The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Behind the Scenes with Sonya Levien

Posted on Wed., March 9, 2022 by

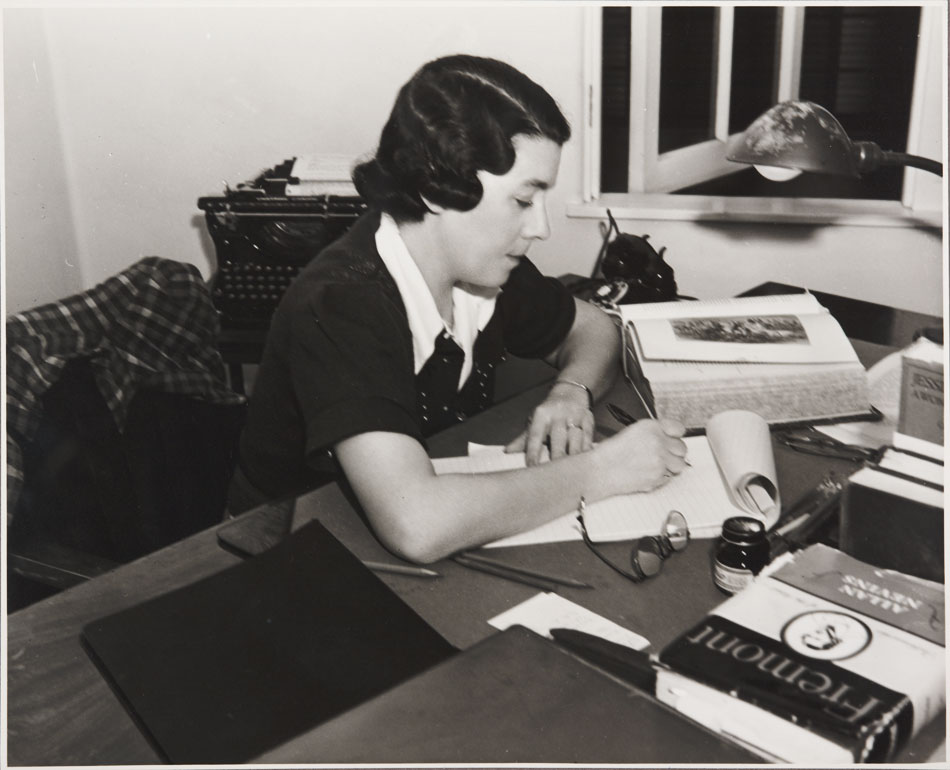

Portrait of Sonya Levien, undated. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The life of Sonya Levien (1888–1960) reads like a rags-to-riches fairy tale. But it is also a story of fortitude, feminism, and the ability to balance personal, family, and financial ambitions. The Huntington holds the papers of Levien, who started out as a Russian Jewish immigrant to the United States and became a factory worker and young radical; a suffragist, lawyer, editor, and author; and, eventually, an Oscar-winning screenwriter with 80 film credits to her name.

New York University law school class photo with Sonya Levien (second row, fourth from right), ca. 1908. Levien was among the first women to graduate from NYU Law and, after being admitted to the New York bar, was one of fewer than 600 female lawyers in the entire United States. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Born Sara Opeskin in Panimunik, in Imperial Russia, an area that is now Lithuania, Sonya was the eldest of three children. Her father, Julius, was sentenced to hard labor in Siberia for his political affiliations when she was 2. He later escaped to America and earned enough money to send for his wife and children to join him when Sonya was 8. Julius changed his family’s name to Levien, taking the name of the German engineer who helped him emigrate.

