The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Wisdom of Premodern Medicine

Posted on Wed., Oct. 21, 2020 by

A physician attends to a bedridden patient and observes a flask of what is likely urine. Urinalysis was among the most common diagnostic tools of medieval medicine. Detail from Es spricht der Meÿster Almanasor, Augsburg, 1483. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

It was an extraordinary and somewhat serendipitous occurrence that led to The Huntington's becoming one of the best institutions in the United States to study European medicine from the latter half of the 15th century. In brief, Henry E. Huntington's purchases of so-called incunabula—books, broadsides, or pamphlets printed in Europe following Johannes Gutenberg's revolution in printing but before 1501—were so massive and extensive that he built one of the largest collections of medical incunabula in North America, evidently by accident.

Other U.S. institutions holding large numbers of incunabula medica today include Harvard University’s Countway Library and the National Library of Medicine, whose collections arose because of a special interest in the history of medicine. Huntington did not apparently have a special interest in the history of medicine and was interested in these items instead for their rarity, beauty, and significance to the history of printing.

Early staff members at The Huntington recognized the importance of this collection; it was librarian Herman Ralph Mead who in 1931 published "Incunabula Medica in the Huntington Library," a useful text enumerating the material. Mead counts 532 medical incunables, and in the approximately 90 years since this list was published, the Library has added several dozen additional items, all of which are now in The Huntington’s online catalog. The Huntington is also in the midst of a digitization project, funded by Board of Governors member Dr. J. Mario Molina, that will bring electronic facsimiles of many of these pre-1501 medical items to a worldwide online audience through the Huntington Digital Library. (You can browse through materials from the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences digital collection that have already been made available, including several incunabula.)

![The Huntington Library holds several incunabular editions of the Fasciculus Medicinae (Little Bundle of Medicine), including the first edition printed at Venice in 1491. This later edition followed an earlier depiction of a university dissection scene but employed block color printing. The mismatched colors of the Sector’s legs remain mysterious. Mundinus, Anatomia (Venetiis: Joannem and Gregorium de Gregoriis, fratres, Feb. 17, 1500 [1501]). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/verso/featured/premodern-medicine_2.jpg)

The Huntington Library holds several incunabular editions of the Fasciculus Medicinae (Little Bundle of Medicine) including the first edition printed in Venice in 1491. The collection of texts included part of Mondino de Liuzzi’s Anatomia and this 1494 edition copies an earlier illustration of a university dissection scene but employed block color printing. The mismatched colors of the Sector’s legs remain mysterious. Ketham, Fasiculo de medicina, and Mundinus, Anatomia, Venice, 1493/1494. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Taken together, The Huntington’s history of medicine holdings provide a unique glimpse into a period when medicine and knowledge of nature grew apace even in the midst of tenacious traditions rooted in the ancient world.

In the second half of the 15th century, when incunables were being published, the medieval world was beginning to shift into what scholars consider the early stages of modernity, driven in part by the proliferation of a variety of printed texts. So, what do these texts—and especially those from The Huntington’s collections—reveal about the healing arts in this transformational time?

First, while important changes were indeed taking place, it would be erroneous to write off all that happened before as the “Dark Ages,” as has often unfortunately happened. The medicine bequeathed to 15th-century Europe was a complex mélange that drew most importantly from ancient sources such as the Roman physician Claudius Galen (129 CE–ca. 200/ ca. 216), the corpus of Greek texts attributed to Hippocrates (ca. 460–ca. 370 BCE), and pharmaceutical texts on so-called materia medica (medical material). Ancient medical knowledge was then preserved but also transformed in the medieval Islamicate world—the greater Mediterranean and western Asian regions influenced by Islamic civilization—by physicians such as al-Rāzī (or Rhazes; 854–925 CE), Al-Zahrawi (or Albucasis; 936–1013 CE), and Ibn Sina (or Avicenna; ca. 980–1037 CE). Indeed, Ibn Sina’s five-volume Canon of Medicine was authoritative in both Islamic and European medicine for more than half a millennium and included advances in pharmacology and pathology, with particularly good descriptions of specific diseases.

