The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Extraordinary Expenses

Posted on Wed., June 23, 2021 by

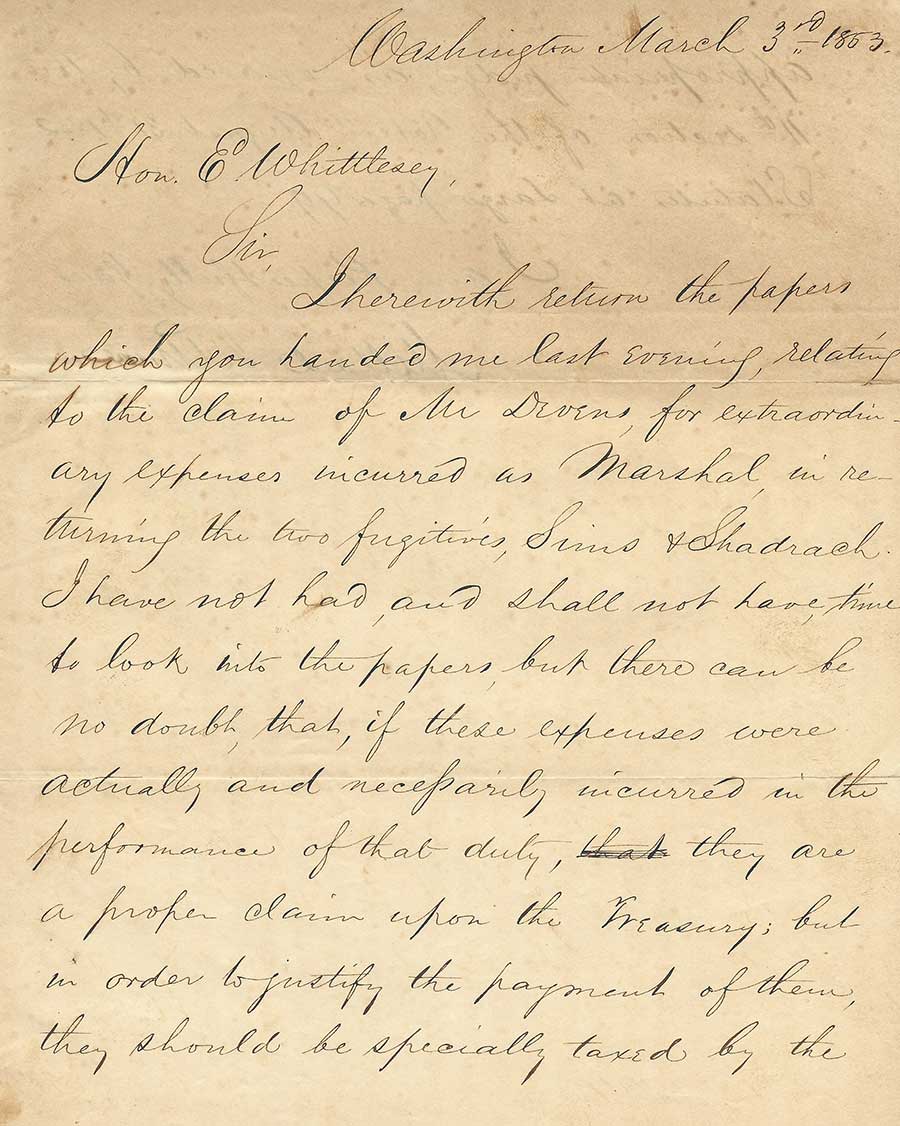

Millard Fillmore (1800–1874), first page of a letter to Elisha Whittlesey (1783–1863), First Comptroller of the United States Treasury, March 3, 1863. L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In March 1852, Charles Devens, the United States Marshal for Massachusetts, submitted an expense report. As seen in the manuscripts that have come to The Huntington as part of the L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro Collection, this seemingly mundane document sheds new light on the history of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

The law criminalized Black Americans who sought to reclaim their freedom as fugitives from justice. It categorized any assistance offered to freedom seekers as aiding, abetting, and harboring a criminal. It also placed courts at the service of the enslaver. Federal courts and their officers—judges, special commissioners, and U.S. marshals—were tasked with issuing and executing arrest warrants for "fugitives." Although slave catchers were required to bring their "reclaimed property" to court, no "testimony of such alleged fugitive" was admitted as evidence. The court's sole purpose was to make sure that the enslaver's paperwork was in order.