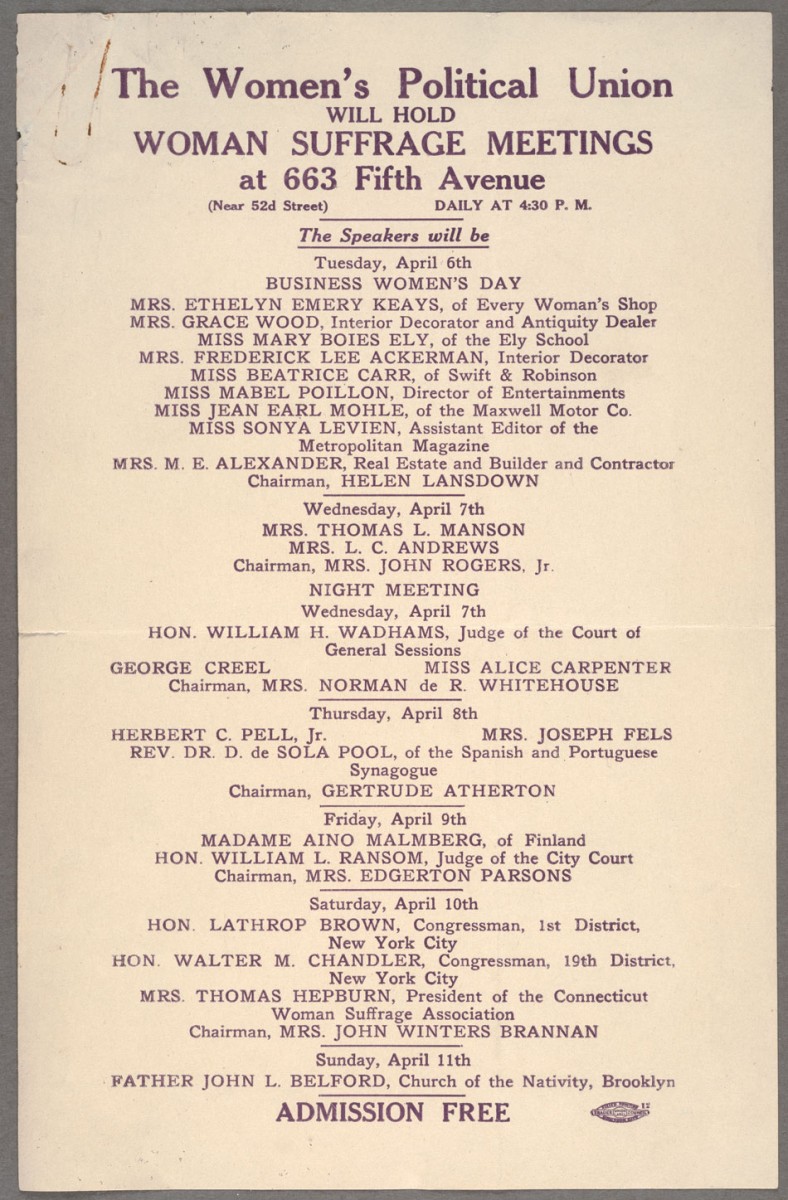

Women’s Political Union flyer, 1915. Levien was one of the featured speakers on the businesswomen’s day of a “woman suffrage meeting,” hosted by the Women’s Political Union, April 6, 1915. Women achieved the right to vote in the United States in 1919. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Levien family settled in the tenements of New York City. Sonya worked in a feather duster factory as a teen and was drawn to labor-friendly socialist groups. She borrowed money to take a stenography course in the hope of becoming a secretary. She was ultimately hired by her mentor, Rose Pastor Stokes. Stokes was another Russian Jewish immigrant, an activist and early promoter of women’s rights, and the wife of millionaire J.G. Phelps Stokes.

Cover of Metropolitan, September 1917. Levien was hired as an editor by Carl Hovey, co-editor of Metropolitan magazine, a liberal literary monthly. Hovey and Levien married in 1917. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Levien attended law school at New York University and passed the New York bar examination. But she was also a talented writer and began selling some of her first work while she was still a student. She quickly turned from a career in law to writing and editing as an avenue for her social efforts. She worked at a few different publications before she was hired as an editor by Carl Hovey, co-editor of Metropolitan magazine, a liberal literary monthly. Hovey was well-to-do, white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. He and Levien married in 1917.

