The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

“This reading of Books is a pernicious thing”

Posted on Tue., April 13, 2021 by

Brochure advertising The Huntington Library’s Women’s Studies seminars in the 1980s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1984, The Huntington organized and hosted the first of a series of meetings of local feminists. As a brochure in the Library’s archives explains, these seminars, scheduled to take place five times a year, aimed to “further academic research on material by and about women and to foster awareness and increased use of the resources of the Library.”

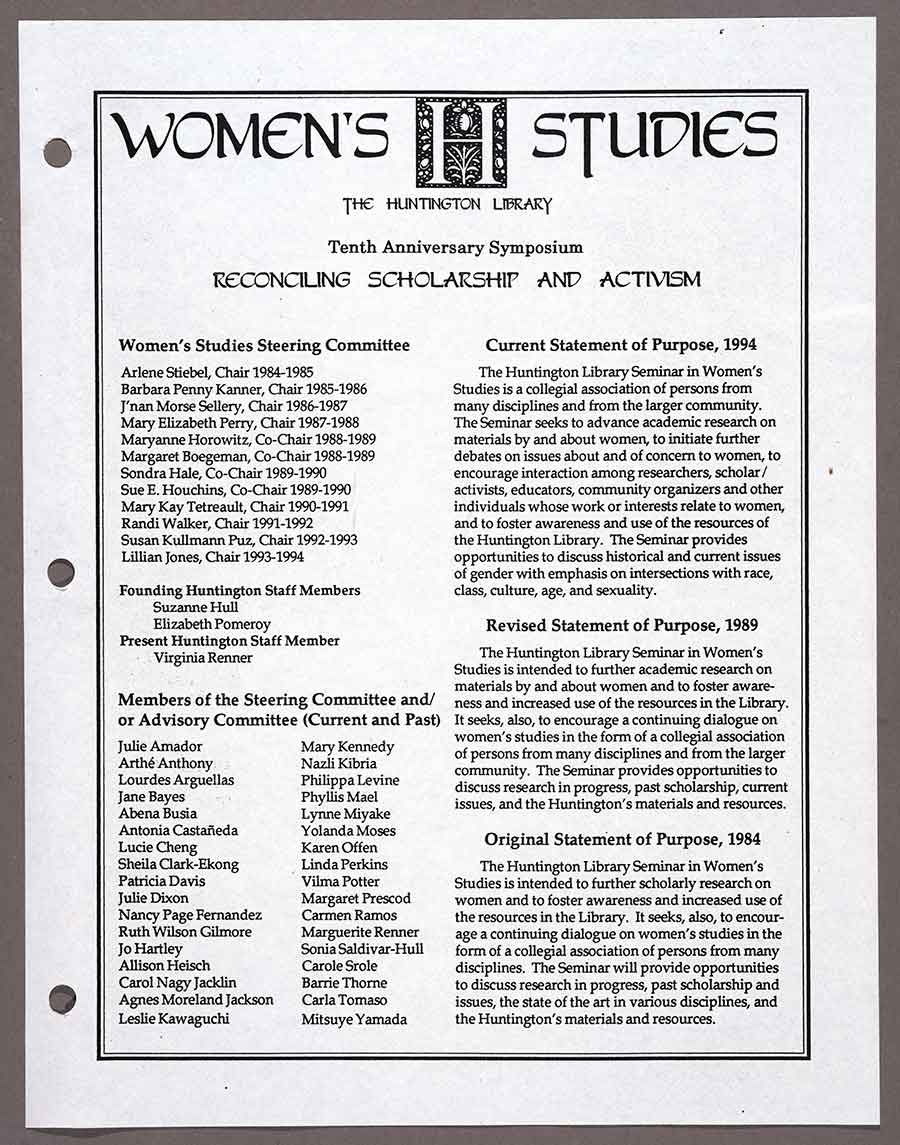

By the time of the 10th Anniversary Symposium in 1994, the network had grown into “a collegial association of persons from many disciplines and from the larger community,” meeting to explore “historical and current issues of gender with emphasis on intersections with race, class, culture, age, and sexuality.” The flyer for that 10th Anniversary Symposium included a list of the Steering Group members that reads like a Who’s Who in Women’s Studies in disciplines that ranged from anthropology to history, geography to English, and beyond: Arthé Anthony, Mitsuye Yamada, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Karen Offen, and a host of others equally distinguished.