![The so-called “wound man” first appeared as early as the 14th century in manuscript form and was first printed in the Fasciculus Medicinae. The illustration shown here is from a remarkably rare vernacular Spanish translation of the Fasciculus from The Huntington’s collections that apparently only survives in six libraries throughout the world. Joannes de Ketham (active 15th century), Epilogo en medicina y cirurgia co[n]venie[n]te ala salud, 1495. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/verso/featured/premodern-medicine_3.jpg)

The so-called “wound man” first appeared as early as the 14th century in manuscript form and was first printed in the Fasciculus Medicinae. The illustration shown here is from a remarkably rare vernacular Spanish translation of the Fasciculus from The Huntington’s collections that apparently only survives in six libraries throughout the world. Joannes de Ketham (active 15th century), Epilogo en medicina y cirurgia, Burgos, 1495. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

It was then in the new universities of medieval Europe where this medical tradition was institutionalized and came to shape a formal body of theoretical and practical knowledge. An iconic woodcut print from one of the most popular medical texts of this era, the Fasciculus Medicinae (Little Bundle of Medicine), illustrates well how tradition and discovery coincided in this learned setting. The illustration (see the second image above) shows the dissection of a human cadaver and accompanies a chapter on anatomy written by the Bologna physician and professor Mondino de Liuzzi (ca. 1270–1326), who gained considerable renown for writing the first book in Europe since classical antiquity devoted entirely to human anatomy that was based on actual human dissections. In the Fasciculus’s depiction of a university dissection scene, the physician “Lector” is seated on high in his academic robes, reading from a text that largely preserved the ancient Galenic understanding of the body. On the far right, the “Ostensor” points out features of interest, while in the center, the “Sector,” a barber surgeon of lower social rank, is the only one carrying out the messy business of dissecting the body.

This mode of anatomical demonstration showed a renewed interest in an empirical understanding of the body but was meant largely to display the authority of ancient authors such as Galen, who had notoriously had been unable to dissect human cadavers. Most of Galen’s anatomical observations were made through the dissection of animals and so led to numerous errors and inaccuracies.

The Huntington’s copy of this rare 1499 edition of the Gart der Gesundheit (Garden of Health) has contemporary coloring and extensive annotations. There are only nine other copies in holding institutions throughout the world, and two of those “copies” are single leaves. The volume’s chapter on nightshade (pictured) mentions that it can have numbing or analgesic effects. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Even so, while the mode of performing human anatomy changed only little, the manner of representation and dissemination made possible by the technology of printing was revolutionary. Taking a cue from Renaissance humanism—the Italian revival, begun in the14th century, in the study of classical Roman and Greek culture—with its increased attention to the human form, the Fasciculus contained the first printed illustrations of human anatomy, and the folio-sized schematic diagrams that were included in the numerous editions and translations of the text influenced generations of anatomists as well as artists.