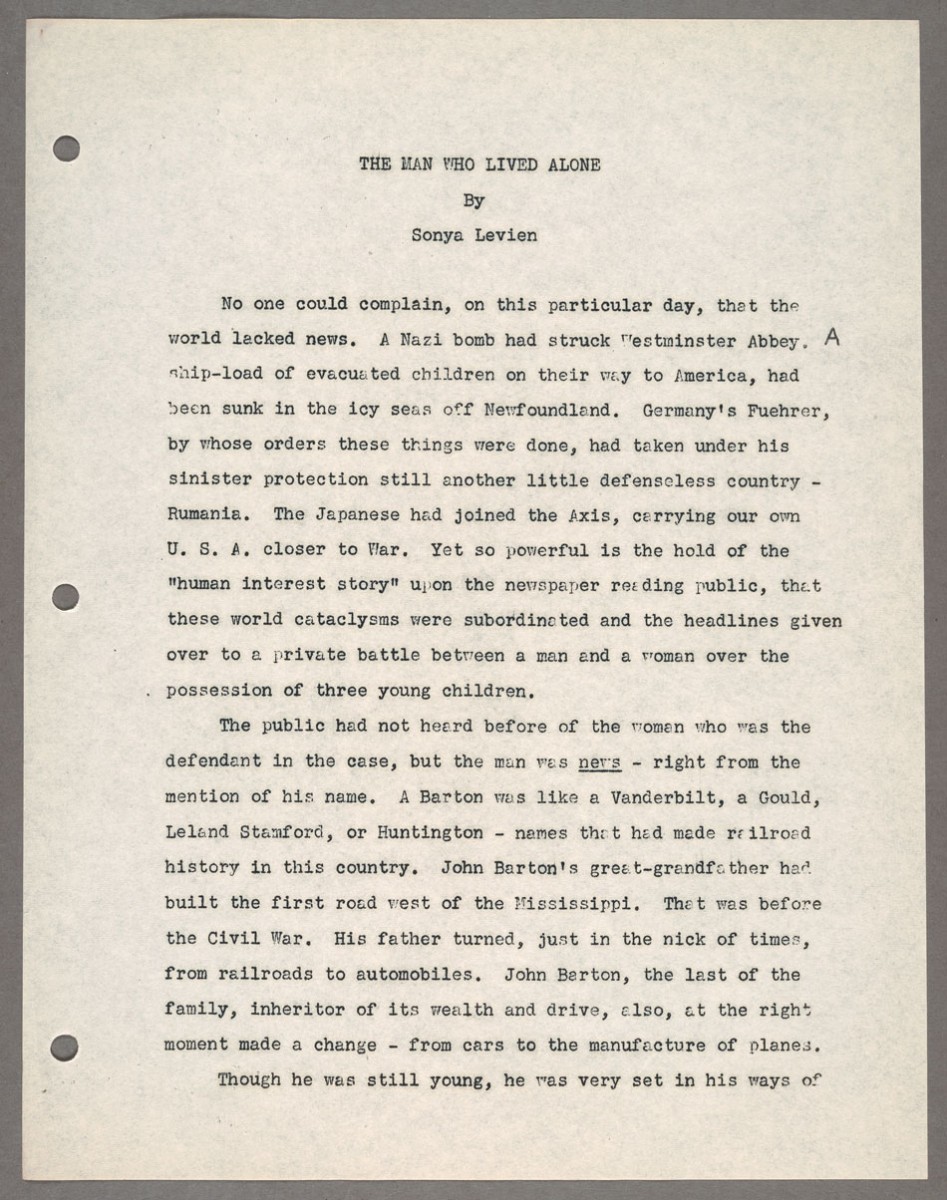

First page of a draft of The Man Who Lived Alone, a novella by Levien. The rights to this romantic comedy about a woman reporter were acquired by Universal in 1941; it was never produced for the screen, and the novella itself was never published. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

At the Metropolitan, Levien edited the work of former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who was a regular contributor. He affectionately called her “little miss anarchist,” Levien later wrote, “for no other reason that I could discover except that he knew I was born in Russia and had been reared in a nihilistic group.” Levien did write passionate editorials on progressive subjects, including women’s suffrage, and incorporated social issues into her fiction.

