The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Connecting with Mary Cassatt’s Pastels

Posted on Wed., March 10, 2021 by

Left: Mary Cassatt, Young Girl in a Large Hat, 1908, pastel on paper, 25 1/4 x 19 1/2 in. Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Mary Cassatt, Françoise Holding a Little Dog, 1908, pastel on paper, 26 7/8 x 22 3/4 in. Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Michelangelo and marble. Andy Warhol and silk screen. Yoko Ono and performance. Some artists have strong associations with specific mediums.

We can add to the list the trailblazing American artist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926). For many, her name evokes dense, brushy oil paintings like The Huntington’s Breakfast in Bed (1897).

But Cassatt was also an avid pastelist. The Huntington has two of her pastels made in 1908, when she was 64 years old: Françoise Holding a Little Dog and Young Girl in a Large Hat. They invite us to appreciate Cassatt’s drawings as much as her paintings, and they illuminate a chapter of her life that is less known than her youthful days in Paris, where she fought for the acceptance of Impressionism. The pastels also reveal connections between Cassatt and two other women: a young girl named Françoise, and one of The Huntington’s founders, Arabella Huntington.

Mary Cassatt, Breakfast in Bed, 1897, oil on canvas, 23 x 29 in. Gift of the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Cassatt has a deserved reputation as a forward thinker. She pursued an art career at a time when it was discouraged for women. For many 19th-century Parisians, her Impressionist style was even more troublesome than her bucking of gender roles. She was also innovative in her use of pastel. Most artists of the era made pastel sketches as preparation for paintings. Cassatt saw them as finished works, including them in her exhibitions.

Not only was Cassatt’s conception of pastel unique, but she was good at it. Looking closely at the girl’s skin in either drawing, especially her face, we notice hundreds of flecks of electric blue. From a distance, they are barely detectable, though their combined effect makes the skin look soft and translucent. In both pictures, the artist has captured certain areas in an expertly sketchy, bold way. Yet like the flecks of blue, the rougher sections cohere to the whole, at the same time nudging us to see the image as Cassatt’s active construction. And could she match colors! Seafoam, gold, and cotton-candy pink. Teal, tea-green, and ochre. And within those blocks of color: more colors!

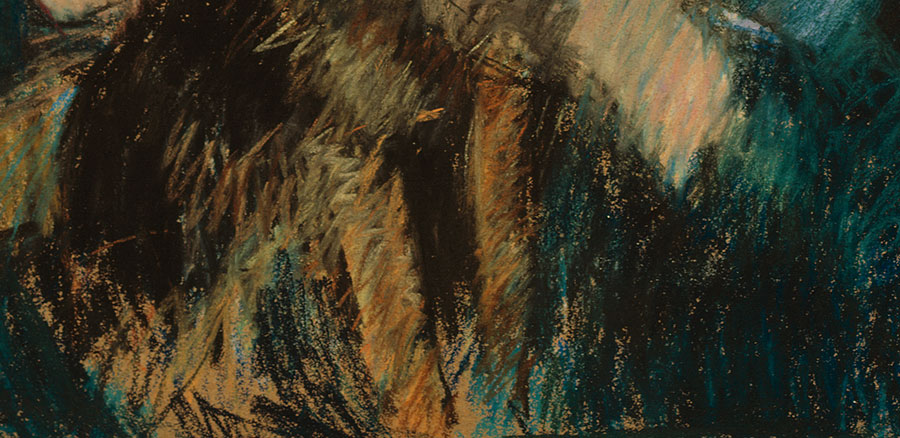

Detail of Young Girl in a Large Hat. Cassatt rendered Françoise’s face with numerous flecks of bright blue. They are hardly noticeable from a distance, helping the skin appear soft and translucent. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Cassatt had made pastels since the 1880s, but her output increased in the decade she completed the Huntington drawings. Around 1900, she began a new venture that kept her crisscrossing the Atlantic: art consulting for deep-pocketed, fellow Americans. Most notably, she guided the purchases of famed collector Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929).

The first decade of the 20th century was a period of emotional strain for Cassatt. She lost several family members and fell out with her fellow artist and longtime friend Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Pastel was less of a commitment when she may have been too busy or unmotivated to paint. Yet it had qualities she liked in painting, particularly bright colors and texture. Though she may not have relished long hours at an easel at this time, Cassatt sustained her creativity through pastel.

Both of the Huntington drawings feature a girl named Francoise, who lived in the same village, 45 miles northwest of Paris, where Cassatt had retired in 1894. The artist captured her in at least 13 paintings and pastels from 1908 to 1909. The girl always wears the same curled hair, and, curiously, a red ribbon.

Detail of Françoise Holding a Little Dog. Cassatt’s drawings of Françoise feature areas of high realism, as well as areas like this one that are almost abstract. Amazingly, the image, as a whole, still coheres. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The frequency with which Cassatt depicted Françoise suggests that they developed a rapport, and even more strongly, that there was something the artist related to in her model. This appreciation has not always been shared by art historians, who have called Françoise “dull.” Personally, I feel she is misunderstood—not “dull,” but serious. In 19th-century France, girls were expected at a very young age to behave like little women. Cassatt, in her heavy emotional state, may have been grateful for this no-nonsense child who was older and more self-contained than the toddlers she typically painted.

Mary Cassatt, Françoise in Green, Sewing, 1908–1909, oil on canvas, 32 in. x 25 3/4 in. Gift of the Ida Belle Young Art Acquisition Fund. Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery Alabama, 2009.6.