I wish I could say that I was at those meetings, but as a young British academic, I had neither the resources nor the time to travel to California from the United Kingdom. I had regular reports, though, of what was going on from two Huntington staff members, Suzanne (Sue) Hull and Virginia (Ginger) Renner. For the 1982–83 academic year, I spent time at The Huntington on a Harkness Fellowship, researching in the Library’s fabulous holdings of 17th-century women’s writing in English.

Statement of Purpose of The Huntington Library’s Women’s Studies Symposium in 1994. Members of the Steering Committee were leading figures from across disciplines. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Throughout that year, Sue, Ginger, and I met regularly for lunch, when their Library commitments—as head of Reader Services (Ginger) and director of Administration and Public Services (Sue)—allowed. When they were free, others joined us, especially Elizabeth Pomeroy and Jan Sellers Krischke. We called ourselves the Shocking Pinks—marking our feminist agenda by wearing something of suitable hue—and talked about our voracious reading. In my last weeks of Huntington joy, Sue and Ginger swore that they would establish something at the Library that would take those conversations forward, and that they would keep me informed. The Library now has plans to digitize the tape-recordings of the papers presented at the symposia. I shall be listening, at last.

I am delighted now to be back at The Huntington—even if only virtually, in these pandemic days—coordinating a two-day conference, taking place from April 15–16, that centers on the reading of women’s writings of the late 17th and early 18th centuries: “This Reading of Books Is a Pernicious Thing: Restoration Women Writers and Their Readers.”