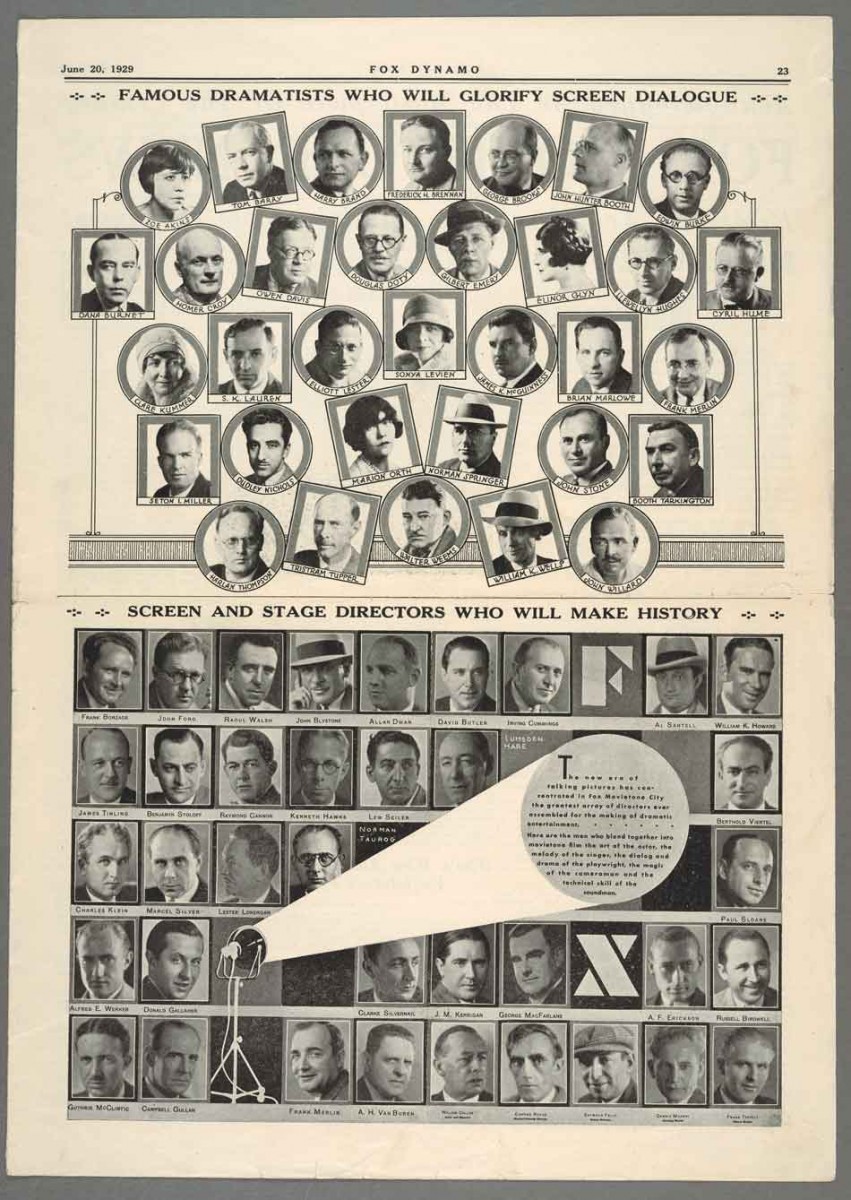

Promotional advertisement in the trade magazine 20th Century-Fox Dynamo, 1929. Located at the very center of a dazzling array of writers, from Booth Tarkington (two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Magnificent Ambersons) to Zoe Akins (Pulitzer Prize–winning dramatist of The Old Maid), Sonya Levien was one of five women among 28 men. Hired by Fox in 1929, Levien would work for the studio for 10 years, becoming one of its top and best-paid screenwriters. (The Huntington also holds the papers of Akins.) The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Levien sold her first story to Hollywood in 1918, receiving her first screen credit in 1919. In 1922, she accepted a job as a scenario writer of silent films with Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, a motion picture and distribution company, at the considerable salary of $24,000 a year with annual increases of $5,000 over the next five years. The young wife and mother moved from New York City to Los Angeles, but after a year, she missed her family and her little boy, quit, and moved back home.

