The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Ecologies of Paper

Posted on Wed., Nov. 4, 2020 by

Joseph Basil Girard, Landscape with Trees, Oct. 15, 1890, watercolor on paper, 5 x 3 1/2 in. (12.7 x 8.9 cm.), purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The word “ecology” is a relational term. It speaks to the interdependency of organisms, objects, and systems with their environments. “Ecology” can also be used as a term of advocacy, one that promotes the conservation of natural resources. Constructing a history of the ecologies of early modern paper might involve nominating one particular material support—paper—as the locus of human claims upon landscapes. Or, such a project might be conducted by looking to paper as a substitute for other supplies that have run scarce (paper money over silver and gold coin). Paper was recycled rather than discarded; it promoted a model of transformation rather than an accumulation of waste. These ideas represent some of the possible approaches that will take shape during “Ecologies of Paper in the Early Modern World,” an online conference I am co-convening with Caroline Fowler on November 5 and 6, 2020.

The ancient Greek word οἶκος (dwelling) is embedded in the German Oecologi (coined by the zoologist Ernst Haeckel) and its English derivative, “ecology.” This etymology secures the place of architecture as a primary means of mediation between organism and environment. One way to situate “Ecologies of Paper,” as a method, then, is to think of paper as playing the role of architecture—paper as host to ideas that establish the relationship of humans to land.

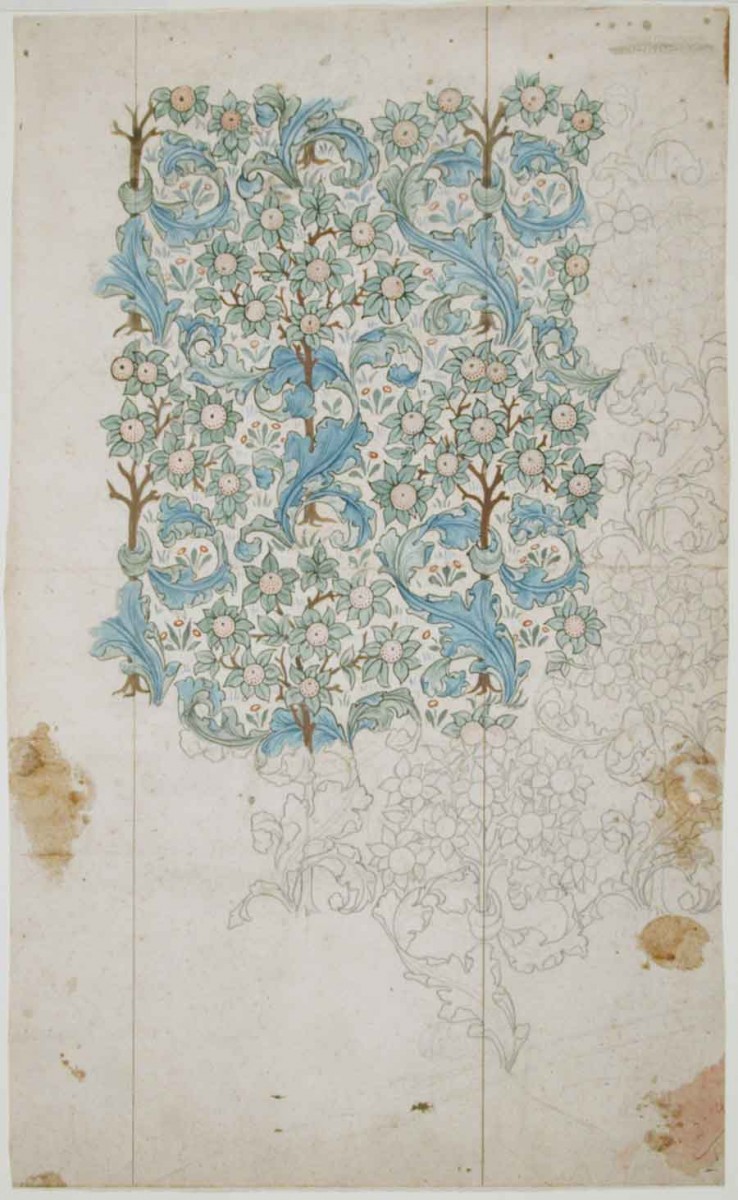

John Henry Dearle, Orchard , ca. 1900, watercolor and graphite on paper, 13 1/4 x 8 1/4 in. (33.7 x 21 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

To do this is to focus on documents that distribute resources or restrict their use, that attempt to establish the domination of settlers over Indigenous populations and their habitats; it is to figure the relationship of currency to capitalism and nature to nationhood. Such an approach names the authority that paper holds—its ability to document, charter, legalize, and establish networks of credit and debt—its constitutive role in the structural reshaping of society. To test such claims requires challenging the durability of paper against the unrecorded operations of oral traditions, migrations, destructions, and reliances on customary laws. While paper has the potential to protect such ephemeralities, it can also erase them.

Paper—in the artist’s studio, on the writer’s desk, under the notary’s seal, and in the printer’s shop—was never merely a support; it served as the site of conversion. Paper was where ideas were externalized with a particular immediacy to become visible expressions and communications, but it also embodied the paradox that worthless rags run through the watermill could signify capital. Paper was, on the one hand, something to keep. Over the course of the 15th and 16th centuries, hand-marked sheets, such as sketches and correspondences, gained increasing material value and a newly awarded status as collected items. Both drawings and letters made their way into the collections of connoisseurs. But paper also traveled far. It was brought by Europeans to the New World along with domesticated animals, weeds, disease, a spreadable religion, and an infrastructure for subjugation.

E. A. Burbank, Group of Trees, graphite on paper, 1946, 10 1/16 x 10 1/8 in. (25.6 x 25.7 cm.), Gift of Mrs. Adelaide Bray. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Where do these two approaches—the one that considers paper as a binding agent between organism and environment, the other that understands paper as involved in a process of remaking—meet? Our conference brings together 12 scholars representing three continents, each of whom has a different answer to propose. Geographically distanced by the pandemic, our speakers will be brought together by—and will even comment upon—our era’s virtual alternative to the material properties of paper and the social actions available in shared space.

Funding for this conference has been provided by The Philip V. and Sara Lee Swan Endowment.

Shira Brisman is assistant professor of early modern art at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of Albrecht Dürer and the Epistolary Mode of Address (University of Chicago Press, 2016) and is currently preparing a second book, The Goldsmith’s Claim: German Renaissance Art as Material and Intellectual Property. For the 2020–21 academic year, she is a faculty fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wolf Humanities Center, which convenes around the research topic “Choice.”