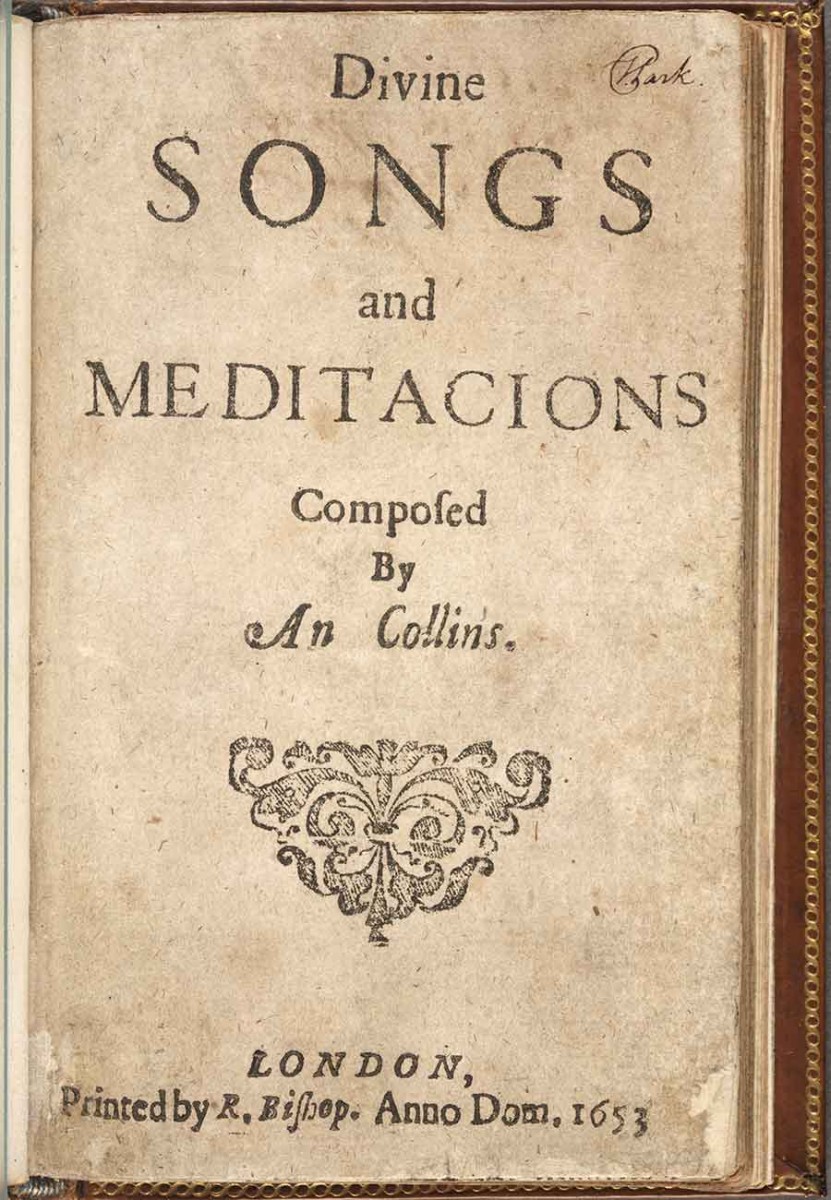

Title page of The Huntington Library’s copy of An Collins, Divine Songs and Meditacions (1653), the only copy known to still exist. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Almost exactly 40 years ago, I was planning three months of travel in the United States, setting off in New Jersey and driving to California via the Black Hills, the Rockies, Seattle, the Oregon shoreline, and San Francisco. Knowing that The Huntington owned the only surviving copy of An Collins’s Divine Songs and Meditacions (1653), I sent a letter to the Library asking to see the book, and Sue Hull, as she became known to me later, the director of administration and public services at the time, wrote back saying that I could and inviting me to lunch. As we ate, she suggested that what my research really needed was library time. Though I had to return to the East Coast to pack up my belongings, for the next year, The Huntington was my home, the crucible of the research that is my life. The reading of books was indeed for me a wicked thing—in a slang sense of “wicked,” of course.

The latest manifestation of those long-ago days, The Huntington’s conference on Restoration women writers and their readers will bring together scholars from across the U.S., U.K., and Ireland. They will discuss their current research on the women writers of the period from 1660–1720, focusing in particular on how those women’s works have been read and performed.

