The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

California Gold Rush Landscapes

Posted on Wed., Aug. 19, 2020

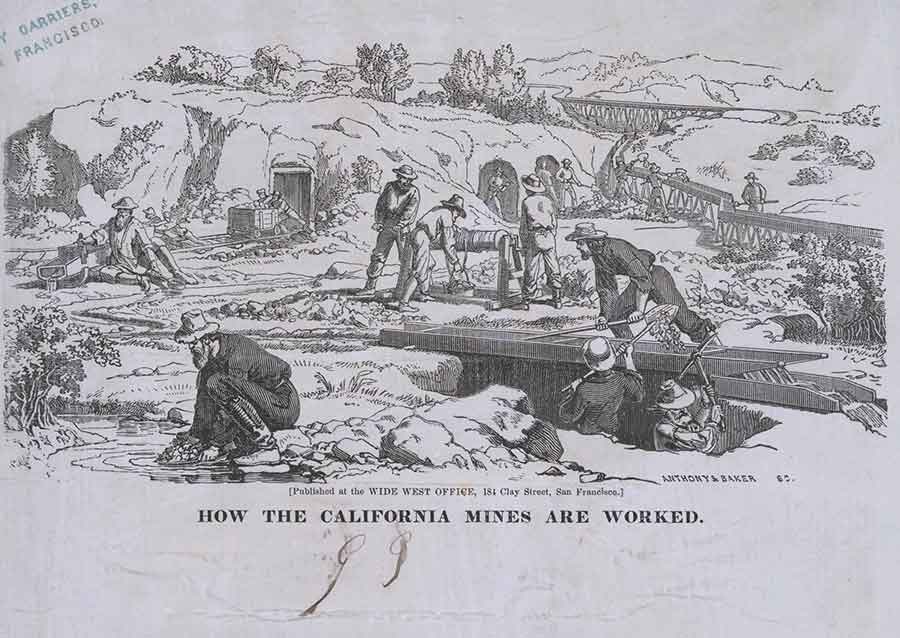

The letter sheets that depicted gold mining in all its permutations emphasized certain common features that characterized that occupation throughout its early years. Above all, they highlighted the staggering amount of physical labor required. Even the simplest means of mining demanded constant bending, shoveling, hauling, and pulling to extract even the tiniest amount of precious metal, leading many miners to compare themselves wryly or bitterly to ditch diggers and brick layers as they suffered aches and pains and illnesses they had never associated with fortune hunting. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In January of 1851, John R. Fitch, a gold prospector, penned these words to his brother: "The wear and tear of the mines is very great." He intended to convey the overwhelming exhaustion felt by many who toiled for gold in California. As seen in the visual record of the gold rush era, however, the labor required to unearth that precious metal exerted considerable wear and tear on the landscapes of California as well.