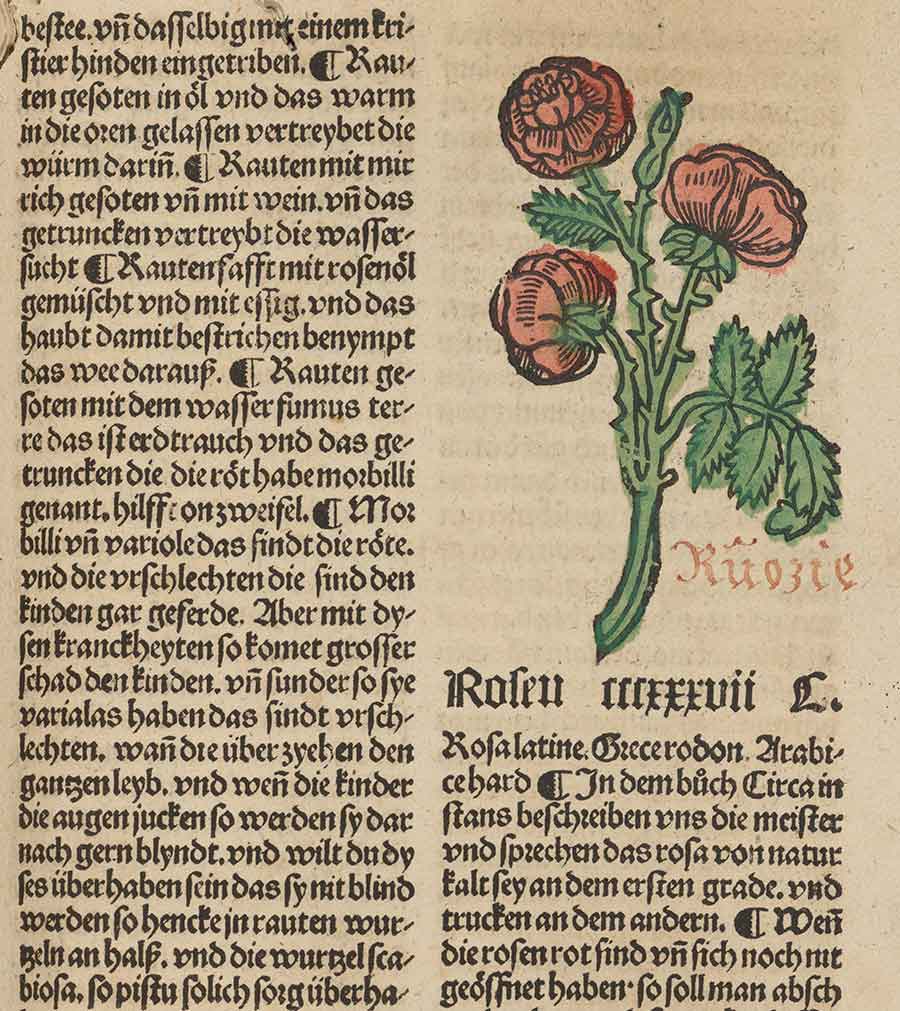

Just as with anatomy, so too with medical botany: A continued emphasis on tradition was influenced by a growing interest in observation, experiment, and new modes of representation. One of the most popular and influential botanical texts from the era was the Gart der Gesundheit (Garden of Health), first published in 1485, which showed, for the first time in print, morphologically accurate depictions of plants in its hundreds of woodcuts. The illustrations were joined by extensive descriptions of the medicinal properties of each plant and were based almost entirely on ancient and medieval authorities.

The Gart der Gesundheit’s description of roses notes cold and dry properties. Among the many references to medical authorities is one in which Ibn Sina links the consumption of rose to a strengthened heart and a cheerful temperament. Cordial liqueurs often included rose, and the word itself has roots in the Latin cordialis, signifying “belonging to the heart.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The chapter on nightshade, for instance, first appeals to Ibn Sina, who noted that the plant was cold and dry, and we then learn from a host of other authors how this cold and dry plant can be used to counteract diseases that are by nature hot and moist, and that it can have numbing or analgesic effects.

The prevailing medical theory of the period was humoralism, a schema in which four bodily “humors”—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—permeate the body and govern health and disease. Each humor has a given temperament on a spectrum from hot to cold, on the one hand, and from wet to dry on the other, and was influenced not just by medicines but also diet and activity.