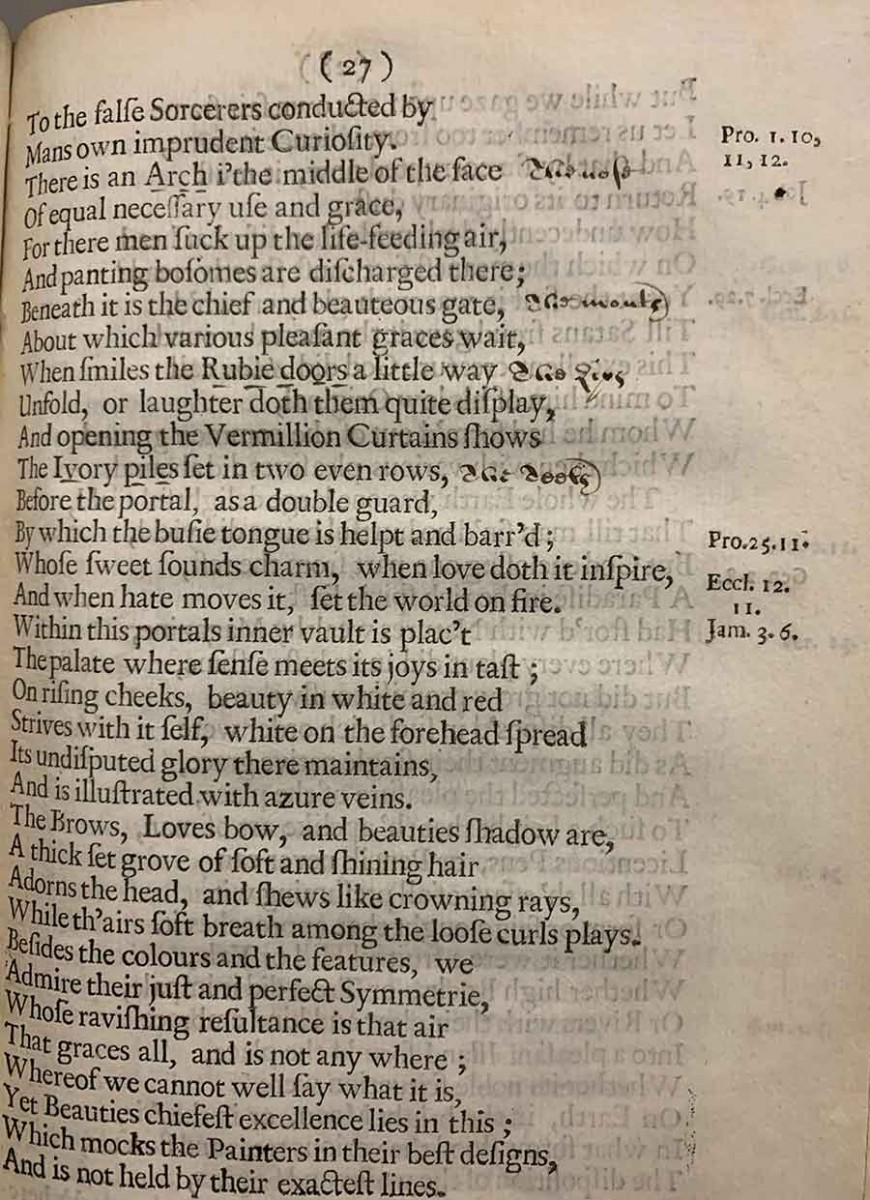

Early handwritten annotation on The Huntington’s copy of Lucy Hutchinson’s Order and Disorder. The annotation glosses metaphors in the poem as meaning “The nose,” “The mouth,” “The Lips,” “The Teeth.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The first day opens by considering the perils of publication. Such dangers ranged from the conflicts between Puritan Lucy Hutchinson and the literary underground who encountered her writings in manuscript, to the Jacobite Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea, who juggled the opportunities of manuscript networking with print publication in the early 18th century. The conference speakers on those topics are David Norbrook, who is editing Hutchinson’s works for Oxford University Press, and Jennifer Keith, whose Cambridge University Press edition of Finch is almost complete. Between Hutchinson and Finch sits Aphra Behn (1640? –1689), who “made, by working very hard, enough to live on,” according to her best-known 20th-century reader, Virginia Woolf. Claire Bowditch, drawing on her extensive research as a general editor of The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Aphra Behn, will evaluate that assessment. The conference’s first day will come to a climax as Marie-Louise Coolahan, who leads the Reception and Circulation of Early Modern Women’s Writing project, and Julia Flanders, who for decades has led computational research into pre–1800 women’s writing, raise some more general questions. Coolahan will survey and evaluate evidence of who was reading these writings by Restoration women when they first appeared; Flanders will explain and assess how today’s readers can best use the potential of digital methods to explore this huge corpus.

