The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Lily Lee Chen, Mayor of Monterey Park

Posted on Tue., March 22, 2022 by

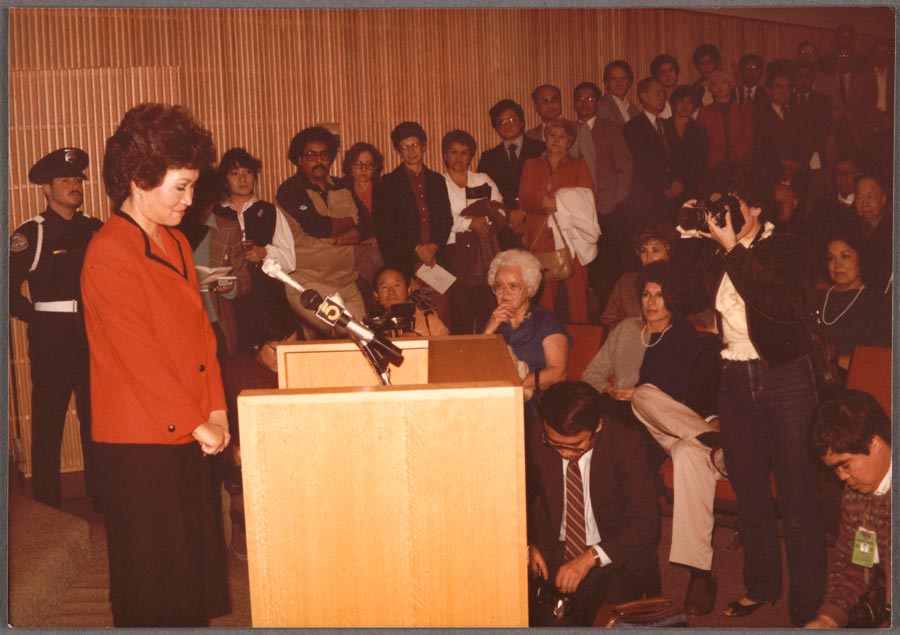

In 1984, Lily Lee Chen became the first female Chinese American mayor in the nation. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

On April 13, 1982, Lily Lee Chen was elected to the city council of Monterey Park, a city in the western San Gabriel Valley region of Los Angeles County that had become one of the first “suburban Chinatowns” in the United States. In 1984, Chen made history by becoming the first female Chinese American mayor in the nation.

