The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Charles Yu in Conversation

Posted on Tue., March 15, 2022 by

Founders’ Day is observed annually at The Huntington in honor of Henry and Arabella Huntington’s roles in envisioning and establishing the institution.

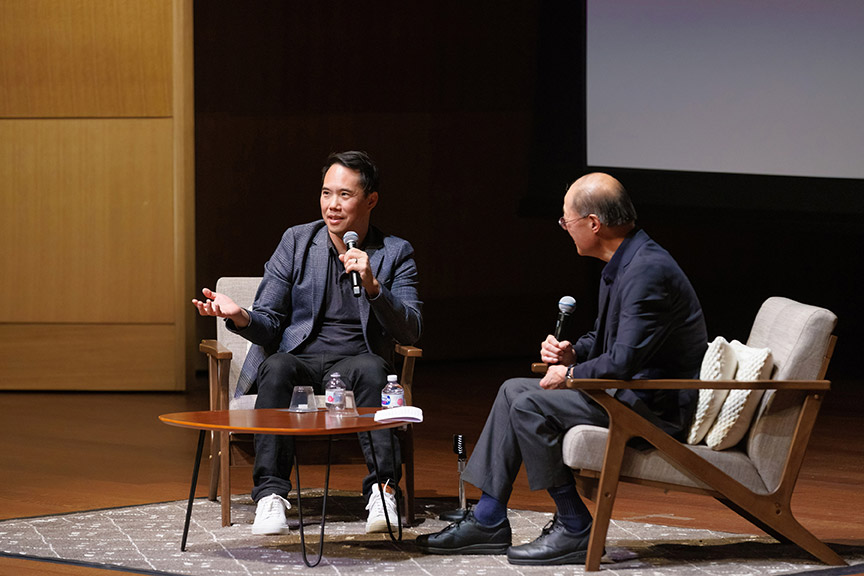

Huntington President Karen R. Lawrence (right) welcomed acclaimed writer Charles Yu (left) and Huntington Trustee Simon K.C. Li to the Founders’ Day event at Rothenberg Hall on March 2. Photo by Sarah M. Golonka.

This year’s Founders’ Day program reflected intersecting areas of strength at The Huntington. Since the institution’s founding, literature has been a pillar of the humanities collections, with recent literary guests including Susan Orlean, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Marilynne Robinson. The Huntington’s collections also include extensive materials related to the history of Los Angeles’ Chinatown and Chinese immigration in Southern California. Most recently, The Huntington collaborated with the Library Foundation of LA and LA Public Library on “Archive Alive: Stories and Voices from L.A. Chinatown,” an online and off-site exhibition.

For The Huntington’s 2022 Founders’ Day celebration, acclaimed writer Charles Yu joined Huntington Trustee Simon K.C. Li in conversation before a live audience. Yu won the National Book Award for his most recent book, Interior Chinatown, which he’s now adapting into a series for Hulu. He and Li discussed Yu’s experiences writing in multiple genres, the role of fiction in constructing identity, and the current dialogue about identity and race in America.

Open to experimenting with format—his short story “Problems for Self Study” was written using algebraic equations—Yu wrote Interior Chinatown as a screenplay.

The book follows the life of Willis Wu, an actor who strives to rise above playing bit parts, such as Generic Asian Man on a cop television series. His dream is to be cast as Kung Fu Guy, which, as he sees it, is the ultimate role for an Asian male actor.

The screenplay format helped illustrate how Asian actors are often trapped in a narrative, since they have been historically restricted to stereotypical roles, such as people working in a restaurant or performing martial arts.

Yu had been working in television for a few years—most prominently on the HBO series Westworld—when the idea hit him for the structure of the book. “What I really needed was a way for the reader to be able to jump with me back and forth in and out of the script. I needed to tell the story on two levels and give a very clear visual and conceptual marker of here’s where the official story is. And here’s Willis at the margin being invisible and then suddenly visible. The format really broke something open for me.”

In the book, Yu writes, “Chinatown and indeed being Chinese is and always has been, from the very beginning, a construction, a performance of features, gestures, culture, and exoticism. An invention, a reinvention, a stylization. Figuring out the show, finding our place in it, which was the background, as scenery, as nonspeaking players. Figuring out what you’re allowed to say. Above all, trying to never, ever offend. To watch the mainstream, find out what kind of fiction they are telling themselves, find a bit part in it. Be appealing and acceptable, be what they want to see.”

Li pointed out that Willis represents Asians’ invisibility in mainstream media. “It’s pretty self-evident that over the years, decades, Asian Americans have not been well represented by Hollywood. Somebody asked me recently, ‘Why does that matter? What does it do to help you to have representation in common culture?’”

Yu responded that he grew up watching TV—favorite shows included Three’s Company, Growing Pains, and Diff’rent Strokes—and the shows he watched lacked Asian American representation.

Yu and Li share a laugh at the Founders’ Day event at Rothenberg Hall on March 2. Photo by Sarah M. Golonka.

“I saw a distorted picture of America that had a very specific kind of filter, which was, there are no Asians in America,” Yu said. “In this window into that version of the United States, that version of America, which in a lot of cases is aspirational, there are groups excised from . . . the story.”

To demonstrate the effects of this exclusion, Yu asked, “When I say ‘American,’ is the first face that pops into your head a face like this?” He pointed to himself, and then said: “I think that’s why it matters.”

Yu’s definition of success, as a viewer, is to see people of all different shapes, sizes, and colors on TV. He noted that he can already see some progress when his children watch TV and don’t stop what they’re doing to say, “Oh, look, an Asian on TV.”

He added, “For me, the goal is that it’s not remarkable anymore.”

During the event, Yu and Li discussed why it’s important to have Asian American representation in Hollywood. Photo by Sarah M. Golonka.

Cheryl Cheng is the senior editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.