The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Interview with Octavia E. Butler Fellow Alyssa Collins

Posted on Wed., Feb. 2, 2022 by

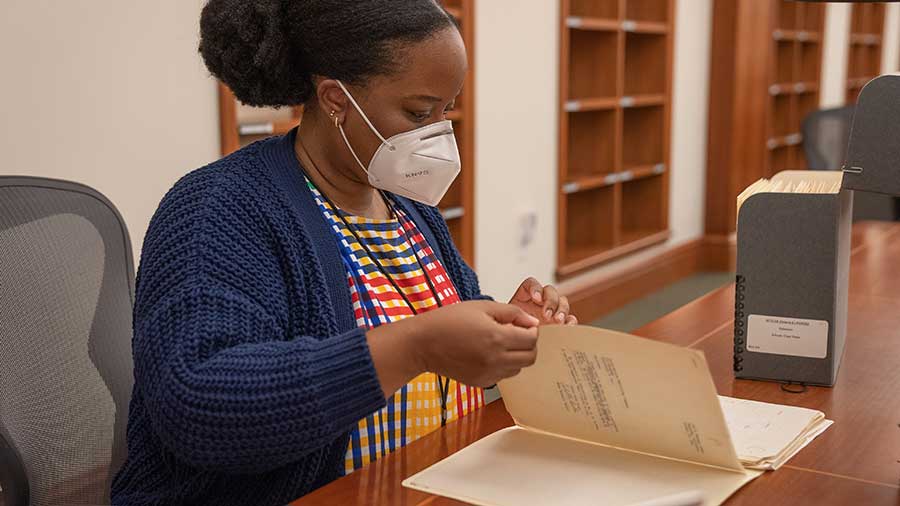

Alyssa Collins, The Huntington’s first Octavia E. Butler Fellow. Photo by Shane Lin.

Alyssa Collins, assistant professor of English language and literature and African American studies at the University of South Carolina, is The Huntington’s first Octavia E. Butler Fellow for the study of the renowned science fiction writer. Butler (1947–2006) was the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur “genius grant” and the first African American woman to win widespread recognition writing in that genre. The Huntington holds Butler’s archive.

The Huntington’s research grant provides support for a scholar to spend a full academic year working with Butler’s literary archive, which, over the past seven years, has become the most frequently requested collection at The Huntington.

I recently sat down to talk with Alyssa Collins about how she became interested in Butler, what led her to The Huntington, and her experience so far as a research fellow.

When did you become interested in science fiction or speculative fiction?

I think I’ve always been interested in science fiction and the speculative. When I was a child, I read anything I could get my hands on, but what I wrote was a different story. Recently my parents dug up some of my old stories. They’re written on those little bound books that teachers would have you write stories in for class. I even created a publishing imprint for them. While I was not as purposeful and diligent a writer as Butler was as a child, all my works were science fiction. I was apparently very into time and dimensional travel.

How did you first encounter the work of Octavia Butler? What intrigued you most about her work?

I first encountered Butler in a graduate course on feminist literature and theory. We read Parable of the Sower, an apocalyptic novel published in 1993 and set in near-future America. I was really intrigued by the prescient nature of the novel, but I immediately wanted to know if she had anything weirder on her backlist. I managed to get my hands on her award-winning 1984 short story “Bloodchild,” a tale about aliens and male pregnancy, and was not disappointed. After that, I was pretty much hooked.

Alyssa Collins looking at Octavia E. Butler materials in The Huntington’s Ahmanson Reading Room. Photo by Aric Allen.

I understand that this is not your first time at The Huntington. What brought you here initially? And what did you realize during that visit that made you want to return?

I first came to The Huntington during my graduate studies. I was writing my dissertation about representations of the human and posthuman by Black authors in the 20th century. I was interested in determining links between contemporary scientific thought about author’s representations. I wanted to know what, if anything, Butler knew about genetics, DNA, and biotechnological narratives of her day. So, I came for a couple of weeks and found that she indeed knew a lot about all of it—and a lot more. What really excited me was the extent of Butler’s research and the care she took in doing it. Her research notes and marginalia are both incredibly detailed and intensely organized. I quickly realized that the conversation in which she was participating with her novels was so much bigger than I had previously expected. Coming to the archive that first time really impressed upon me the reality of Butler being not only a fantastic writer, but also an extraordinary archivist and theorist.

Now that you are taking a deep dive into the Butler archive, what kinds of material are you investigating and why?

This time at the archive, I’ve had more time to follow up on several hunches and questions that I’ve had in the intervening years. My book project, born out of that first project, uses Butler’s thinking and writing on the human and the posthuman as an anchor to reveal the ways that Black women writers are imagining humanity. This is a speculative investigation of humanity that is not always on the scale of bodies, but instead on the scale of cells. My argument springs from Butler’s engagement with and theorizing of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cancer cells were harvested without consent in 1951 for medical research, and the story of the immortal cell line that has been maintained from a sample of her cells. It’s clear that Butler’s interest in cells and cellular replication developed across her works. I’ve been looking at large swaths of Butler’s science research files, her notes, and the bibliographies she compiled during drafting.

What insights are you having? Any surprises?

Butler continues to surprise me with the breadth of her interests and depth of her knowledge. I often wonder if she knew about a certain scientific theory or scientist, and later I will find concrete evidence in a note, or in the margin, that she did in fact know and had strong feelings about it. I don’t think you ever really expect to enter someone’s archive and have them continually surprise you, especially with all the research we do as scholars. However, I can say that even though I started out knowing Butler as an incredible writer and scholar, every day I spend in her archive only increases my esteem for her.

Alyssa Collins reads a typewritten page from the Octavia E. Butler papers, the most frequently consulted collection in the Library. Photo by Aric Allen.

Kevin Durkin is the editor of Verso and the managing editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.