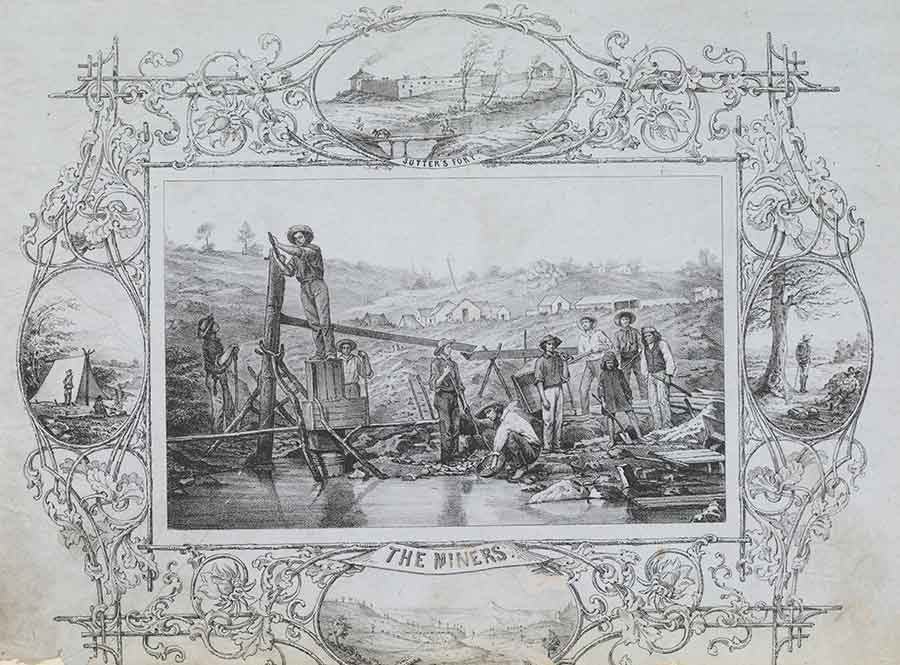

Gold was discovered along the American River, approximately 50 miles from present-day Sacramento, on Jan. 24, 1848. Within a year, thousands of gold seekers from many corners of North and South America stampeded into the gullies and canyons of the Sierra Nevada. Amateurs all, they soon grasped how the rushing water that filled the region’s creeks, streams, and rivers every winter and spring had carved away at the surrounding heights over great stretches of time. Experimenting with the accumulated debris brought down from mountain slopes, they learned that water swirled in metal pans containing shovelfuls of sand and gravel would carry away the refuse and leave behind weightier flakes of gold.

