The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

“The Paths of Honour, Truth and Virtue”

Posted on Wed., Feb. 10, 2021 by

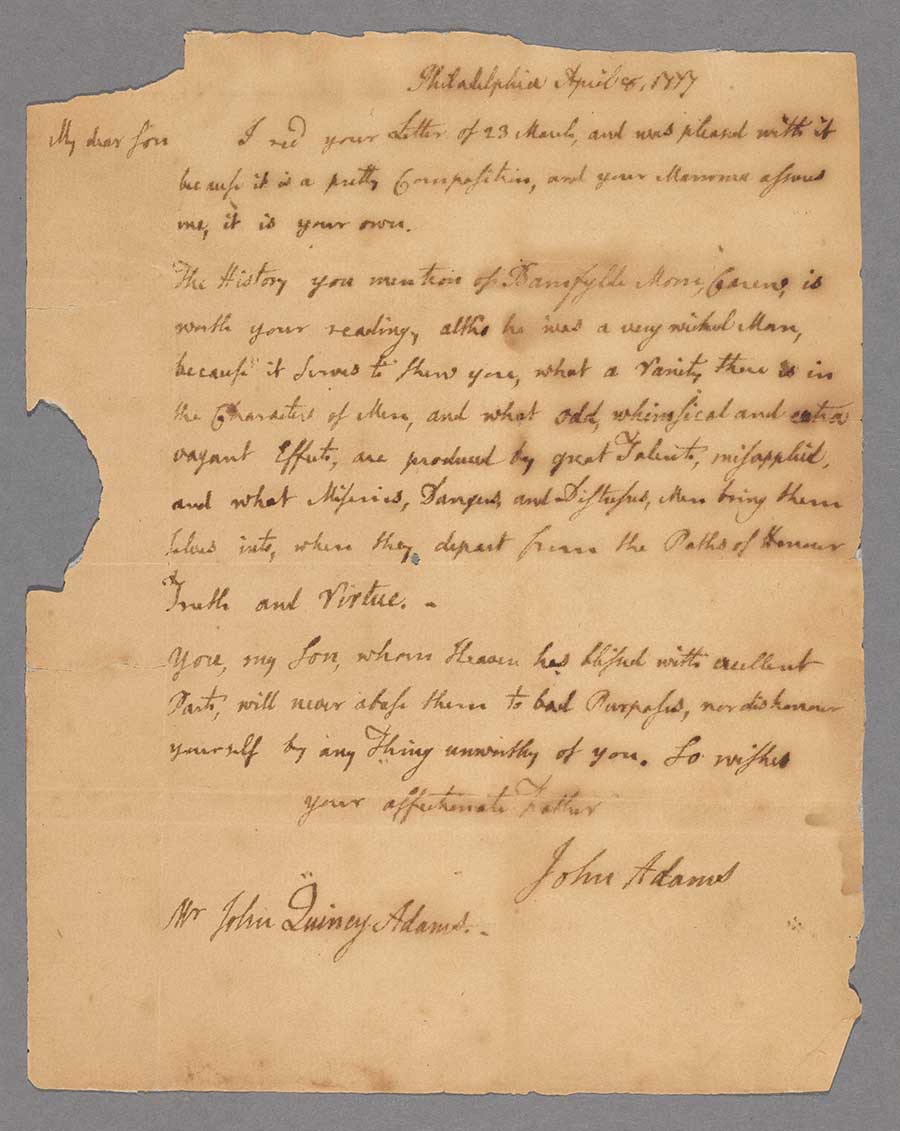

Letter from John Adams (1735–1826) to his son John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), April 8, 1777. John Adams served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. John Quincy Adams served as the sixth president of the United States from 1825 to 1829. L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

On April 8, 1777, John Adams, the future second president of the United States, wrote a letter to “Mr. John Quincy Adams,” his eldest son and the future sixth president. The letter, a reply to his son's missive of March 23, 1777 (now held by the Massachusetts Historical Society), came to The Huntington in 2019 as part of the collection of L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro, founders of the Shapiro Center for American History and Culture at The Huntington, which includes some 340 rare items focused primarily on American presidential administrations from the 18th to the early 20th centuries.

Ever since June 1774, when the Massachusetts legislature had appointed him a delegate to the Continental Congress, John Adams had spent most of his time in Philadelphia (and, for two winter months of 1777, in Baltimore, where Congress was evacuated to avoid British forces). His wife, Abigail Adams, and their children stayed home on the family farm in Braintree, Massachusetts: 11-year-old Abigail (Nabby), nine-year-old John Quincy (Johnny), and two younger boys—Charles, four, and Thomas, two.

John and Abigail Adams would fit the modern definition of "helicopter parents," especially when it came to Johnny, the star of the family. The boy was educated at home, with his studies, reading, and leisure time guided by his mother and closely supervised by his absent father, as seen in frequent letters from John to Abigail. Beginning in July 1776, Adams also wrote directly to Johnny.

John Adams (1735–1826) served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Lithograph by Kurz & Allison (Chicago), ca. 1886. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Just like all parents, the Adamses wanted their son to succeed in life. But, even more urgently, they wished to see him grow into a true “American Gentleman” who would take his place in what Adams’s friend Thomas Jefferson called an “aristocracy of virtue and talent.” On June 29, 1777, in a letter to Abigail, Adams sketched out a curriculum designed to make Johnny into a “wise and great man” who would “know that the sentiments of his heart are more important than the furniture of his head” and “possess the great virtues of temperance, justice, magnanimity, honor, and generosity." The best way to achieve this worthy goal was, according to Adams, an education that would elevate the boy’s mind, fix his attention on “great and glorious objects,” distract him from “little things,” and weed out “every meanness.”