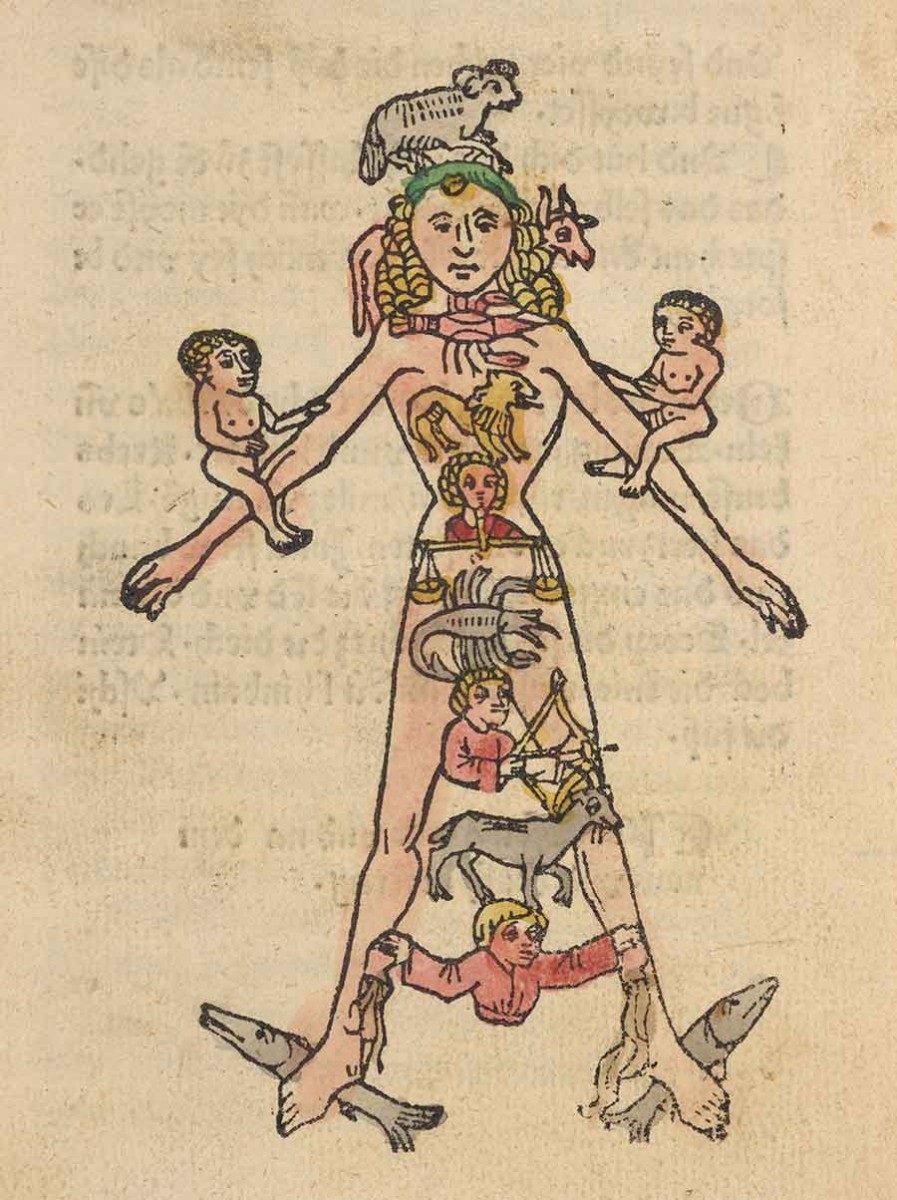

Another central tenet of the medicine of the era was that the balance of the humors fell under the power of astrological forces. This idea is illustrated in the image known as the “Zodiac Man,” which shows a human body in which specific parts of the body are correlated with signs of the zodiac, a band in the sky that is divided into 12 constellations or signs. (For example, the feet were correlated with the zodiac sign Pisces, represented by two fish.) These associations helped physicians choose times to administer medication, perform surgery, or balance the humors by letting, or withdrawing, blood, the principal rule being to avoid interfering with a specific body part while the moon was passing through its corresponding sign.

The “Zodiac Man” shows a human body in which specific parts of the body are correlated with particular zodiacal signs. For example, the feet are correlated here with the zodiacal sign Pisces, represented by two fish. The “Zodiac Man” is one of the most common illustrations in medieval medical texts. This particular version of the image, however, is very rare. The German “Kalender” in which it appears is known only in three libraries throughout the world, with both other copies being in Germany. Detail from Es spricht der Meÿster Almanasor, 1483, Augsburg. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Late medieval medicine, as recorded in medical incunabula, has borne its share of criticism, and much of it is valid. Bloodletting was likely not only ineffective but actively harmful to most patients, and the belief that human bodies are composed of humors governed by the stars has not been supported by modern medicine. Even so, the systems developed had an elegant coherence and considerable explanatory power, and the nascent empiricism evident in the texts was certainly influential in the emergence of the experimental science of the early-modern era.

Likewise, the specters of bloodletting and humoralism should not diminish the many effective diagnoses and treatments that were integral parts of medical practice. Surgeons cauterized wounds, extracted teeth, and amputated diseased limbs; midwives delivered children and cared for women through pregnancy and beyond; and physicians prescribed many remedies now known to be therapeutic.