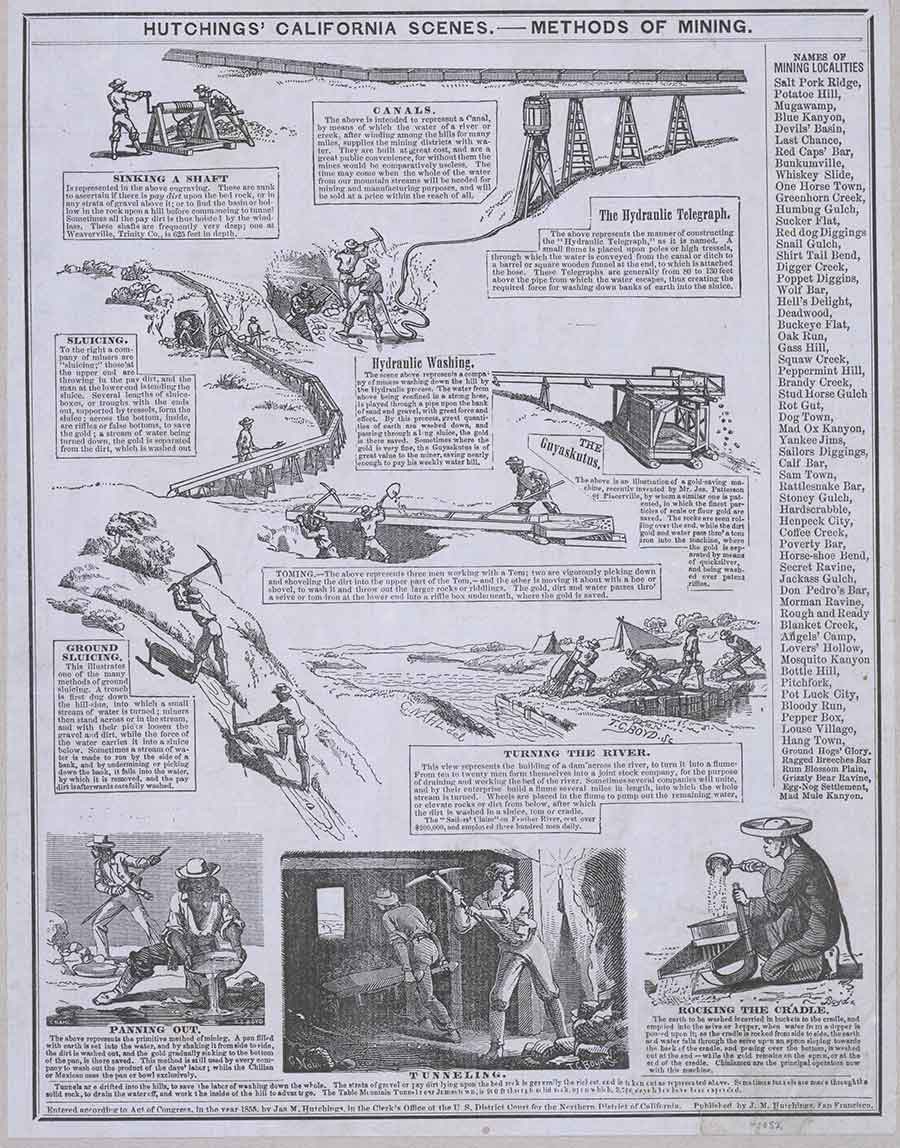

Having to excavate ever more dirt to increase their golden returns, miners during the 1850s developed increasingly sophisticated techniques that would allow the labor of one person to achieve what had once required the labor of two or five or ten. Thousands fortune seekers, drawn to California from all corners of the globe, kept peeling back layers of the earth’s surface in search of gold, including the Chilean and Chinese miners depicted in the lower left- and right-hand corners of this letter sheet. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Thousands of additional fortune seekers arrived every month, and efforts to gouge out gold-bearing soil reached a frenzied pace from 1849 to 1851. Steadily exhausting the most easily accessible gold deposits, these jostling hordes scoured ever wider swaths of the Sierra Nevada range for untapped treasure. In doing so, they also devised new methods and new tools to augment their pursuit of golden rewards. To preserve a record of their struggles, trumpet their individual or collective ingenuity, or demonstrate to their loved ones what the search for gold entailed, many of these treasure hunters wrote lengthy accounts of their exploits in letters home. Their words were often supplemented with the striking imagery of the so-called pictorial letter sheet, another innovation sparked by the rush for gold.

Hoping to capitalize on every miner’s desire to share news of life in California with friends and loved ones, various entrepreneurs in the fields of printing and publishing commissioned individuals skilled with pencil, pen, or brush to capture different aspects of life in the Golden State. Engravers and lithographers then copied the original images onto wood or stone surfaces used in printing presses to duplicate copies by the hundreds or thousands. Reproduced on sheets of paper as large as 11 by 17 inches and then folded in half, the resulting items were sold as illustrated stationery.

Building upon the success of such hand-operated devices as the cradle and the rocker in “washing” tiny scraps of gold out of mounds of dirt, some miners recruited laborers, such as this group of Euro-Americans and Native Americans, to erect lengthy wooden chutes, known as “sluices.” Racing downhill through the sluices, water diverted from creeks, streams, or rivers would wash away mounds of earth shoveled into the water’s course, leaving behind the golden scraps. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The proliferation of the letter sheet, driven in large measure by the explosive growth of California’s gold-seeking population, yielded a dizzying array of subjects geared toward an equally diverse array of tastes and interests. As evidenced by the nearly 200 individual examples of letter sheets posted on the Huntington Digital Library , this stationery captured the news of the day in views of fires, shipwrecks, elections, and public celebrations. Letter sheets memorialized the near-instantaneous growth of California’s cities, towns, and gold camps from San Francisco to Sacramento, and from Marysville to Sonora. They satirized the hardscrabble existence of miners and portrayed the wilderness surroundings where the miners resided. They also reflected somberly or wistfully on the separations from friends and loved ones that miners had to endure.

Other examples, produced in the early years of the gold rush, chronicled the evolution of mining methods and, through them, portrayed how mining would ravage many California landscapes.

