The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Fascination with Flax

Posted on Wed., Dec. 9, 2020 by

Kelly Fernandez, head gardener of the Herb Garden and the Shakespeare Garden, harvests bundles of flax from The Huntington’s Herb Garden. Photo courtesy of Kelly Fernandez.

When Kelly Fernandez, head of the Herb and Shakespeare gardens, revived The Huntington’s Fiber Arts Day program in 2013 and saw expert craftspeople dyeing, spinning, and weaving fibers into incredible textiles, she couldn’t help but be intrigued.

In the years since, she's acquired her own spinning wheel, started handcrafting textiles, and even traveled to Oaxaca to learn from textile artisans from around the region. "I got the bug. I couldn't help myself," Fernandez said. "I started out being the organizer, and now I'm also a participant."

This year, Fernandez took her love of textiles one step further. Deeply intrigued with all aspects of the process of creating textiles, Fernandez decided earlier this year to grow, process, and spin her own flax—the fiber used to make linen.

Left: Flax in bloom earlier this year in The Huntington’s Herb Garden. Right: Flax bundles harvested and tied for drying. Photos by Kelly Fernandez.

The project started in January when Fernandez planted flax seeds in The Huntington’s Herb Garden and monitored them as the stalks grew through the spring. By April, Fernandez knew it was time to harvest the stalks because the stems had started to yellow. With apologies to Snow White (whose finger was pricked by a flax sliver in the original version of the fable), flax harvesting is more of a Goldilocks process: Pick it too early, and the flax will be too weak and fine. Pick it too late, and the flax will be coarse and rough. “You really have to watch it,” Fernandez said.

When the stalks were deemed ready, Fernandez pulled the plants out with roots intact to dry them. “They need to be bone dry. It takes a month,” Fernandez said.

Dried flax being retted in the waterfall in The Huntington’s Jungle Garden. Photo by John Villareal.

Once dried, Fernandez had roughly 40 pounds of flax. But the hard work was just beginning. Flax must undergo a process called “retting” so moisture can help separate the flax fibers from the cellulose core. In the colder climates where flax is normally grown, this can occur outdoors. “You can just lay the flax out in a field and let the dew and moisture ret for you,” Fernandez said.

Here, in warm and dry Southern California, Fernandez had to be more resourceful. So, she used the waterfall in The Huntington’s Jungle Garden, submerging the flax under water for seven days. “That was a fun thing to do,” Fernandez said. “Of course, I asked permission.” Retting is also a bit of an art, she said. If you don’t allow enough time, the fibers will be hard to separate. Wait too long, and the fibers may become weak.

It was useful to be able to use a stream, Fernandez said, because as the stalk dissolves and separates, with the help of a lot of bacteria, “it really is this gross, smelly stuff,” she said. “I felt very lucky to have a waterfall on hand.”

Alicia Baugh, a plant propagator at The Huntington, helps break flax by hand. Photo by Kelly Fernandez.

Once that was done, it was time for breaking and scutching, processes that separate the plant’s hard cellulose core into pieces to free the flax fibers. Most professional flax growers have large tools for this step, but such tools are not easily found. “You can’t find them on Amazon,” Fernandez said. “You either need to make them or get them made.” Instead, Fernandez and Huntington staffers Alicia Baugh and Jenny Long broke the flax by hand.

“Unfortunately, I don’t have any of these tools,” said Fernandez. “What I have is people who are willing to help.”

“It’s very easy and fun,” Fernandez added. “This is something you can do with kids.”

The final step was “hackling”—running the flax through a series of combs. (The golden color of the fibers is the reason blond hair is often described as flaxen.) Fernandez, who hopes to obtain better and larger flax tools in the future, made do with a mini hand hackle to collect enough fibers to start spinning.

Hackling flax with a comb helps make the plant fibers smooth, parallel, and of equal length. Photo by Kelly Fernandez.

The inspiration for her project, Fernandez said, came not only from the Herb Garden and artisans who demonstrate their textile skills during Fiber Arts Day, but also from works she sees inside the galleries and from the art collections of The Huntington. One inspiration was the striking spinning wheel featured in the Fielding Collection. “I would love to try spinning on a wheel like that one day,” Fernandez said.

That 18th-century wheel in the Fielding Collection, it turns out, wasn’t for spinning flax, but was likely for spinning wool, said Dennis Carr, the Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art and an expert on Latin American textiles. The wheel, which was made in Cape Cod, is simpler than those used for flax, which typically contain more elements, like a distaff or spindle for unspun fibers, he said.

The Huntington’s art collections, Carr said, contain numerous images of spinning, which was a popular theme in the late 19th-century Colonial Revival movement, when people took solace in images that represented a simpler past.

Left: Using a spinning wheel, Fernandez spins flax fibers into thread. Photo by Kelly Fernandez. Right: Spinning wheel, American, early 18th century, wood and paint. Gift of Jonathan and Karin Fielding. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

That simplicity certainly resonates with Fernandez. “Spinning is calming and meditative,” she said. “Once you’re in the flow, you can go for hours.”

And it did take hours for Fernandez to spin her homegrown flax into yarn. The 40 pounds of flax she had harvested yielded a small seven-ounce ball of fine yarn. (However, more thread could be produced from the coarser fiber, called tow, which can be used for twine or rope.) For Fernandez, it was an important lesson. “That gives you a bit of perspective, to see how much you have to go through to end up with enough material to make a small scarf,” she said. The experience has given her respect for artisans of today and of the past. “It’s fascinating to think about how much processing and skill is involved in creating any textile,” she said.

