The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Monster in the Mirror

Posted on Wed., July 7, 2021 by

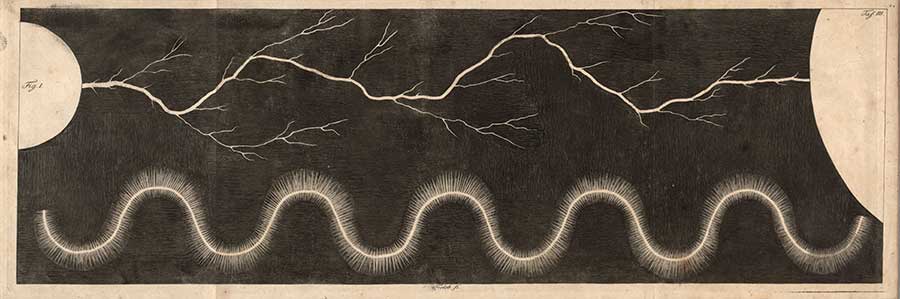

Martinus van Marum, Beschreibung einer ungemein grossen Elektrisier-Maschine (Description of an Unusually Large Electrostatic Machine), Leipzig, 1786, plate 3, "Lightning effects produced by an electrostatic generator." The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The Dutch chemist Van Marum became known for his spectacular public demonstrations of electricity. A later experimenter in electricity, Giovanni Aldini, may have inspired Mary Shelley with his application of electric shocks to human corpses.

What sparks the lightning bolt of insight? How do we come to see with new eyes?

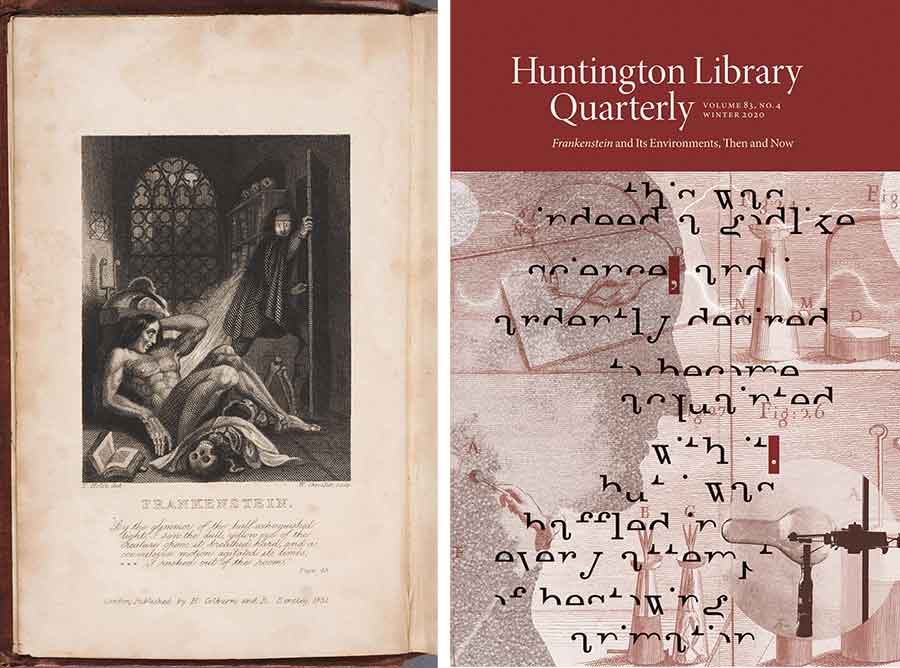

Literature can expose us to perspectives strange to us, but our interpretations can also be clouded by familiarity. We think we know the story of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein and its adaptations—after all, it is one of the ubiquitous works in English and the most frequently assigned work of fiction at colleges across the United States; its lines have been traced by millions of bleary undergraduates. A special issue of the Huntington Library Quarterly, “Frankenstein and Its Environments, Then and Now,” edited by Jerrold E. Hogle, emeritus professor of English at the University of Arizona, seeks to make it new again, revealing aspects that were there all along but never before seen.

Left: Frontispiece from the third edition of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s gothic novel Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus, 1831. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The engraving on the frontispiece, produced by William Chevalier from a drawing by the British artist Theodor von Holst (1810–1844), is the first known visualization of Victor Frankenstein and his creature attached to an edition of the novel itself. Right: Cover of the HLQ special issue, “Frankenstein and Its Environments, Then and Now.”

For example, one contributor, Maisha Wester of Indiana University, noticed that Victor Frankenstein speaks of himself as a “slave” of his monstrous creation. As she points out, this seems downright peculiar. Earlier scholars of the novel have shown that Shelley’s descriptions of the creature and his cruel treatment closely echo portrayals of enslaved Black people in antislavery tracts of the period. Victor, by contrast, is a wealthy, educated white man whose physical and intellectual liberty seems without limit—he has, after all, made himself a god.

So why does Victor complain that he is a slave? Following up on her canny observation, Wester discovers that Victor shares the self-image of many British enslavers of Shelley’s time—at least one of whom, Matthew Lewis, she knew personally. Enslavers resisted the thought of emancipation, for fear of the violent vengeance that enslaved people might justly wreak. Some enslavers—knowing they were wrong but afraid to embrace abolition—saw their own implication in the terrible cruelty of slavery as itself a metaphoric enslavement.

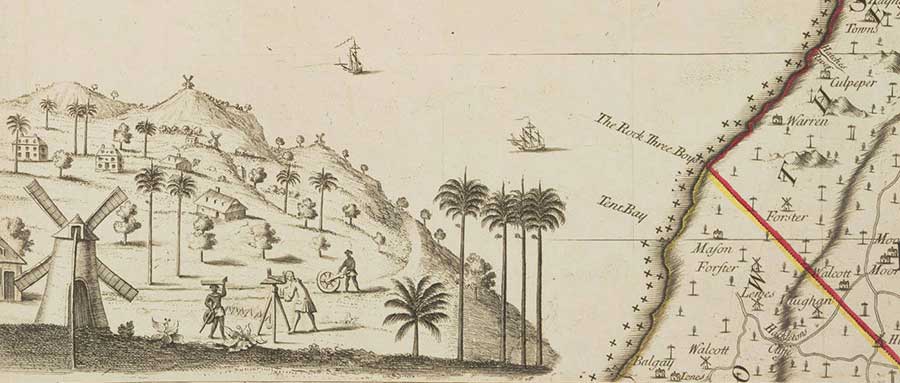

William Mayo, detail from New and Exact Map of the Island of Barbadoes in America, According to an Actual and Accurate Survey made by William Mayo, ca. 1796. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. In 1816, the year that Mary Shelley began writing Frankenstein, enslaved people rose up against plantation owners in Barbados, a British colony at the time. The viewer of the map sees the land from the perspective of a European surveyor, whose back is turned to us, rather than from the perspectives of the Black men who gaze back at us. The map is dedicated to James Brydges, Duke of Chandos, who was part-owner of a plantation in Jamaica and an enslaver .

Thus, the novel reflects the 19th-century cultural debate over the responsibility of enslavers for the actions of the people that they enslaved. That responsibility was highlighted by a series of widely reported rebellions by enslaved people, including one in the British colony of Barbados in 1816 known as Bussa’s Rebellion. Wester concludes: “Frankenstein ultimately turns us to the question of who the real monster is: the Creature, who, having been brutally rebuffed in his hope for compassion, reacts violently to painful social oppression and marginalization, or the master who created him only to mistreat and neglect his creation because of his prejudices—or is the greater monstrosity the oppressive cultural assumptions that produced both of them?”

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Saint Goarhausen and Katz Castle by Moonlight, 1817, watercolor with scraping out on wover paper, 7 1/2 x 12 1/8 in. (19.1 x 30.8 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Some think the moody landscapes of this period (including the extraordinary effects of light in J.M.W. Turner’s works) are not merely impressionistic. Instead, they may bear witness to the haze that hung between the Sun and Earth in the years after the eruption of Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa in April 1815.

As Wester’s arguments show, aspects of Frankenstein that appear to be merely symbolic may reflect palpable historical concerns—including those that are strikingly relevant today. The novel’s cold, stormy, lightning-blasted scenes, for example, can feel like a cliché of gothic atmosphere. But, as Gillen D’Arcy Wood notes in his essay, the novel was composed in the midst of the climate catastrophe known as the “year without a summer.” The Mount Tambora volcano in Indonesia erupted in April 1815, producing extreme cold weather across the globe, mass refugee migrations driven by famine, and outbreaks of disease that lasted for several years. Shelley, from her vantage point in Switzerland, saw the starvation and misery firsthand.

Joseph Wright of Derby, Vesuvius from Portici, ca. 1774–76, oil on canvas, 39 3/4 x 50 in. (101 x 127 cm.). Purchased with funds from the Frances Crandall Dyke Bequest. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The explosion of Mount Tambora, of which there are no known contemporary depictions, is thought to be the largest volcanic eruption in human history, killing upward of 70,000 people. The eruption of Vesuvius in the year 79, which destroyed Herculaneum and Pompeii, was approximately one-hundredth its size. This painting seems to be of an imaginary eruption, as Vesuvius was not active when Joseph Wright visited Italy; Vesuvius did, however, experience major eruptions throughout the 18th century.

This context upends the idea that the creature’s solitary wanderings after being shunned by his creator are above all a retelling of the expulsion from Eden—though they are also that. The creature, in this reading, is also a figure for the suffering refugees of Europe, who were rejected as monstrous and diseased wherever they sought help. An item in the Dublin Post of 1817 railed, in terms we cannot but find familiar, against “vagrants and beggars, who have emerged from receptacles of disease, and spread themselves.” The creature calls out to our consciences from the last major climate disaster, asking how we will respond to our own.

The last year has taught us how necessary and difficult it is to change the way we look at things. Not merely timeless fonts of wisdom, classic works of literature may achieve their truest greatness by revealing new facets when we approach them with the questions of our moment. As Wood concludes of Frankenstein, “The novel is a cultural treasure, but it doesn’t belong behind glass. It’s alive, like the monster itself.”

The conference “Frankenstein Then and Now, 1818–2018” is available in audio on SoundCloud. Copies of the special number of the Huntington Library Quarterly can be ordered for $20 by writing journals@pobox.upenn.edu. A free annotated bibliography of major editions and criticism of the novel from the last decade, compiled by editor Jerrold E. Hogle, is available online at Zotero.

Sara K. Austin is editor-in-chief of the Huntington Library Quarterly, The Huntington’s scholarly journal of humanities research on the early modern period in Britain and America.