Yet how she felt about Françoise’s gravity—outside of its temporary convenience—is a mystery. Herself serious, driven, and opinionated, the artist perhaps glimpsed something familiar and admirable in the girl. Françoise Holding a Little Dog seems to both mock and celebrate their shared trait, contrasting the girl’s sternness with the frenzied Brussels Griffon, hinting at a comic attempt to keep the animal still while maintaining a dignified veneer. But to my eye, Young Girl in a Large Hat has a different tone. Françoise looks less engaged, indeed, slightly forlorn, in a lady’s hat far too large for her. Was Cassatt’s empathy less about a natural personality trait, and more about the shared social burden of female “decorum”? Regardless, despite subdued expressions and poses, Cassatt’s dynamic, confident pastel-work brings her model’s inner life to the paper’s surface.

The Huntington drawings were purchased by the institution’s matriarch, Arabella Huntington (1850–1924), shortly before her death. In addition to this connection, Cassatt and Arabella share other parallels. Both were American women of the same generation and East Coast milieu. Both loved France and the dog breed Brussels Griffon. Arabella’s Griffon, Buster, traveled everywhere she did and is buried at The Huntington. Cassatt’s multiple Griffons are memorialized in many of her artworks and were described by a contemporary as “barking and scampering . . . ill-natured and overfed.”

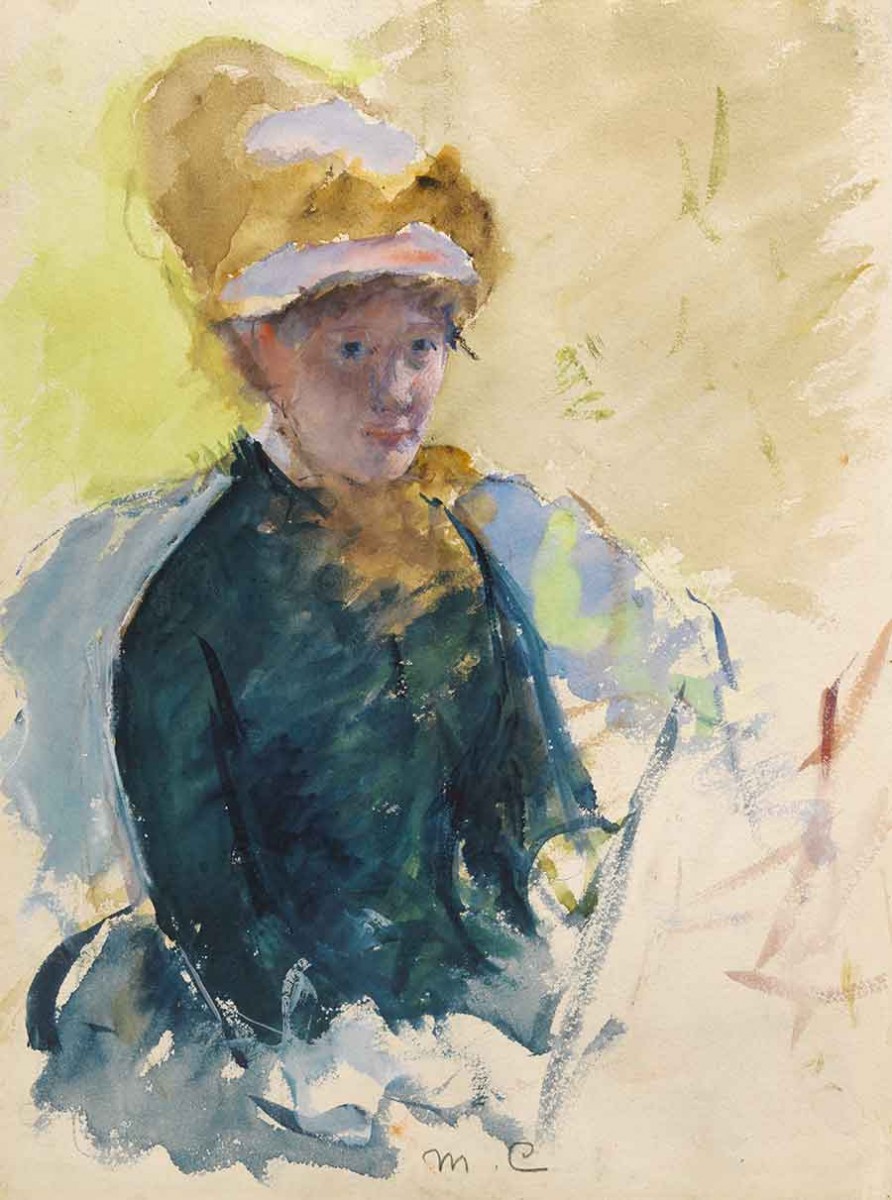

Mary Cassatt, untitled self-portrait, ca. 1880, gouache and watercolor on graphite paper, 12 7/8 x 9 11/16 in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Both women led unconventional lives in their own ways: Arabella because of the wealth and power she commanded despite her impoverished and “improper” background, and Cassatt because she eschewed marriage and motherhood. Finally, regardless of their “idiosyncrasies,” the two were prominent tastemakers in Gilded Age society: Arabella through her collecting and Cassatt through her advising. In fact, it seems possible the patroness could have solicited the artist’s expertise had Cassatt not already been aiding Louisine Havemeyer, who was one of Arabella’s biggest rivals in the art market. One wonders if they knew each other, though there is nothing on record.

Cassatt died two years after Arabella, still living in the village where she portrayed Françoise. Contemporaries claim the entire town attended her funeral. One further wonders, then, if—after 26 years, a World War, the 1918 flu pandemic, and the complexities of life in general—Françoise attended the funeral to say goodbye.

Lily Allen is a research associate in American art at The Huntington.