In researching the fiber, Fernandez was thrilled to learn that The Huntington has its own flax expert in residence. Steve Hindle, the W.M. Keck Foundation Director of Research, studies the social and economic history of early modern England. In his work, Hindle has used flax as a barometer of domestic production and analyzed probate materials to discover the value of such items as spinning wheels, as they were passed from mother to daughter. “It’s an interesting opportunity to reconstruct the history of material production,” he said.

The final product after months of hard work: many valuable lessons and a seven-ounce ball of thread. Photo by Kelly Fernandez.

This historical lens reveals that although the weaving of flax and hemp to produce linen played a crucial role in village economies from 1600 to 1650, their importance declined rapidly after the emergence of lighter fabrics such as silk and cotton. Hindle’s analysis of the Warwickshire village of Chilvers Coton showed that 12 households shared as many as 22 wheels for spinning linen before 1650. A few decades later, there were just five wheels across two households.

“The shift in preference for textiles was an index of the growing consumerism of the late 17th and early 18th centuries,” Hindle said. “Consumers wanted not only fabrics that were lighter, but those which could be dyed and patterned to keep up with the latest fashions,” he said.

Fernandez’s project met with the approval of her supervisor, Jim Folsom, the Marge and Sherm Telleen/Marion and Earle Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens, who has long appreciated flax, or Linum usitatissimum, for its many uses. Folsom also appreciates the many ways the plant is woven through human history and has intersected with some of the most treasured items in The Huntington’s collections. Linseed oil, a product of the flax plant, was used by Johann Gutenberg in the 15th century to create the long-lasting ink that he used to print his bibles; Joshua Reynolds used linseed oil in the 18th century to create the varnish that protected his famous portrait of actress Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse. “Flax has been around for a long time,” Folsom said. “It’s the oldest known seed crop in archaeological middens from 30,000 years ago.”

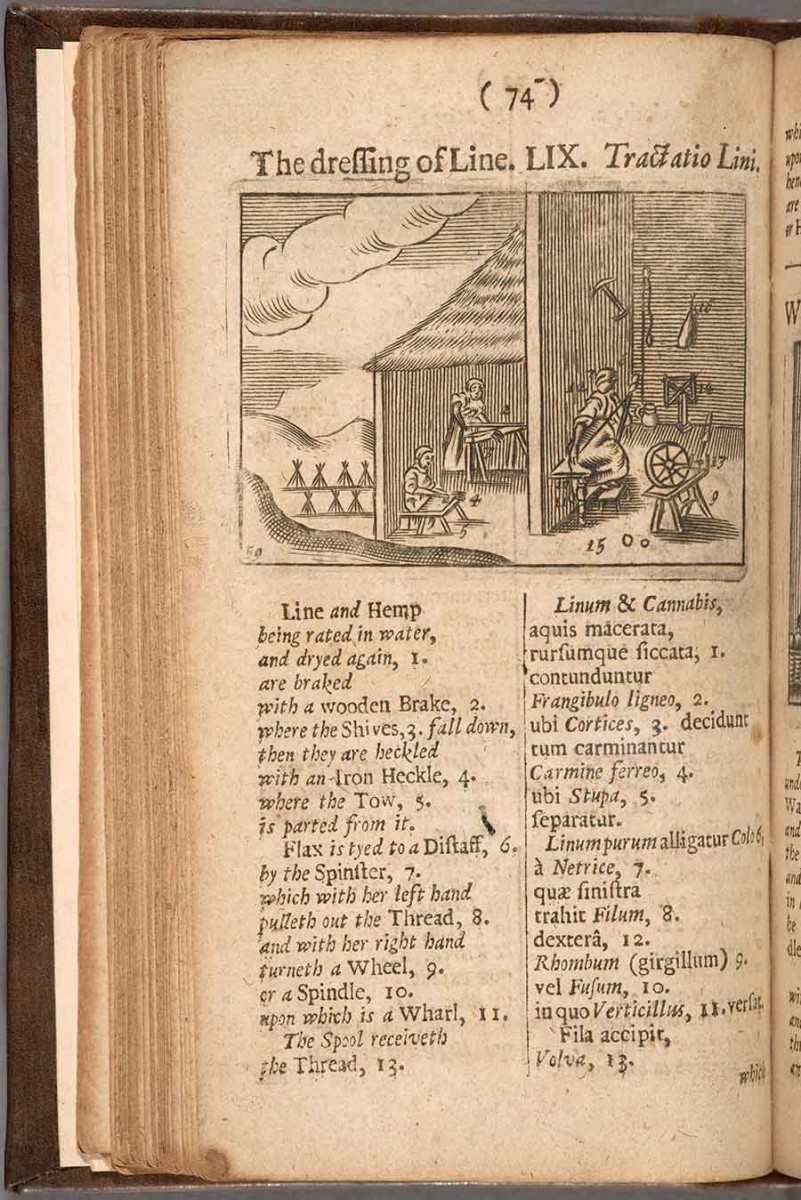

A page from a 1705 edition of the children’s textbook Orbis Sensualium Pictus (Visible World in Pictures), by Johann Amos Comenius, 1592–1670. The illustrations depict the processing of flax. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

While once grown in nearly every U.S. state, flax has experienced a dramatic drop in production in recent years. It is now grown primarily in North Dakota and Minnesota, not to produce linen, but to produce flax oil, which has become popular because of its potential healthful properties.

Next for Fernandez? She has started weaving her linen thread to make cloth. Hoping to hone her skills further, she is also preparing to plant a new crop of flax so she can work through the process once again. “This project tells a fascinating story of our connections to plants through history,” she said.

Usha Lee McFarling is senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.