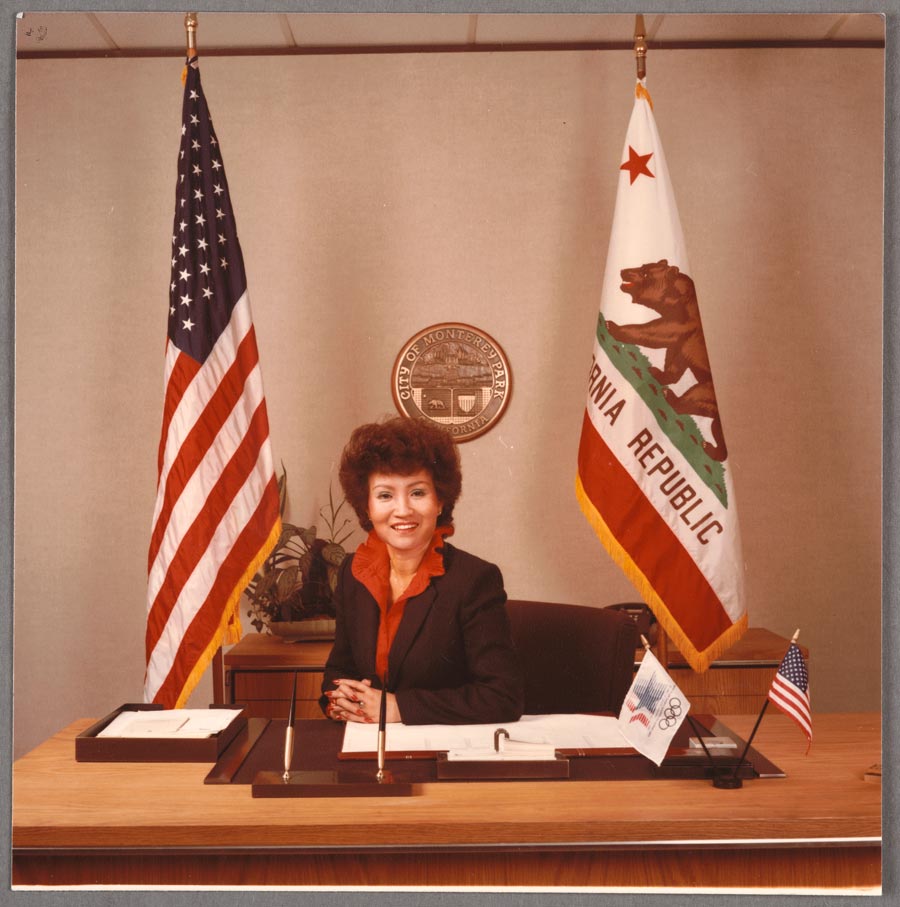

Lily Lee Chen’s official portrait as mayor of Monterey Park, California, 1983. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Although the position of mayor was largely ceremonial in Monterey Park and limited to a 9 1/2-month term, Chen was one of only five city council members who governed the city of roughly 60,000 residents during a period of demographic change and rising racial and ethnic tensions, exemplified by a proposed English-only movement. Today, the Lily Lee Chen papers, which were recently acquired by The Huntington, preserve this turbulent time in Southern California history.

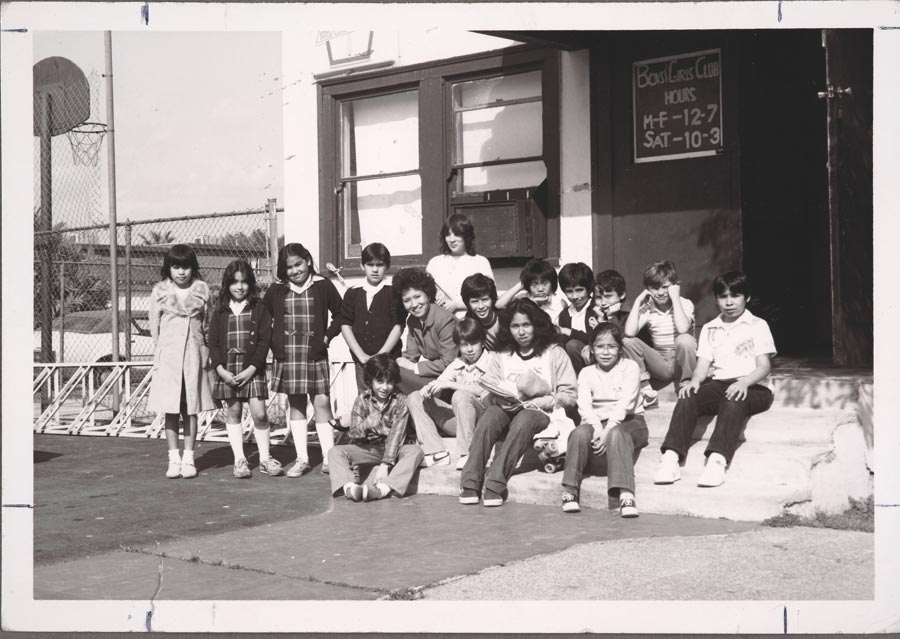

Lily Lee Chen at a Boys and Girls Club in Monterey Park, California, 1980s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

When the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law, legal discrimination against Asian immigrants was officially abolished. During the next two decades, Monterey Park changed from being a predominantly white middle-class community (85% white in 1960) into a bustling international hub that attracted immigrants and real estate developers primarily from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. In 1986, the city’s population was 22% white, 37% Latino/a, and 40% Asian.

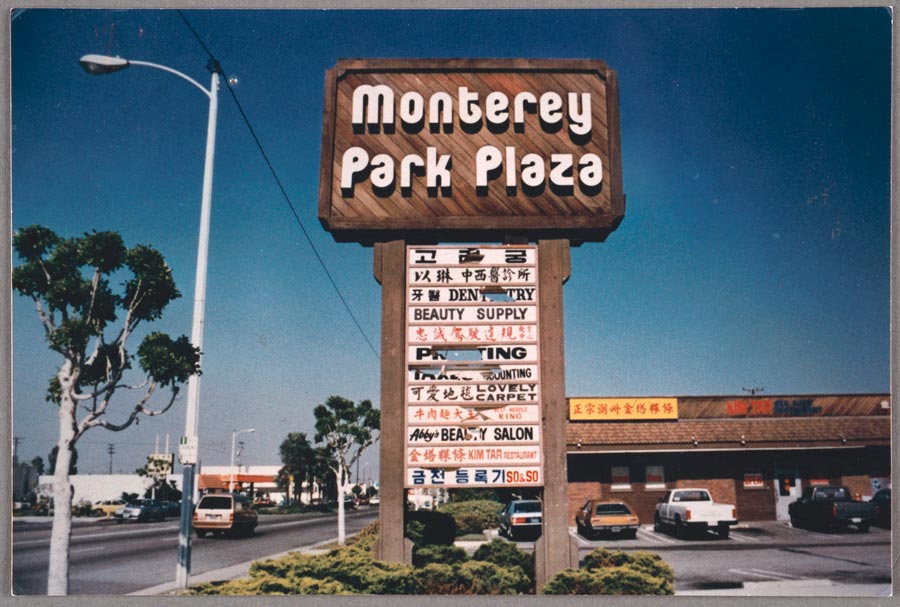

Business signs in Monterey Park, California, 1980s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