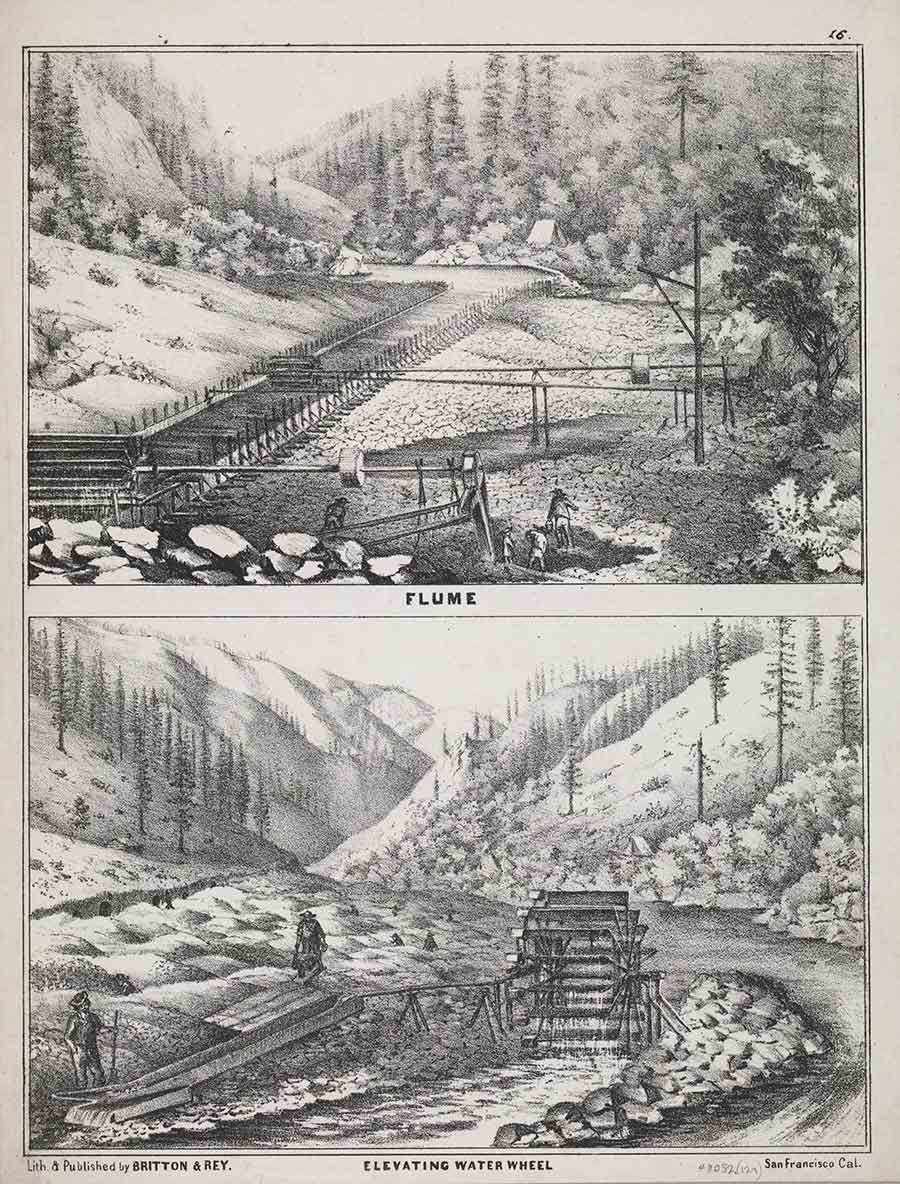

Elaborating upon the application of running water to gold-bearing soil, some ambitious miners constructed large wooden channels, known as “flumes,” to carry great quantities of water to gold mining sites. Surging through those artificial waterways with great force, the resulting torrents spun wheels, turned axles, and ran pulleys to replace muscle power with its mechanical equivalent. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

By the middle of the 1850s, the quest for gold had become the driving force behind the devastation of great tracts of California’s landscapes. Huge patches of riverbanks and hillsides had been torn open and the soil fed into rockers, cradles, sluices, and canals in hopes that it would be washed down to golden particles. Entire forests were cut down to stumps, supplying the lumber required for flumes, water wheels, coffer dams, and underground shoring—the essential infrastructure of industrial-scale mining.

