The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

“To Influence the Minds of the People”

Posted on Thu., Feb. 17, 2022 by

Engraving by John Rogers (ca. 1808–1888), after the painting by Michael Angelo Wageman (ca. 1820–1898), ca. 1850. George Washington (1732–1799) presiding over the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1968, the third Monday of February was designated Presidents Day—a U.S. national holiday celebrating all presidents, past and present. The choice of the date was tied to Feb. 22, George Washington’s birthday, which had already been set as a holiday for federal workers in 1885.

The choice of the date was obvious. The first U.S. president had long been celebrated as the Father of His Country, the title which echoed the Roman title pater patriae bestowed on heroes and emperors.

In 1861, Jefferson Davis chose Washington’s birthday as the date of his inauguration as the president of the Confederate States of America. On Feb. 22, 1862, amidst the Civil War, the United States Senate and the House of Representatives met in a joint session to read Washington’s Farewell Address (1796), a paean to the “unity of government” that made Americans “one people,” with its solemn warning “against the baneful effects of the spirit of party.” The Senate continues the tradition of reading the address annually on Feb. 22.

Over the years, Washington’s image has lost some of its luster. He consistently tops historical rankings of U.S. presidents, but he also is consistently rated the most racist U.S. president in the American Politics and the African American Quest for Universal Freedom poll.

Yet Washington is still invoked as the gold standard of civic leadership, due in large part to the way he successfully presented himself as a sage who eschewed “the strongest passions” of personal ambition to remain above the political fray.

This ideal was imprinted in the nation’s imagination in the image of Washington solemnly presiding over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

But the framers of the Constitution, including Washington, were mere humans who, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, brought “all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views” to the proceedings.

Washington, a staunch Federalist who firmly believed that only a strong federal government could ensure the unity and prosperity of the American nation, did not hesitate to use his enormous influence to advance the cause. This influence became critical during the ratification battle that decided the fate of the Union.

Engraving from Charles A. Goodrich’s A History of the United States, 1824. George Washington (1732–1799) presiding over the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Washington shared Franklin’s view that the Constitution was “nearly perfect” and envisioned a smooth, speedy, and unanimous ratification. His hopes were soon dashed.

Article VII of the U.S. Constitution declared that “the Ratification of the Conventions of nine States” was “sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States.” However, the ratifying states had no power to impose their decision on other states. In other words, the states that refused to ratify the Constitution would, for all intents and purposes, remain outside the Union.

The fierce, bitter, and highly partisan debates over the Constitution followed fault lines that may look ominously familiar today. The divisions between federalists and antifederalists also pitted North against South, East against West, and what was then known as the “backcountry” (now called the “heartland”) against coastal cities and towns.

Some demanded a national government that would protect American commerce, assert the republic’s international standing, and, if need be, defend it against foreign invasion. Others feared new taxes and intrusions of a distant federal government. The champions of individual liberties hurled charges of tyranny at those who prioritized the nation’s well-being, only to be accused of fostering anarchy.

In this fight, the federalists enjoyed clear political advantages. Commanding a disproportionate share of the nation’s wealth, they exercised political influence over state legislatures, the press, and society at large. They also had Washington on their side.

After Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut voted for ratification, events took an alarming turn. On Feb. 6, 1788, the Massachusetts convention, defying the forecasts of an easy ratification, approved the Constitution by a razor-thin majority and only after concessions were made regarding future amendments.

The Bay State, still reeling from 1786 tax protests, could be dismissed as a fluke. The next New England state to vote was New Hampshire. John Langdon (1741–1819), the former New Hampshire governor and signer of the Constitution, assured Washington that the entire state clamored to have the Constitution ratified “as soon as may be.”