With more than 20 years of experience working in leadership roles for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services, Chen devoted herself to her city council position. She helped to close a local landfill and secured funds to expand an elementary school. As mayor, she successfully lobbied for Monterey Park to host the field hockey competition during the 1984 Summer Olympics. Chen also helped the city win the National Civic League’s All-America City Award in 1985, a recognition of Monterey Park’s multiculturalism and prosperity. Her supporters often cited her tireless drive to get things done. Democratic Party leaders regarded Chen as a rising star.

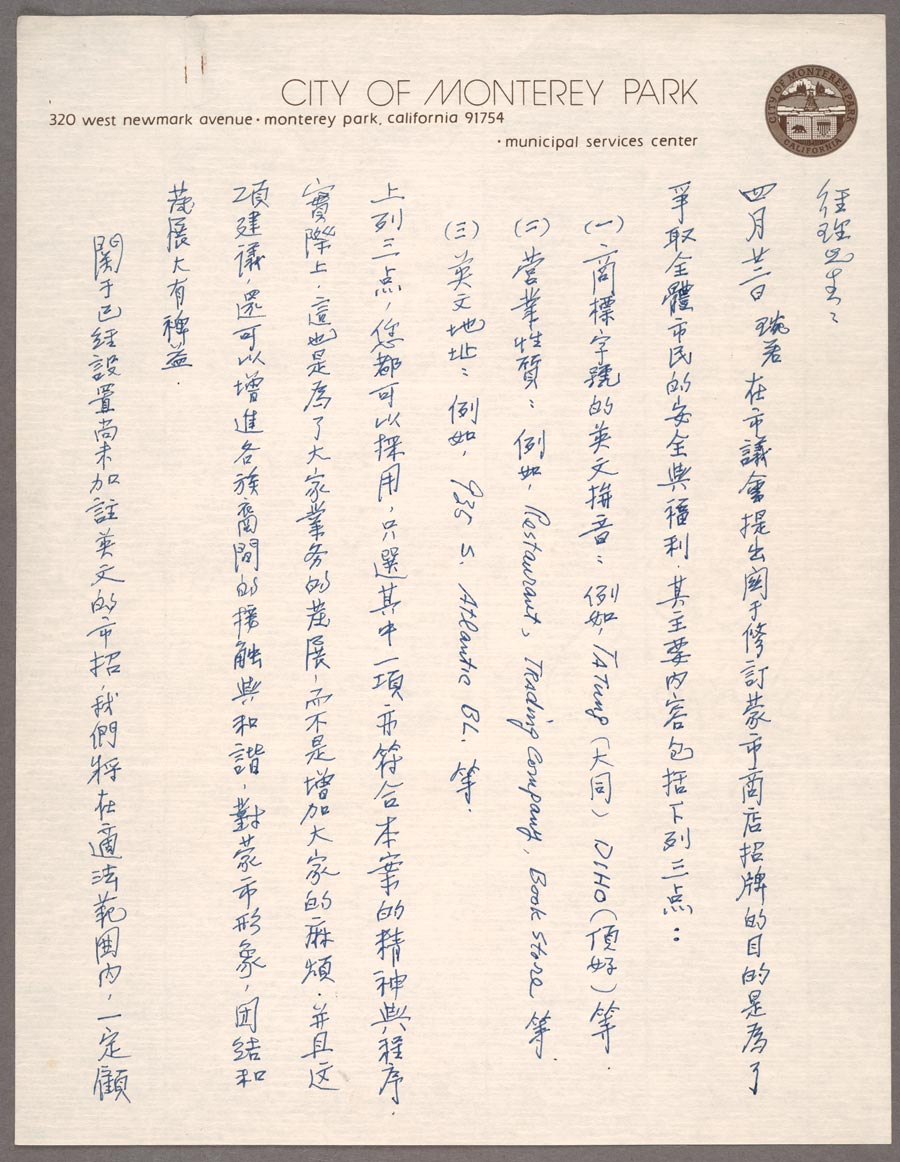

Draft of a letter by Lily Lee Chen to Chinese businesses, 1985. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Despite Chen’s political success and the city’s unprecedented economic growth due largely to the enterprise of immigrants, Monterey Park became swept up in language politics and xenophobia. The influx of immigrants from Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and elsewhere to Monterey Park resulted in an increase of immigrant-owned businesses. Many shop owners chose to advertise in Chinese to attract customers.