Such structures crisscrossed ridges, gorges, meadows, forests, and rivers, ripping artificial paths through the topography. High-pressured jets of water stripped bare whole mountain slopes and propelled torrents of silt and refuse into the rivers that flowed west out of the Sierra Nevada. Once arable districts downstream from the mountains were buried beneath deep layers of debris, and once navigable rivers were clogged with the same remains. Toxic mercury, used in many locations to amalgamate with gold and remove it from mixtures of minerals, leached out of cradles, rockers, sluices, and flumes to contaminate waterways and farmlands.

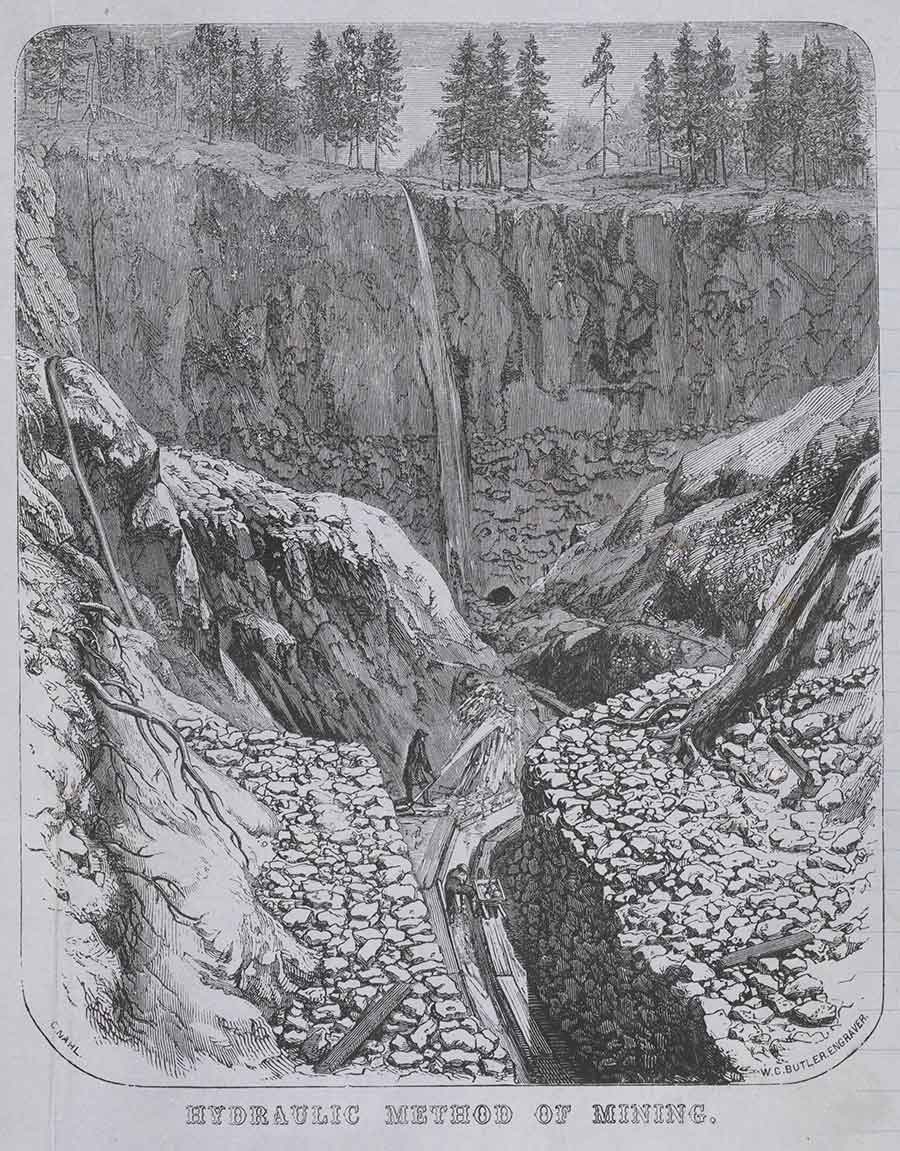

Perhaps the most significant innovation proved to be the procedure known as “hydraulic mining.” Directed into increasingly narrow channels, then forced into canvas hoses, and finally released through iron nozzles, high-pressure jets of water blasted away entire hillsides, washing tons of earth in a day through wooden sluices that captured the fragmentary remains of gold deposits. The resulting massive debris flows, however, choked waterways and obliterated farmlands for decades. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

While such destructive practices continued to take a toll on California’s landscapes, the growing significance of agriculture, commerce, and industrial manufacturing eroded mining’s importance to the Golden State’s economy during the 1860s and 1870s. Abandoned gold camps deteriorated into ghost towns and obsolete infrastructure succumbed to the elements. Second- and