In Massachusetts, where slavery was outlawed in 1783, the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was met with sustained resistance. Yet the supremacy of federal law over state law meant that the Commonwealth's federal judiciary became engaged in re-enslaving their fellow citizens.

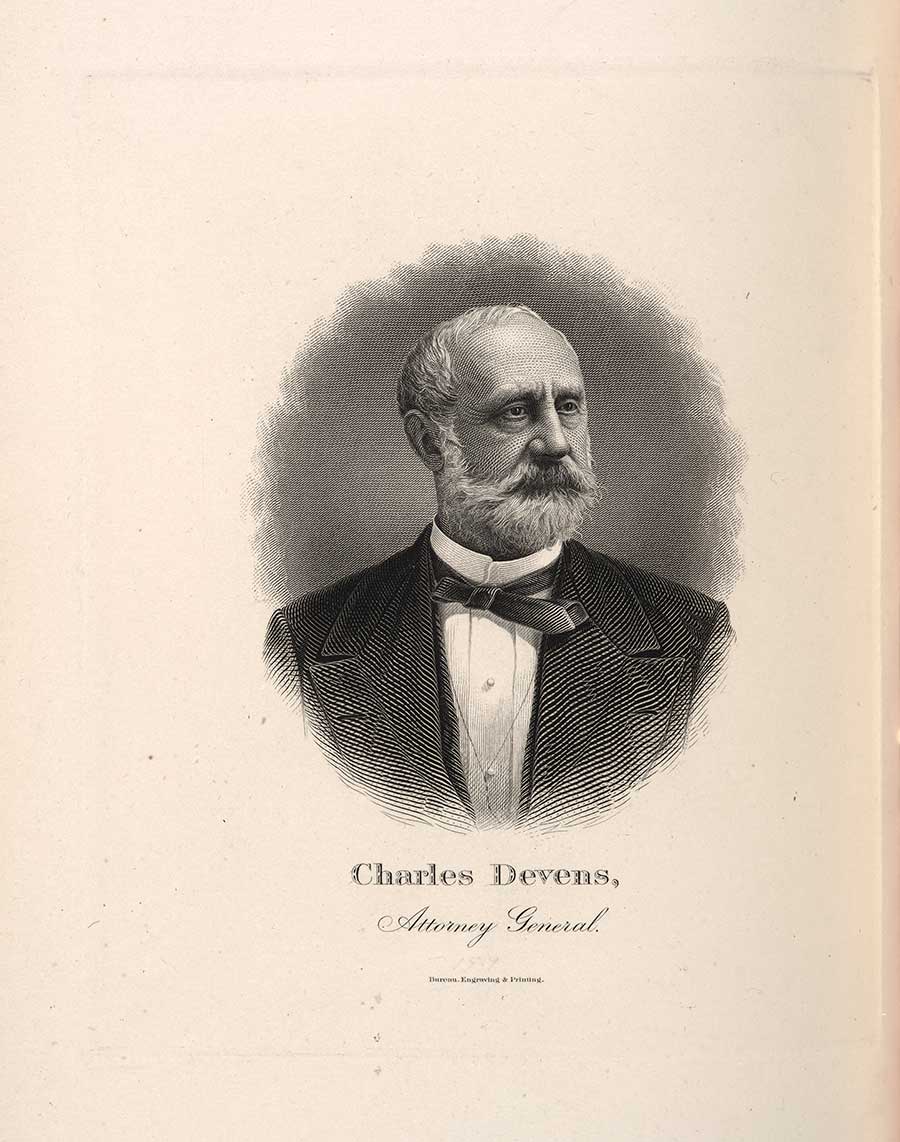

This is how Charles Devens (1820–1891), a 30-year-old Harvard graduate who had been appointed U.S. Marshal for Massachusetts in 1849, found himself at the head of the slave-catching operation in the abolitionist stronghold of Boston.

