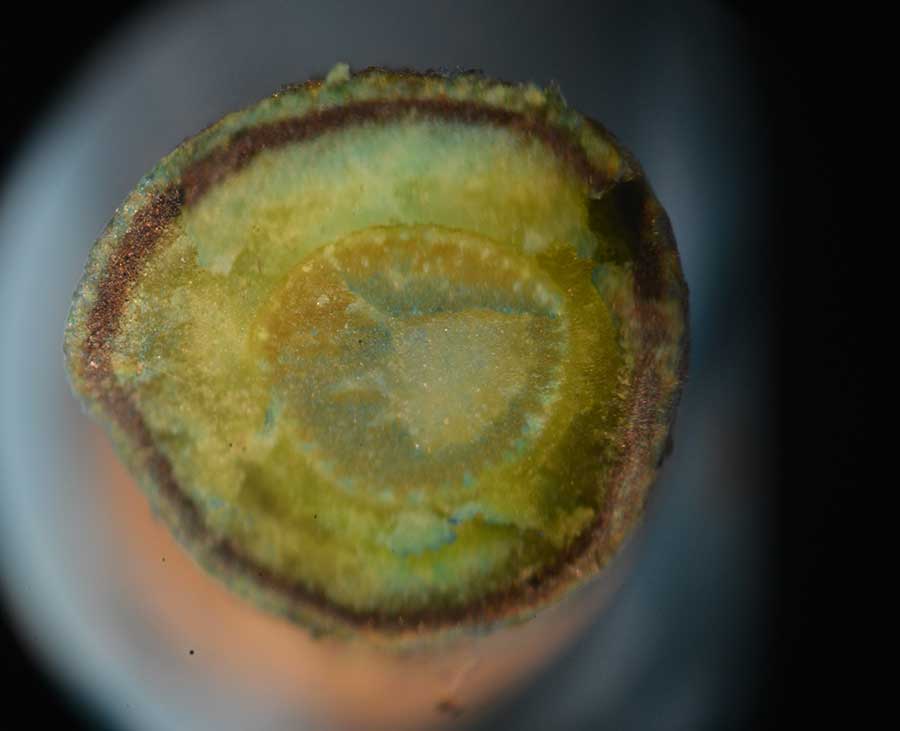

Perhaps the most intriguing example of spinescence can be found on the trunk of the tropical palm Cryosophila albida in The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science. The palm family is known for having stems and leaves with spiny structures, but there are few examples of palms that produce their shoot spines with root tissue. Indeed, a closer look under the microscope confirmed that the spiny structures on the stem of Cryosophila albida have the internal anatomy of a root, not a stem.

Cross section of a Cryosophila albida root spine, with the addition of methylene blue dye for contrast. The internal anatomy matches that of a root, not a stem. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

So, next time you visit The Huntington, keep an eye out for the spiny, thorny, and prickly projections that serve as defenses for so many of our plants. It’s yet another way to enjoy the marvelous diversity that can be found in the botanical world.

Sean Lahmeyer is the collections and conservation manager in the botanical division at The Huntington.