third-growth forests reclaimed terrain once cut bare by lumberjacks. By the 1880s, as the balance of political power shifted from miners to farmers, the last great holdout, hydraulic mining, fell under the regulatory power of the courts. The gradual disappearance in subsequent decades of mining’s most visible scars seemed to mark the steady recovery of California’s gold country.

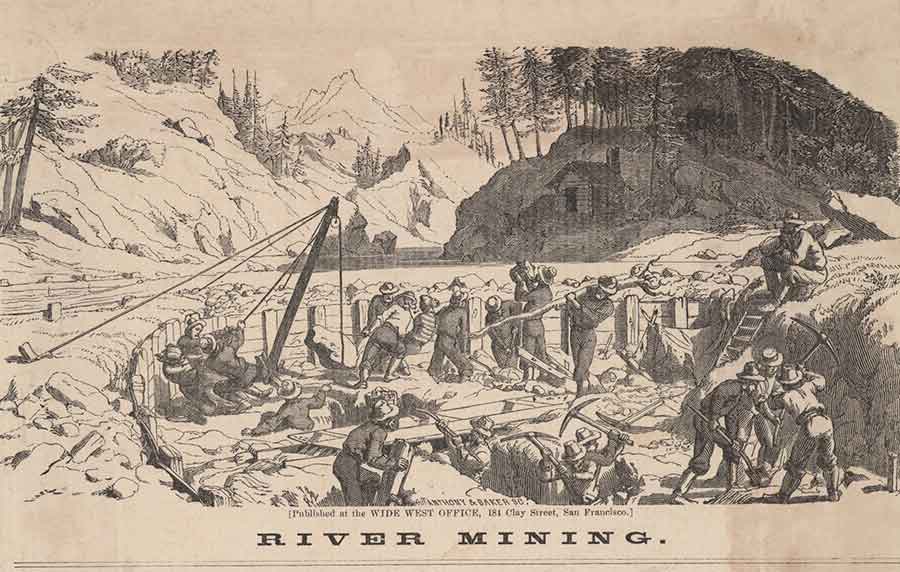

Driven by their lust for gold, many miners refused to let any natural obstacle stand in their way. Some ambitious fortune hunters even organized operations to redirect entire rivers. Erecting dams that would turn the rivers into new channels, laborers would then excavate the exposed riverbeds in search of golden deposits. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Even today, however, the careful observer who travels the mining regions encounters evidence of past practices. At Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park, for example, sheer rock walls, blasted clean by hydraulic jets in the 19th century, tower over the visitor. And, lurking within wetlands, reservoirs, lakes, and waterways, mercury toxins washed out of old mining districts have been transmitted up the food chain from bacteria to waterfowl, to fish, and eventually to humans. Thus the extraction of gold from California’s landscapes more than a century and a half ago—as depicted in these letter sheet images—links the past to our present through the living.

Peter Blodgett is the H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western American History at The Huntington.