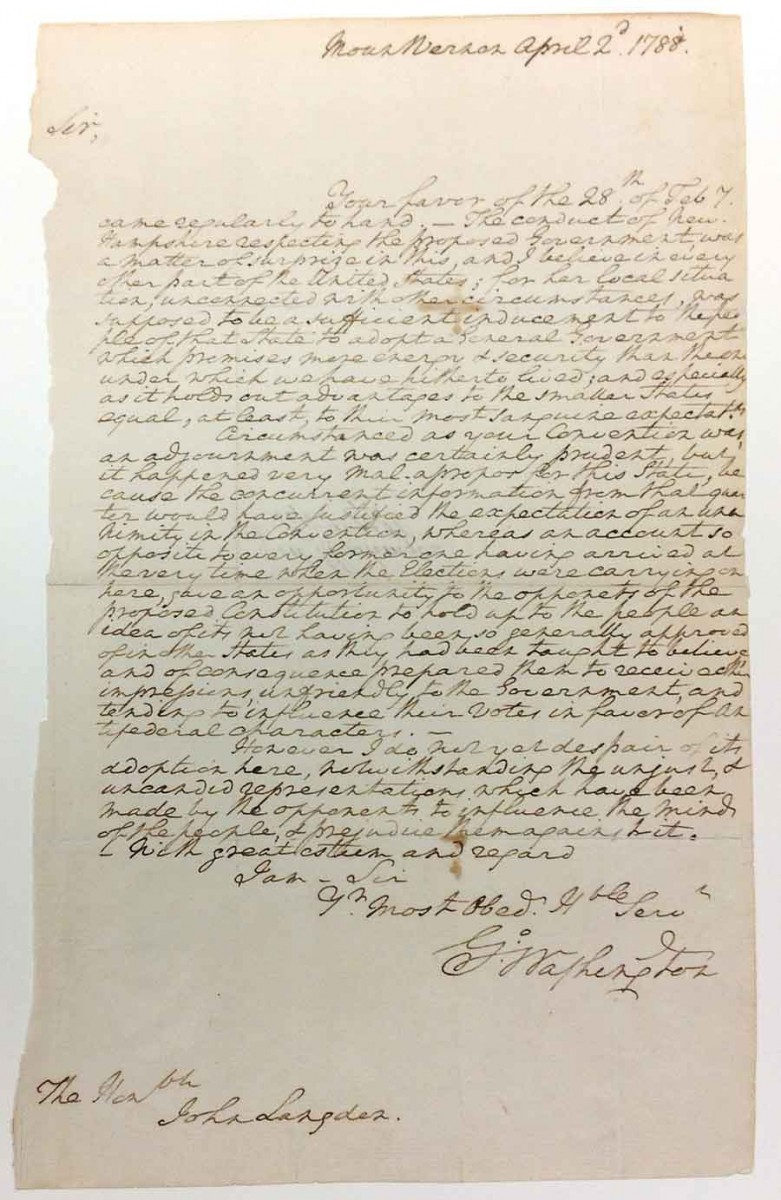

George Washington (1732–1799), autograph letter, signed, to John Langdon (1741–1819), April 2, 1788. The Shapiro Collection. Promised gift of L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Writing to his friend John Langdon, Washington expressed his dismay over the “incomprehensible conduct” of New Hampshire’s failure to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

Then came the blow. On Feb. 28, 1788, the shaken Langdon informed Washington that “contrary to the expectation of almost ev’ry thinking man,” New Hampshire failed to ratify. Fearing defeat, the federalists moved to adjourn without a vote and set a new date for the convention on June 3; the motion to do this squeaked by with only a five-vote margin.

It is hard to tell what exactly happened. The proceedings were not well recorded or reported. The stated objections included compromises regarding slavery and the failure to impose a religious test on federal office holders.

Langdon blamed a handful of “designing men” who had managed to frighten “the people almost out of what little senses they had.” Among “a thousand other absurdities,” these troublemakers stated that the Constitution put “the liberties of the people” in danger and spread fake news that the Massachusetts convention, which had already adjourned, was set to vote down the ratification.

Although Langdon tried to spin the forced adjournment as a victory, Washington was crushed. His response to Langdon’s report—in a letter currently on display in the Huntington Library’s Main Exhibition Hall—reveals the depth of his despair. The letter is part of The Huntington’s L. Dennis Shapiro Collection.

Washington found the “conduct of New Hampshire” utterly “incomprehensible.” The Constitution, after all, promised “energy & security” to the entire nation and held out special “advantages to the smaller States.”

Washington agreed that the adjournment of the New Hampshire convention was “certainly prudent.” However, he feared that events in the state would embolden the “anti-federal characters” to put forth “unjust & uncandid representations” and “influence the minds of the people & prejudice them” against the Constitution.

Washington was right to worry. The New Hampshire debacle not only caused the value of federal securities to collapse, but also complicated the already combative ratifying contests in key states, including Washington’s native Virginia. If Virginia failed to ratify, Washington would have been ineligible for the presidency.

In the end, it took a sustained political campaign—complete with the usual array of underhanded tactics, partisan vitriol, and even occasional violence—to create the United States of America.

On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire finally became the ninth state to ratify, fulfilling the quota. It was not the resounding victory that Washington had hoped for. The final vote was 57-47, contingent on “alterations & provisions” to the Constitution. Virginia followed four days later, with similar conditions and by the equally thin majority of 89-79.

On March 4, 1789, when the first session of the U.S. Congress assembled in New York, the congressmen were greeted by an artillery salute honoring each ratifying state. There were only 11 shots. It would take seven more months for North Carolina and more than a year for Rhode Island to adopt the Constitution.

Three years later, Edmund Jennings Randolph, who in 1787 had famously refused to sign the Constitution, wrote to Washington, admitting that “the constitution would never have been adopted, but from a knowledge that you had once sanctified it.”

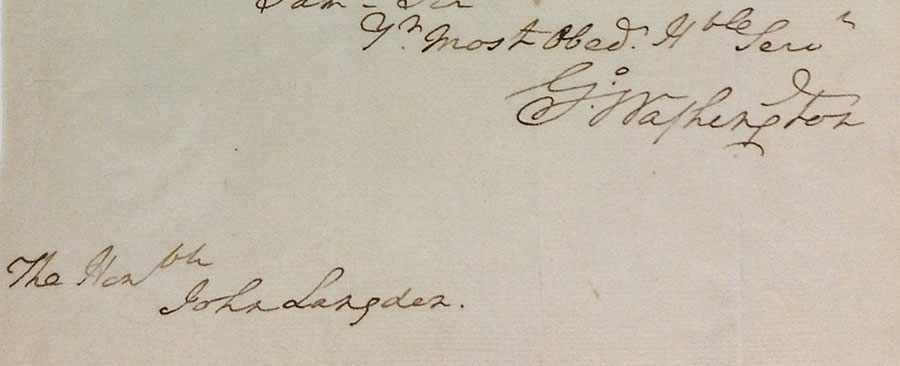

George Washington (1732–1799), detail of autograph letter, signed, to John Langdon (1741–1819), April 2, 1788. The Shapiro Collection. Promised gift of L. Dennis and Susan R. Shapiro. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.