The lure of Hollywood still called, however, and in 1925, Levien and Hovey moved their family to California. When Hovey could not find steady work in the movie industry, Levien became the primary breadwinner for their family and would remain so for the rest of their lives.

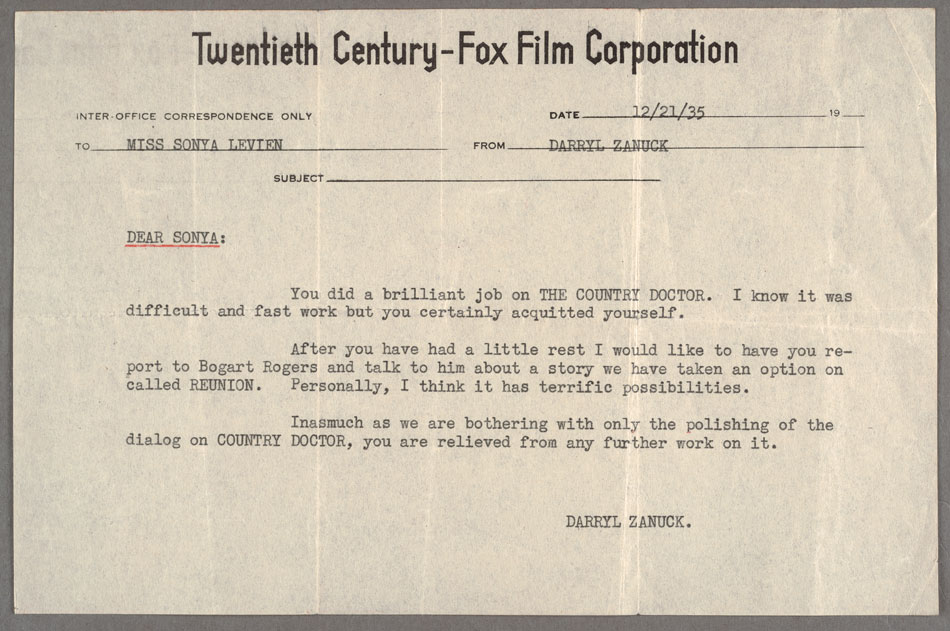

Telegram from producer Darryl Zanuck of Twentieth Century-Fox, congratulating Sonya Levien on the script for The Country Doctor, Dec. 21, 1935. Released in 1936, The Country Doctor starred Jean Hersholt, June Lang, and the Dionne quintuplets in a story loosely based on the birth of the world’s first-known surviving quintuplets. A New York Times reviewer called it “an irresistibly appealing blend of sentiment and comedy.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Despite her youthful political activities, Levien seems to have given them all up to work in the unforgiving studio system. If she maintained strong political opinions, she kept them to herself, even neglecting to comment when her daughter and son-in-law, also writers in the industry, were blacklisted for communist affiliations. Her friends ranged from U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins to pianist Oscar Levant. She was known for her salons and parties, many hosted at her Malibu beach house. Later, she rented the Hollywood mansion of former silent-film cowboy star Tom Mix.

From left: Ira Gershwin, Sonya Levien, Guy Bolton, and George Gershwin, ca. 1930. Levien and Bolton wrote the script for Delicious, which was largely a vehicle for a miscellany of Gershwin music. The film did not do very well, but Levien’s friendship with the Gershwin brothers did. Levien later wrote a treatment for the 1945 fictionalized biopic of George Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Over the next three and a half decades, Levien wrote for nearly every major studio: Universal, Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount), RKO, Warner Brothers, Columbia, Twentieth Century-Fox, and MGM. She worked with such Hollywood notables as Will Rogers and George Gershwin.

