The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Queer Artist, Queer Courage

Posted on Wed., June 16, 2021 by

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, 1859, marble, height: 82 × 27 × 33 in. (208.3 × 68.6 × 83.8 cm). Purchased with the Virginia Steele Scott Acquisition fund for American Art. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

I honor every woman who has strength enough to step outside the beaten path when she feels that her walk lies in another. — Harriet Hosmer

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830-1908) unapologetically pursued her ambitions as a sculptor in a field considered inappropriate for women and lived openly as a lesbian during a time of constricted female roles.

She influenced generations of women artists while earning great success and acclaim throughout her career. Her masterpiece, Zenobia in Chains (1859), created when she was just 29, is one of the most famous and controversial objects produced during the “golden age” of American classical sculpture in the mid-19th century. The seven-foot-tall marble sculpture depicts the third-century queen of Palmyra (now Syria) captured by a Roman emperor and paraded through the streets in chains. Since 2009, Zenobia in Chains has graced The Huntington's Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art.

“For Hosmer, Zenobia represented a counterculture heroine who bucked gender norms and offered a model of strong female leadership,” says Dennis Carr, The Huntington's Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art. “The dignified, clothed statue is Hosmer’s own commentary on the fear of female power,” he adds.

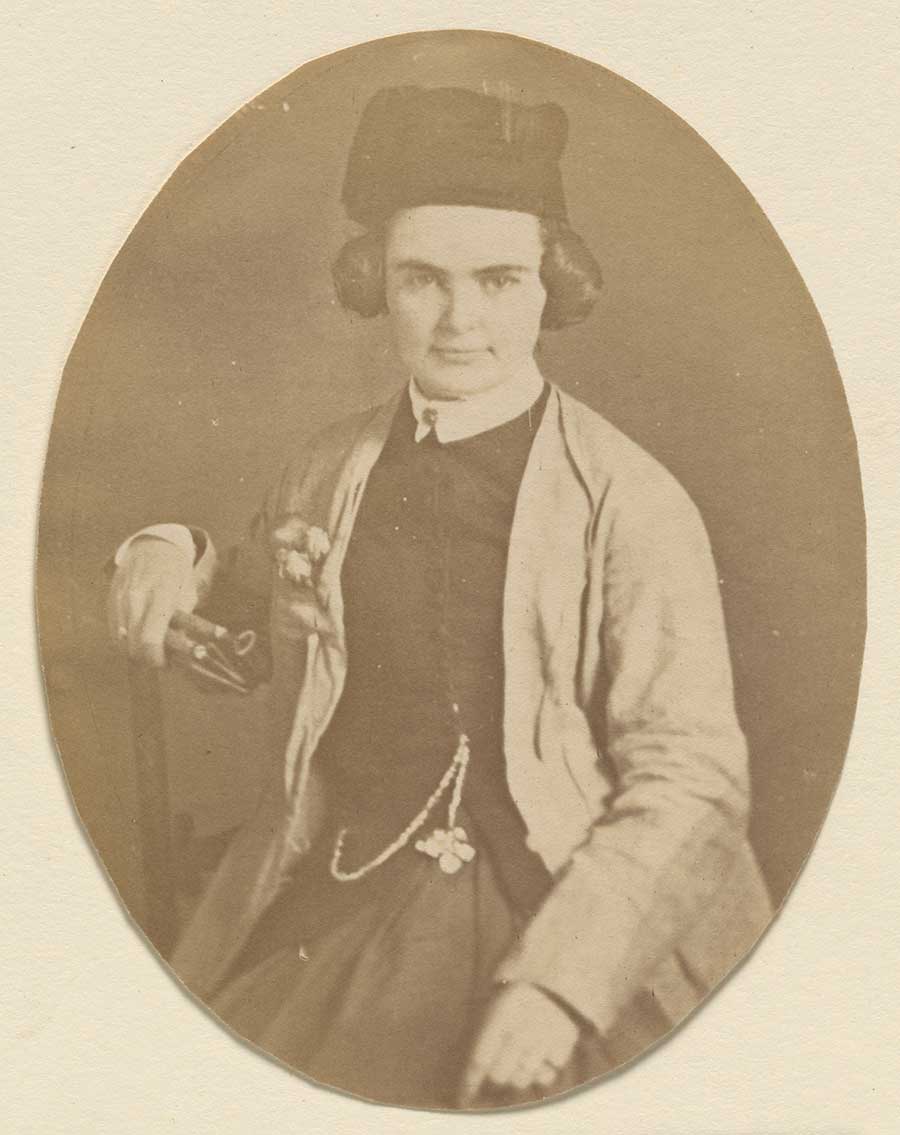

Unknown photographer, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, ca. 1855, salted paper print, 6 1/8 x 4 11/16 in. (15.5 cm x 11.9 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Throughout her career, Hosmer often depicted idealized mythological figures, especially female characters known for their strength and courage. In this way, she used her artwork as a means of critiquing the social position of women in 19th-century culture.

Hosmer’s life, like that of Zenobia, was defined by rebellion. After deciding at 19 to become a sculptor, a profession in 19th-century America claimed only by men, Hosmer moved in 1852 from Watertown, Massachusetts, to Rome, Italy, to pursue her ambition. There she found a more tolerant atmosphere for an independent woman and lesbian. For many years, she thrived in her community of expatriate female artists and writers who defied 19th-century expectations to find artistic companionship and inspiration and, if they desired, openly queer relationships.

"It is perhaps somewhat hard to judge how 'open' she was about her sexuality in today's terms, but there are a number of period descriptions of Hosmer and her creative circle," says Carr.

He likes to point people to a quote by the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who met Hosmer in Rome, and which provides a candid account: "[Hosmer] was very peculiar, but she seemed to be her actual self, and nothing affected or made up; so that, for my part, I gave her full leave to wear what may suit her best, and to behave as her inner woman prompts."

Sir William Boxall, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, 1857, 35 13/16 x 27 15/16 in. (91 x 71 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

When Hosmer showed Zenobia in Chains in 1862 at the International Exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace to critical acclaim, she was accused of attempting to pass off a man’s work as her own. A work of such sublime expression, on such a grand scale, that required power of hand and arm in the carving, could not be created by a woman, her male critics argued.

By forcefully defending her work as her own through a libel suit against publications that ran stories claiming otherwise, and by demanding her rightful recognition in public through her own writing, Hosmer established women as equals to men in the traditionally masculine medium of sculpture.

After the London exhibition, Zenobia in Chains traveled to the United States, where it was exhibited in New York, Boston, and Chicago. Viewed by enthusiastic crowds and garnering critical praise, it was subsequently bought by a private collector.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, 1859, marble, height: 82 × 27 × 33 in. (208.3 × 68.6 × 83.8 cm). Purchased with the Virginia Steele Scott Acquisition fund for American Art. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Then an occurrence took place that might not have surprised Hosmer, who knew how hard it was to stay visible and relevant. The sculpture fell from sight in the art world. When it resurfaced at a Sotheby’s auction in London in 2007, it hadn’t been seen publicly for more than 100 years. That’s when The Huntington acquired the piece.

Today Hosmer’s statue of Zenobia commands attention and admiration in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art at The Huntington, serving as a towering reference point amid provocative contemporary work in the current “Made in L.A. 2020” exhibition. A groundbreaking artist who lived with great courage in her time, Hosmer continues to serve, through her masterpiece, as an inspiration in ours.

Manuela Gomez Rhine is a freelance journalist based in Pasadena, California.