Campaign letter by Lily Lee Chen, 1986. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Starting in the early 1980s, debates erupted because some Monterey Park residents wanted a strong, English-only sign ordinance. Chen tried to defuse the situation by working out a compromise, adopting a rule that required at least 50% English on all business signs in the city. But Chen’s compromise did little to appease her critics. Monterey Park’s English-only movement never made it to the municipal ballot, but it did inspire future movements that sought to restrict the use of languages other than English, such as Monterey Park’s Resolution 9004 and California Proposition 63 in 1986. That same year, Chen and her two Latino city council colleagues, David R. Almada and Rudy Peralta, were voted out and replaced by candidates who supported the English-only movement.

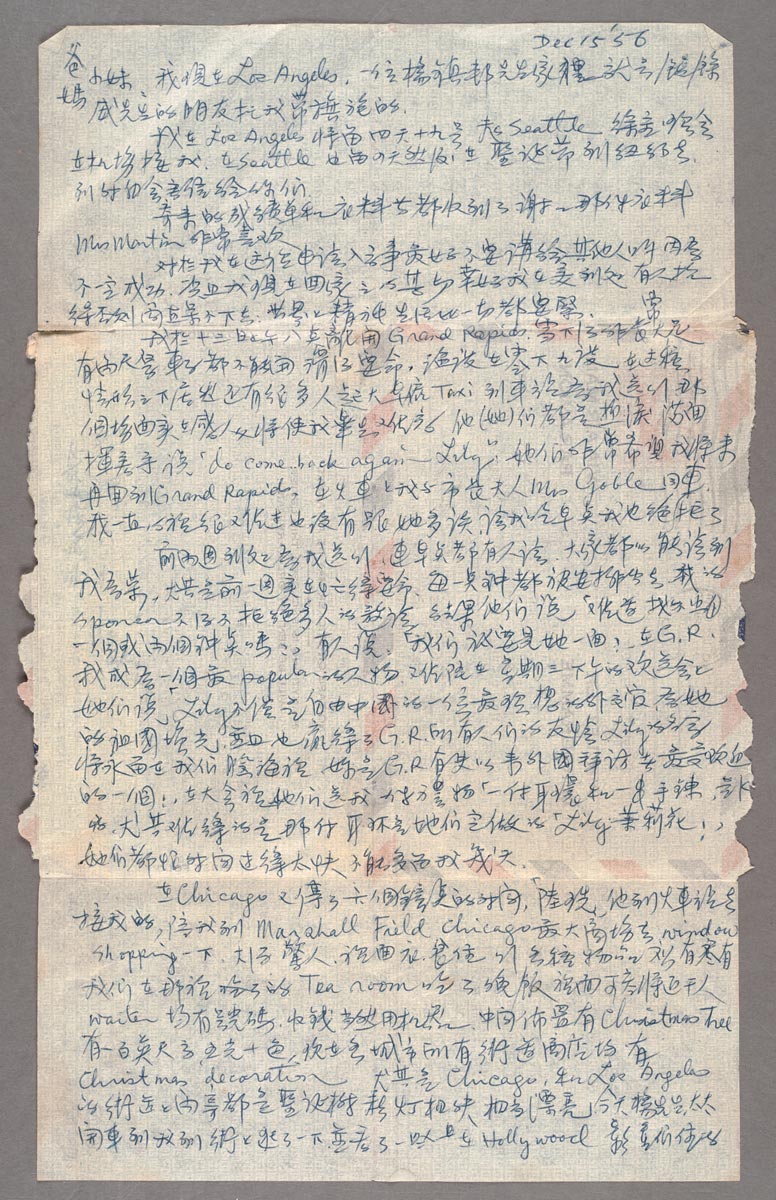

Letter by Lily Lee Chen addressed to her mother, father, and sister, 1956. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Lily Lee Chen papers contain materials related to her political career, including campaign flyers, newspaper clippings, handwritten letters from her constituents and supporters, and political attack ephemera. The collection also includes documents related to Chen’s early experience as an immigrant from Tianjin, China, and from Taiwan. These include letters she wrote to her parents, family photos that date to the early 20th century, materials from her 27-year career at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services, and items stemming from her efforts to secure women’s rights and minority rights in the United States. When the collection is cataloged and processed, it will be made available to researchers interested in this period of Southern California history.

Li Wei Yang is the curator of Pacific Rim collections at The Huntington.