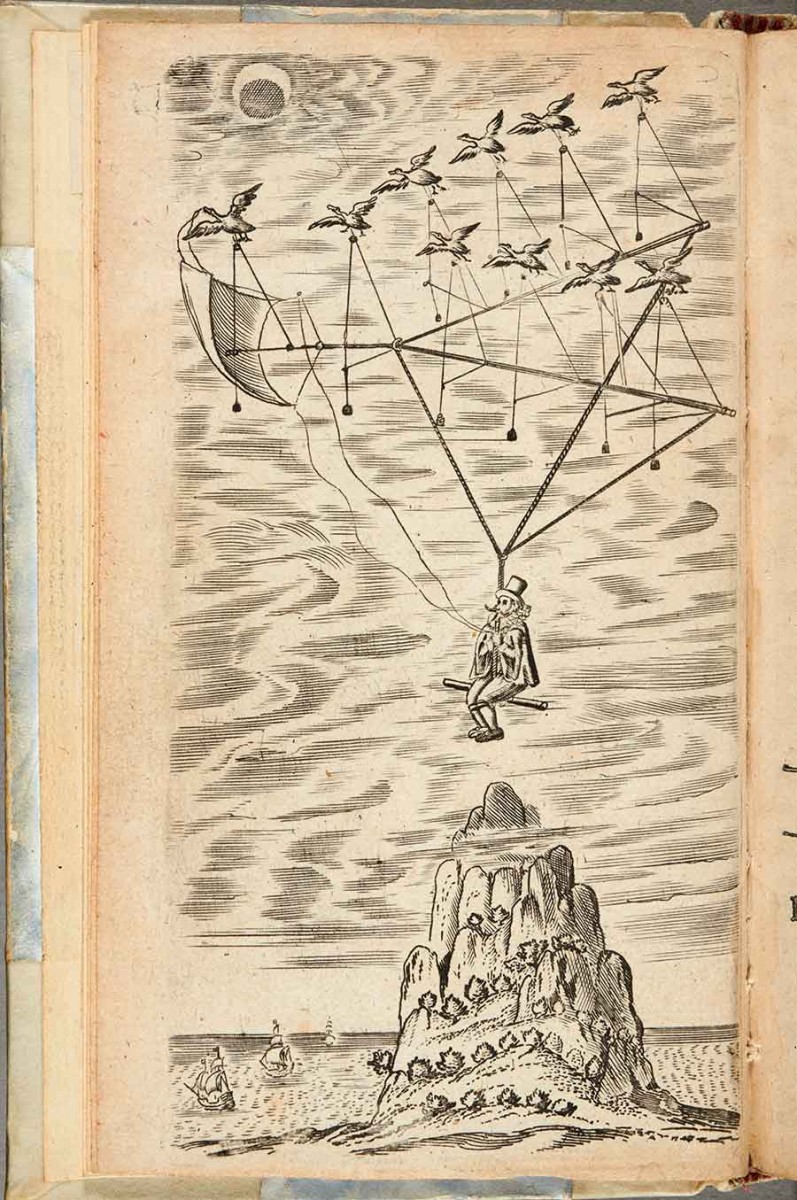

The conference’s second day, April 16, will both add to the range of writers presented on the first day, and raise further questions about what scholars are finding and how they are finding it. First, in a session titled “Plays on Stage,” we will turn our attention from reading to performance of Restoration women’s works. Joyce MacDonald, leading scholar of Renaissance and 17th-century literature and culture, will speak about her current project, which focuses on how race appears—and is sometimes erased—in Restoration drama. Providing an overview of her forthcoming Oxford University Press edition of poet and playwright Katherine Philips, Elizabeth Hageman will survey what has been discovered about Philips’s plays on stage, as well as in their manuscript and print versions. Between their talks, I will return to a writer from the first day, Aphra Behn, and explain what is at issue when a character in her play The Emperor of the Moon, asserts that “this reading of Books is a pernicious thing.”

Picture of a flying machine, powered by geese, in Francis Godwin’s The Man in the Moone, 1657, one of the books read by the lunatic Doctor Baliardo in Aphra Behn’s play The Emperor of the Moon, 1687. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The final session of the conference will focus on the readers of one of the best-known and most-disputed women writers of the period, Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle. Lisa Sarasohn, whose history of science perspective has provoked a re-evaluation of how Cavendish has been read, will analyze how the disciplinary backgrounds of today’s scholars influence their assessment of her as feminist versus anti-feminist, republican versus monarchist, or atheist versus Anglican. The final word of the formal part of the conference goes to Shawn Moore, who is leading endeavors to apply the latest digital methods to produce an edition of Cavendish’s voluminous works fit for the 21st-century’s general readers.

“This reading of Books is a pernicious thing” will be an exciting exploration of today’s research into who was reading Restoration women in the past and how we might best read them now. It will also serve as a tribute to our foremothers—to those women writers themselves, and to the feminist scholars at The Huntington in the 1980s and 1990s who worked with such energy and commitment to make these investigations possible.

Elaine Hobby is professor of 17th-Century Studies at Loughborough University. She will lead participants in a six-week Huntington U course focused on the female playwright, poet, novelist, and spy Aphra Behn. The event will be held online via Zoom at 9:30 a.m. (PDT) on April 29, May 6, 13, 20, 27, and June 3. To register, and for more information, visit the course webpage.