The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Burning of the Old South Church

Posted on Wed., Jan. 27, 2021 by

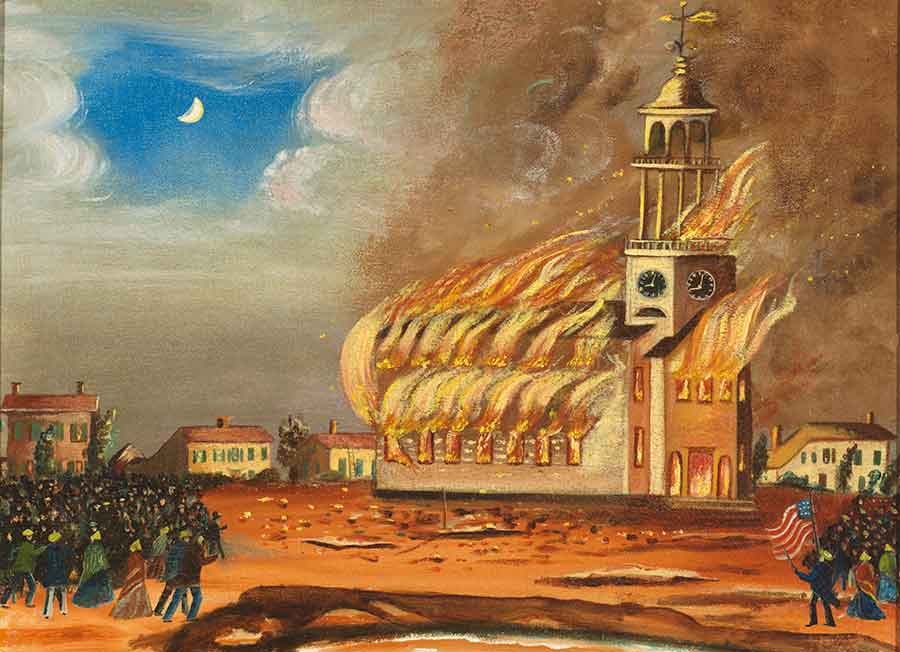

John Hilling, Before the Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 27 7/8 x 2 1/8 in. (55.2 x 70.8 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Rising class divisions. Economic uncertainty. Anti-immigrant fervor.

It was July 6, 1854. Riled up by a fiery speech by an itinerant “haranguer,” according to period accounts, an angry mob descended upon the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, breaking windows, ransacking the interior, and setting it ablaze. Many in the mob were members of a growing political movement in the United States, referred to as the Know-Nothing or American Party, which supported a platform of anti-immigration, suppression of voting rights, and nativist policies. When asked what they were up to, adherents were told to reply, "I know nothing."

Virulent anti-immigrant, in particular anti-Catholic, sentiment spread like wildfire in many parts of New England in the mid-19th century, fueled by rising immigration and a stagnant economy, and following similar—often also violent—anti-Catholic riots elsewhere in the United States. The Old South Church had long served as a site of worship for the town’s mostly Protestant residents; however, attendance at the church had dropped off in recent years and the new proprietors rented the building to a congregation of Catholic parishioners, some lately arrived in Maine fleeing the potato famine in Ireland or coming to build the Portland and Kennebec Railroad.

Before the match is struck, a man has climbed to the belfry to unfurl an American flag. The clock on the church’s tower tells the time: 7:40 in the evening. John Hilling, detail of Before the Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 27 7/8 x 2 1/8 in. (55.2 x 70.8 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Bath sign and ornamental painter John Hilling, whose house stood a short distance from the church, took a special interest in the dramatic event, painting at least six known versions of The Burning of the Old South Church. One set of paintings is on loan to The Huntington from Los Angeles- and Maine-based collectors Jonathan and Karin Fielding and is currently on view in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. In the pendant pair, one painting shows the rising action, just before the match is struck, with looters surrounding the church, carrying makeshift battering rams, and hurling broken pieces of the shutters from the windows. A man has climbed to the belfry to unfurl an American flag. The clock on the church’s tower tells the time: 7:40 in the evening.

The next painting presents the climax of the tragedy as flames erupt from the windows, shortly before the church was reduced to ashes. “[T]he shouting and yelling of the multitude, above fifteen hundred in number, could be distinctly heard at a distance of a mile,” the New York Daily Times reported on July 11, 1854. “At this time the building seemed to be on fire in thirty places simultaneously. In less than an hour the old bell which had so often tolled its knell from the tower, came to the ground, and the whole structure had disappeared.”

John Hilling, The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 27 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (54.6 x 69.5 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington’s collection includes many works and archival sources from this chapter in American history. The Library’s holdings contain period books written by Know-Nothing leaders, including Thomas R. Whitney’s famous 1856 tract, A Defence of the American Policy, as opposed to the Encroachments of Foreign Influence, and especially to the Interference of the Papacy in the Political Interests and Affairs of the United States. The highest-profile item is perhaps a letter from Abraham Lincoln written to Owen Lovejoy on August 11, 1855, in which he refuses an alliance with the Know-Nothings, who had just scored important electoral wins: “Not even you are more anxious to prevent the extension of slavery than I … I have no objection to ‘fuse’ with any body provided I can ‘fuse’ on ground that I think is right.”

Ultimately, the electoral power of the Know-Nothing Party was short-lived as national political concerns shifted toward issues of slavery and states’ rights and away from immigration; however, their platform tenets lived on in later political movements and ultimately played a role in shaping the two-party system we have today.

![“[T]he shouting and yelling of the multitude, above fifteen hundred in number, could be distinctly heard at a distance of a mile,” the New York Daily Times reported on July 11, 1854. Detail from The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine by John Hilling, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 27 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (54.6 x 69.5 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/verso/featured/burningchurch_4.jpg)

“[T]he shouting and yelling of the multitude, above fifteen hundred in number, could be distinctly heard at a distance of a mile,” the New York Daily Times reported on July 11, 1854. John Hilling, detail of The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, ca. 1854, oil on canvas, 21 1/2 x 27 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (54.6 x 69.5 x 5.4 cm.). Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Hilling’s paintings stand as a record of a rather unseemly moment in New England history, when residents of a town, energized by charismatic leaders, turned against their neighbors based on issues of religion, class, and birthplace. In our incendiary political moment today, when roughly one in seven people living in the United States are immigrants—among the highest percentages since the 19th century—these ripped-from-the-headlines paintings are again especially resonant and relevant.

You can find information on thousands of paintings, drawings, prints, sculpture, and other works of art online in The Huntington's art collections catalog.

Dennis Carr is the Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art at The Huntington.