On April 8, 1777, in The Huntington's letter, Adams congratulated Johnny on “a pretty Composition" of a letter which, he added, “your Mamma assures me is your own.” Much of Johnny’s letter was devoted to his thoughts on a book he had been reading that seemed to undermine every value that Johnny’s parents labored to instill.

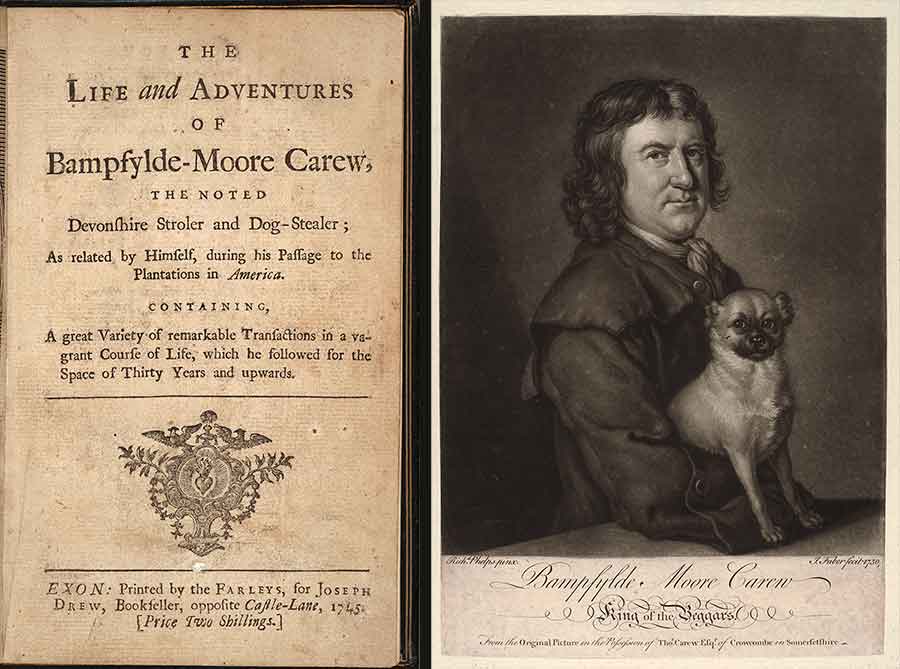

The Life and Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew, first published in 1745 and printed in numerous bestselling editions, was an autobiography of a swindler. In many ways, Carew was a progenitor of Frank Abagnale, Jr., the subject of Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film Catch Me If You Can. A wayward son of a respectable Devonshire minister, Carew (1693–ca. 1770) used his considerable talents—most notably the power of persuasion, which apparently extended to dogs, as Carew could “entice any dog whatever to follow him"—and a gift to take on a “great Number of Characters and Shapes” to convince countless ladies and gentlemen on both sides of the Atlantic to part with their money.

John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) served as the sixth president of the United States from 1825 to 1829. Lithograph by W. Ball, after the portrait by Gilbert Stuart (New York, 1834–40). Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

It is easy to see why a nine-year-old child would be attracted to the book. Like other children of his age, Johnny enjoyed reading for fun, and the story of Bampfylde Moore Carew is great fun, even today.

As some children today claim that video games have educational value, Johnny highlighted the useful passages in the book. It offered “a very pretty Desscription of maryland and philadelphia and new York” and taught an important moral lesson. Despite all the money he managed to get and the adventures he enjoyed, Carew’s life was a waste, “for he addicted himself to so many falsehoods” and became “a disgrace to human nature.”

This was exactly what John Adams wanted to read. Replying to Johnny, he assured his son that, even though Carew was “a very wicked Man,” the book was “Worth your reading.” It showed that, even as there existed a great “Variety of the Characters of Men,” so there were “odd, whimsical and extravagant Effects” that resulted from their actions. More importantly, Carew’s story demonstrated that the possession of high intellect, charm, and good breeding did not make a man good. When men depart from “the Paths of Honour, Truth and Virtue,” John Adams wrote to his son, they bring about “Miseries, Dangers and Distresses.”

Left: Title page of The Life and Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew, 1745. Right: Bampfylde Moore Carew, King of the Beggars, mezzotint by John Farber, Jr., after the portrait by Richard Phelps, 1750. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Concluding his letter, Adams stated: “You, my Son, whom Heaven has blessed with excellent Parts, will never abase them to bad Purposes, nor dishonour Yourself by any Thing unworthy of you.”

Seventy years later, John Quincy Adams—a distinguished diplomat, celebrated lawyer, inveterate enemy of slavery, and the first and only former president to cap his career with 18 years in Congress—collapsed on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives while vigorously protesting what he believed to be an illegal war with Mexico. Before he slipped into a coma, he thanked the officers of the House who carried him to the Speaker’s Room, where he died two days later, on Feb. 23, 1848.

As the funeral train carried his body to Massachusetts, hushed crowds lined the tracks, mourning the death of a truly great man who, in the words of the clergyman and educator Rev. Joshua Bates, had used his carefully cultivated talents to “promote the happiness of others.” His parents would have been proud.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.