Photograph of Sonya Levien working at her desk, ca. 1933. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

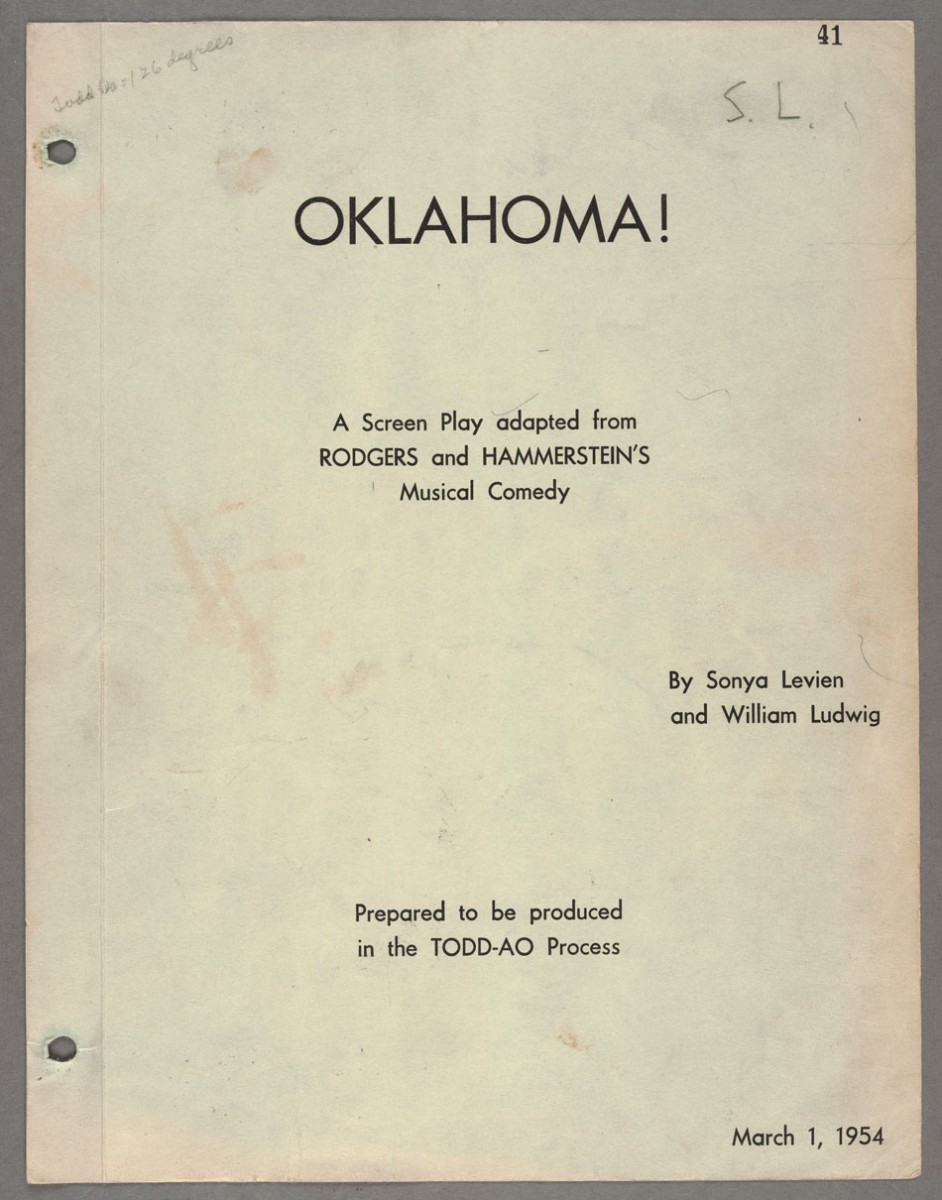

She was known as a quick, versatile, and tireless writer—with a special talent for adaptations. She worked with Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein on the film adaptation of the musical Oklahoma! as well as on adaptations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped and Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. She and co-writer William Ludwig won the Academy Award for best screenplay for the 1955 biopic Interrupted Melody.

Sonya Levien and William Ludwig, draft of screen adaptation of Oklahoma!, March 1, 1954. Levien and Ludwig worked on several screenplays together toward the end of Levien’s career, including The Great Caruso (1951), the popular Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma! (1955), and the film that won them an Oscar, Interrupted Melody (1955).

Levien was one of the most successful screenwriters of her era, with a career that extended from 1919 to her death in 1960—an extraordinary legacy for a woman in a film industry long dominated by men.

Natalie Russell is the assistant curator of literary collections at The Huntington.