Sworn to uphold U.S. law, Devens was in a difficult position. The Fugitive Slave Law threatened any U.S. marshal who refused to accept or serve an arrest warrant for a “fugitive,” or “use all proper means” to arrest one, with a $1,000 fine—equivalent to more than $34,000 today. He was also liable to be sued for damages by the enslaver, should a “fugitive” escape while under his custody.

By all accounts, Devens did his best to resist the law. In October 1850, less than a month after President Millard Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Act, Devens refused to execute the warrant for the arrest of Ellen and William Craft, a Georgia couple famous for their daring escape from bondage in 1848. He happily accepted an abolitionist lawyer's argument that "fugitive slave" cases fell under civil rather than criminal law, meaning that Devens had no authority to use force to arrest the Crafts in their home.

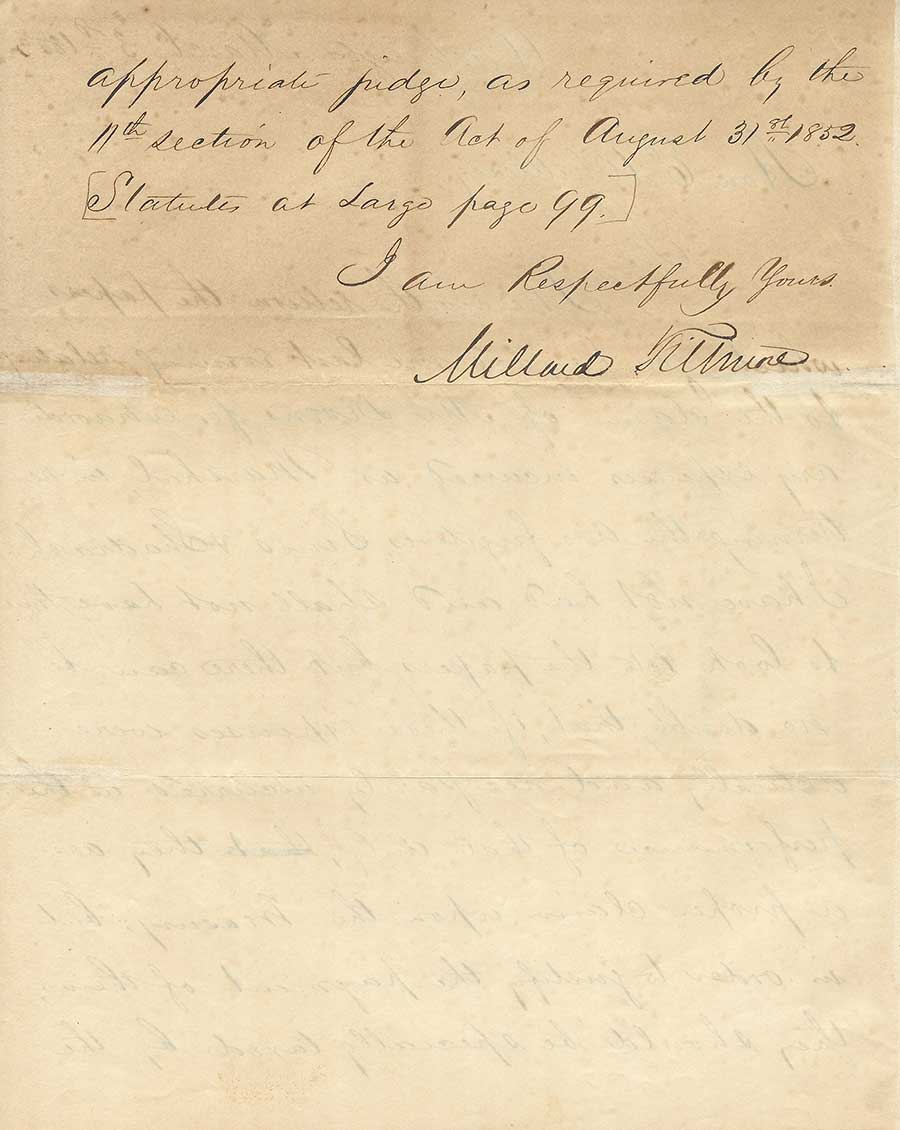

Millard Fillmore (1800–1874), second page of a letter to Elisha Whittlesey (1783–1863), First Comptroller of the United States Treasury, March 3, 1863. L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A month later, when another enslaver offered Devens a $200 finder’s fee for the arrest of a Virginia woman, Devens instead warned her and her husband and put them in touch with the abolitionist attorney Robert Morris, the first Black man to be admitted to the Massachusetts bar.

The enslavers complained to President Fillmore, and Devens was summoned to Washington to explain himself.

He was still in the capital on Feb. 12, 1851, when an arrest warrant was issued for Shadrach Minkins of Norfolk, Virginia. Minkins was arrested by Devens’s deputies. After the court rejected the writ of habeas corpus submitted by Minkins’s attorneys, a group of activists led by the African American abolitionist Lewis Hayden forcibly freed the man and sped him off to Canada.

In March 1851, Devens—back in Boston and citing a severe storm—canceled a mission to New Bedford to apprehend “fugitives” there.

However, the U.S. marshal was running out of options. Southern enslavers were complaining that the Fugitive Slave Law was not being enforced in the North, and the Fillmore administration was determined to make an example out of Boston.

The case of Thomas Sims, a young bricklayer from Georgia arrested in Boson on April 5, 1851, provided an opportunity.