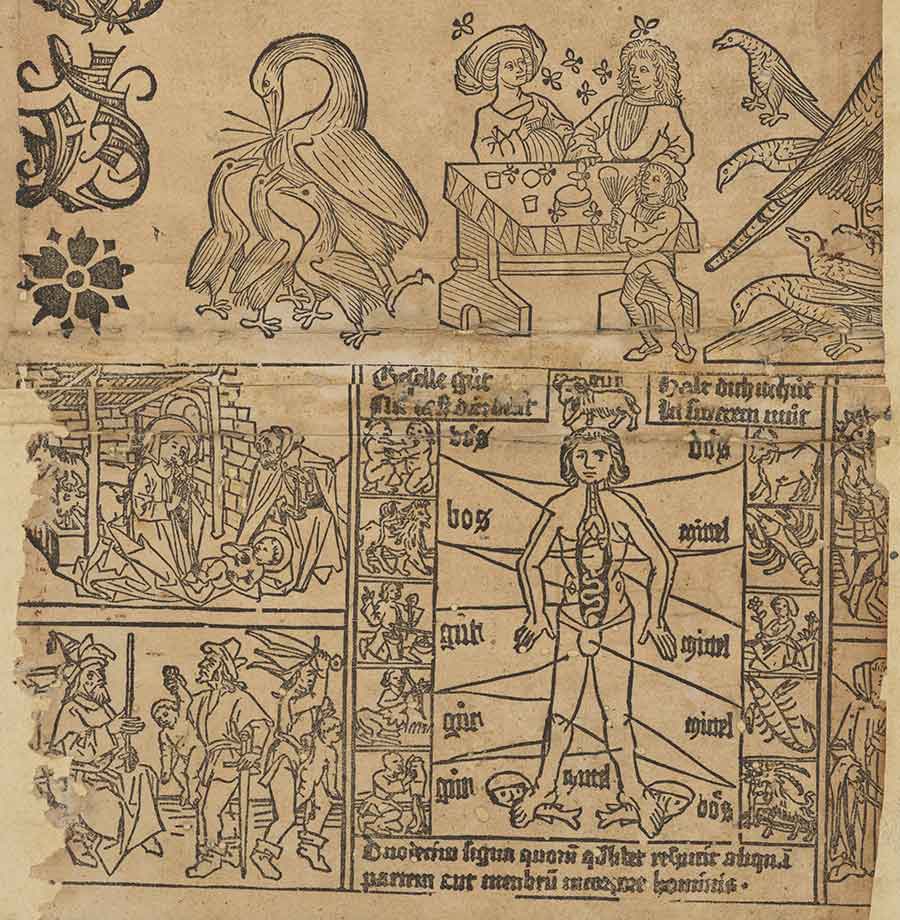

This Aderlasskalander (bleeding calendar) is a German astrological almanac that has instructions about favorable times in which to let, or withdraw, blood and purge the body. It is not entirely clear when this item was printed, and one of the reasons this document remains mysterious is that it is unique: The Huntington’s copy is the only one known to exist. It owes its survival to its use as “waste” pasted into the binding of a book to give it structure, and it is unclear when or from whence the item was removed. Detail from Aderlasskalander mit biblischen und zoologischen figuren. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As I write from home during the worst infectious pandemic to strike in several generations, there are reasons why, even with the benefit of modern medical technologies, it is difficult to feel much superior to this earlier era. Many nations—including New Zealand, South Korea, and Taiwan—have managed to quell outbreaks of the novel coronavirus using technology and medical protocols that were familiar in the medieval world.

Indeed, the oft-printed pamphlet entitled A litil boke the whiche traytied many gode thinges for the pestilence, first published in 1485, outlined means to prevent the spread of infectious plague. The Huntington’s edition of around 1511 instructed doctors to stand far from sick patients, “holdynge their face towarde the dore or wyndowe.” It admonished readers to “wasshe your handes ofte tymes in the day with water and veneger,” explaining that “in the tyme of pestylence it is better to abyde within the house, for it is not holsome to go in to cyte or towne.”

The reasons for the continued spread and devastation of COVID-19 are, of course, complex and compound. And yet I wonder what wisdom we have forgotten and what we still might learn from the medical texts of the incunabula era.

You can learn more about The Huntington’s collections in the history of medicine through this research guide. For a companion guide to the recorded virtual presentation “Huntington Incunabula in the Digital Era," visit here.

Joel A. Klein is the Molina Curator of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington.