The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Migrant Experience, in Spanish

Posted on Wed., Sept. 22, 2021 by

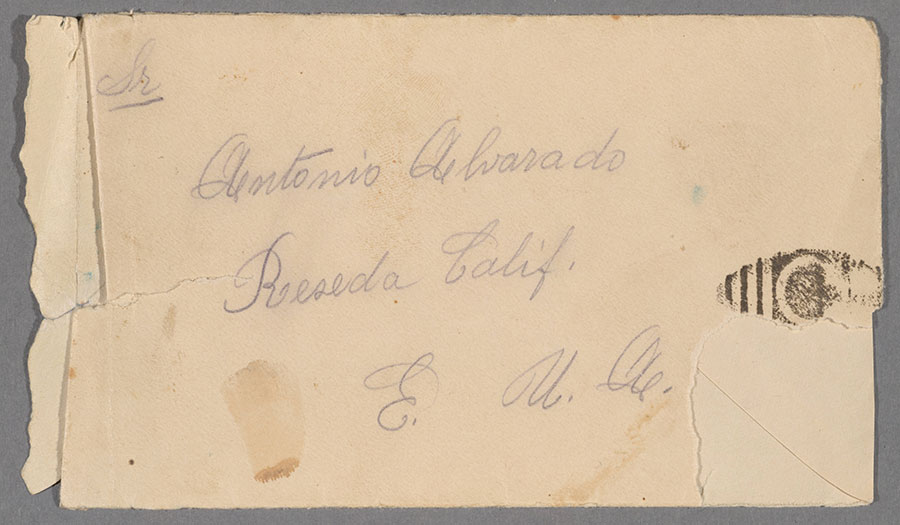

Front of the envelope of a letter from Ysidro Alvarado to his father, Antonio Alvarado, March 6, 1926. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington has deep collections on the history of Spanish-speaking North America created from a centurylong record of acquiring materials in this field. A strong and growing collecting area within these materials relates to the migrant experiences of people from Mexico and Central America.

Scholars are vigorously pursuing migration studies, eager to better understand what it means to leave a place, often under duress, and attempt to settle someplace new and often quite daunting.

There are the family letters of José Antonio Alvarado, born in 1905 on a hacienda called “La Sandia” outside León, in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. Like many others from his state, he and his parents—Clara Torres de Alvarado (d. 1967) and Antonio Alvarado (dates unknown)—made the move to the United States, in their case to Southern California, probably around 1926. And, like so many of their compatriots, his and his parents’ labor in the fields was fundamental to the success of one of California’s most important industries, agriculture.

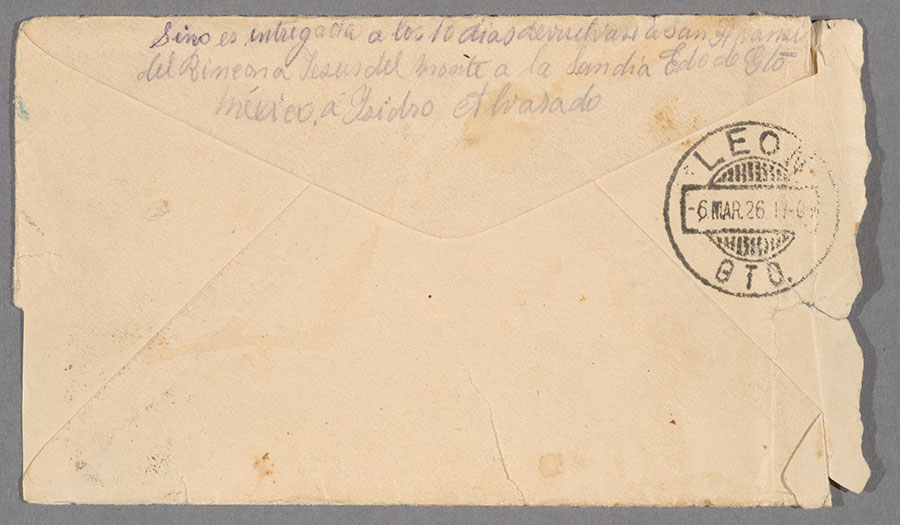

Back of the envelope of a letter from Ysidro Alvarado to his father, Antonio Alvarado, March 6, 1926. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Yet, unlike the story of many of his compatriots, that of José and his parents can be at least partially told because of the serendipitous survival of 33 family letters written between 1926 and 1954. The letters were principally written by Alvarado family members in Mexico to the three Alvarados in Southern California, where they lived first in Reseda and then in Ventura County.

For 45 years, José Alvarado worked and then lived in retirement on the Grether farms of Ventura County. There, he worked for, lived near, and became friends with Mark Moore, who left the farms in 1980. José died in 1982 without heirs; the Grether family consequently took responsibility for his possessions, including his family's letters, which, surprisingly, they did not throw away. When Moore visited the farms in the mid-1980s, the Grethers gave the letters to him because of his friendship with José. Always interested in a home where the letters would be valued, Moore was, some 30 years later, referred to The Huntington by Andrew Sandoval-Strauz, professor of history at Penn State, and Miroslava Chávez-García, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In 2019, Moore donated the letters to The Huntington.

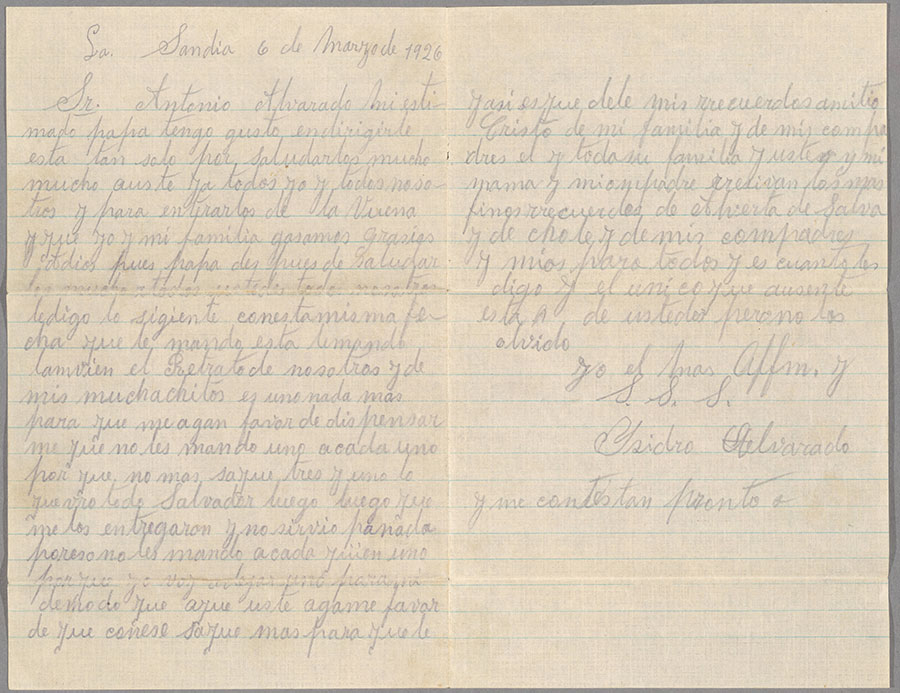

First page of a letter from Ysidro Alvarado to his father, Antonio Alvarado, March 6, 1926. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Chávez-García herself had donated her family letters to The Huntington a few years ago. She did so because the love letters exchanged by her parents and the missives exchanged among a network of close relatives across the California-Mexico border provided deep insights into the migrant experience. They served as the chief source for her award-winning history, Migrant Longing: Letter Writing across the U.S.–Mexico Borderlands (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). (You can read more about Chávez-García’s book in Huntington Frontiers.)

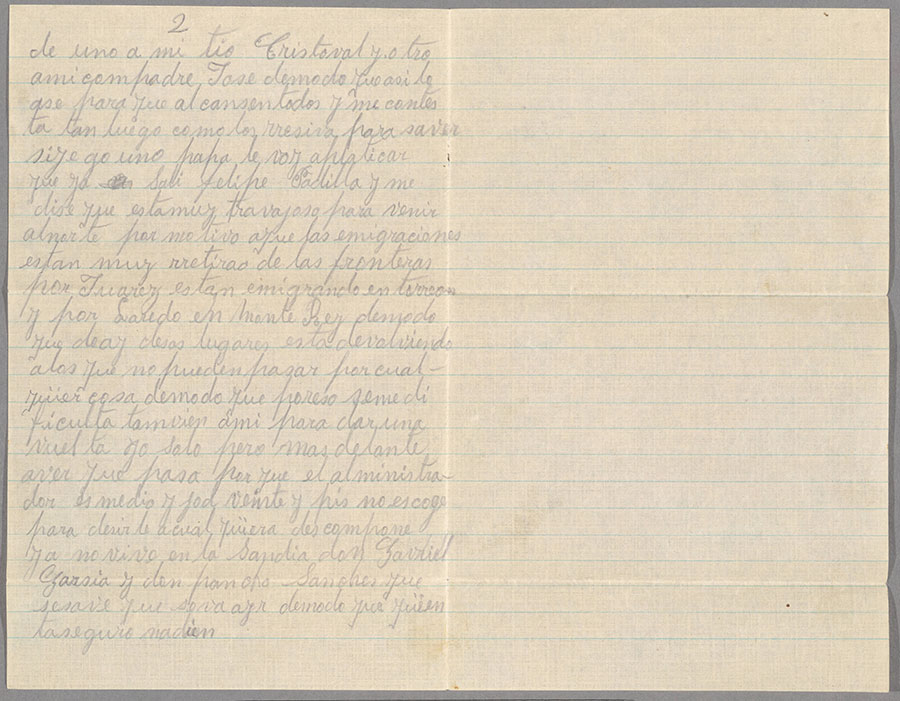

In the case of the Alvarado collection, Antonio’s son Ysidro, living in La Sandia, wrote many of the letters. Other relatives in the vicinity of La Sandia also wrote, and the collection includes letters to Antonio from fellow migrants in Southern California. The letters’ lengthy salutations, references to health, and mentions of such family milestones as baptisms speak to their sentimental value, but the letters also yield rich historical information. Dated March 6, 1926, the first letter, from son Ysidro to father Antonio, details routes of migration, in this case from León to the U.S.-Mexico border at Nuevo Laredo, and the reception once there. Ysidro refers to the United States simply as “el Norte” (the North).

Second page of a letter from Ysidro Alvarado to his father, Antonio Alvarado, March 6, 1926. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The letters also discuss other people who left for the U.S., and, in so doing, record the resulting personal loss. For example, Pascual Carpio, also of La Hacienda, laments to Antonio in his letter of Aug. 20, 1928, that his only son has left for the United States, and that Silvestra, perhaps a daughter, wants to leave as well because she needs work. Pascual wrote that he was also considering leaving to be reunited with Leonor, probably a relative, who was in Brawley, California. He relayed: “por el momento me es bastante triste” (“at the moment, I’m quite sad”).

Other details of the migrant experience pepper the letters. For example, many letters extensively refer to remittances that Alvarado family members in Southern California sent to relatives in Mexico. These remittances could be cash for general family needs as well as such specific items as shoes, perennially difficult to come by there. Sewing thread is one particularly popular item; it is mentioned at least four times in the letters. In one case, a skein of thread sent from California to Ysidro and his wife, Alberta, was used to make bibs. In a letter dated July 14, 1929, Ysidro specifically requests green thread because of its expense in Mexico. From such statements, historians can develop not only a practical understanding of migration (e.g., remittances) but also its emotional toll on people such as Pascual.

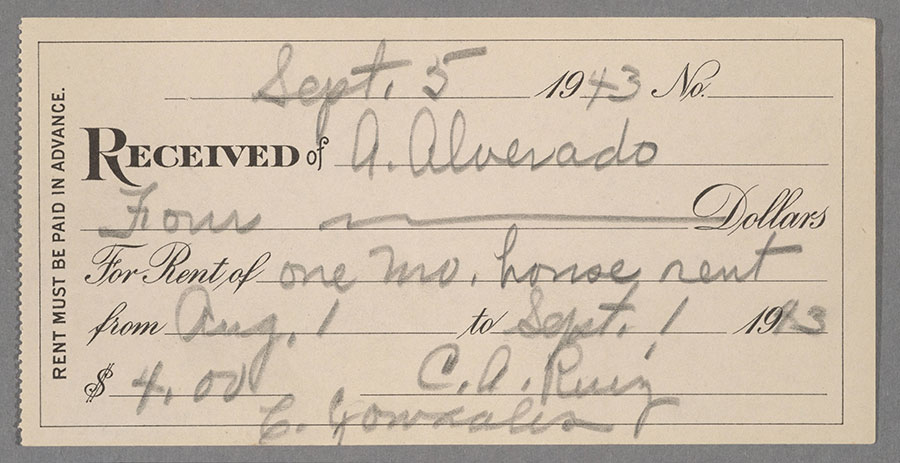

A rent receipt for Antonio Alvarado, who lived in Reseda, California, Sept. 5, 1943. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Alvarado letters, with their firsthand accounts, speak deeply to the personal experience of migration, which is what The Huntington seeks to preserve through these types of materials. Unfortunately, such letters are rare in archival repositories and libraries. Collections here that help remedy this lacuna include the memoirs of Fernando Quirós Castro, who came to Los Angeles from Costa Rica in 1944. His writings detail the route he took, acknowledge support he received from the Costa Rican community of Los Angeles, and chronicle his development of an engineering firm in Southern California before his return in 1974 to Costa Rica. Such first-person testimony of people migrating from Central America to the United States is extremely rare in archives, making this source invaluable.

Chávez-García has written eloquently about the historical and cultural importance of such collections: “Personal letters such as these are invaluable because of their ability to convey both well-known as well as obscure historical, cultural, and personal insights. The correspondence provides a window into the social, economic, cultural, and political developments of the day, whether in and across Mexico and the United States or beyond. The letters, as I have found in my effort to map my family’s history, reflect the hopes and dreams as well as fracasos (failures) of those who sought to improve their lives—and the lives of those they left behind—by migrating to el Norte (the North). Indeed, the missives provide a wealth of insight on migratory processes, social networks, and individual relationships in alleviating migrant longing for bridging aquí (here) and allá (there).”

For these reasons, The Huntington seeks to help preserve this vital part of the history of California, the U.S., and North America.

Miroslava Chávez-García, professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of Migrant Longing: Letter Writing across the U.S.–Mexico Borderlands (University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

You can listen to Chávez-García and others speak on this topic in The Huntington’s Hear and Now podcast, “Letters across the Border.”

Clay Stalls is the curator of California and Hispanic Collections at The Huntington.