Devens had no choice but to execute the arrest warrant. In a long-shot maneuver contesting the arrest based on something known as a writ of personal replevin, Sims's lawyers tried in vain to convince Devens to release Sims—ultimately to no avail, as the writ they cited did not apply to the situation.

Charles Devens (1820–1891). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

On April 11, Devens supervised a heavy guard that surrounded Sims as the court pronounced the young man a “chattel personal.” According to Devens’s son, the marshal “spared no pains” in a last-ditch attempt to buy Sims’s freedom. He failed. Sims was shipped to Georgia and then on to an auction block in New Orleans.

In March 1852, Devens submitted the report of the “extraordinary expenses” incurred during the arrest of Minkins and Sims. As seen from the letters in the Shapiro Collection, the expenses were indeed extraordinary, totaling $7,187.55—almost $250,000 in today’s money.

The First Comptroller of the Treasury, taken aback, reported Devens’s claim to President Fillmore. The president doubted that “these expenses were actually and necessarily incurred,” suspecting that Devens, in yet another act of resistance, had padded his expense report.

It is hard to say whether he did. The Fugitive Slave Law specified that a U.S. marshal and his deputies were entitled to a fee of $10 for any detainee returned to their enslaver. Those who assisted the U.S. marshal in their slave-catching duties were entitled to five dollars a head. For example, the 200 policemen and 100 law-abiding citizens of Boston who had volunteered their services to march Sims to the Long Wharf on his way back to enslavement would have cost the Treasury some $1,500, or one-fifth of the sum listed in Devens’s expense report.

The expense of recovering "fugitive slaves" was often cited as evidence that, after 1851, the federal government was reluctant to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law. Yet, in the end, the Treasury was perfectly happy to pay Devens’s “extraordinary expenses,” and the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law continued with its brutal efficiency until it was repealed by an Act of Congress on June 28, 1864.

Devens and Sims met again. In 1877, Devens, who had become the U.S. Attorney General, offered the man he had returned to enslavement a messenger's job at the Department of Justice. Sims accepted.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.