The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Early Modern Ireland and the Wider World

Posted on Tue., April 5, 2022 by

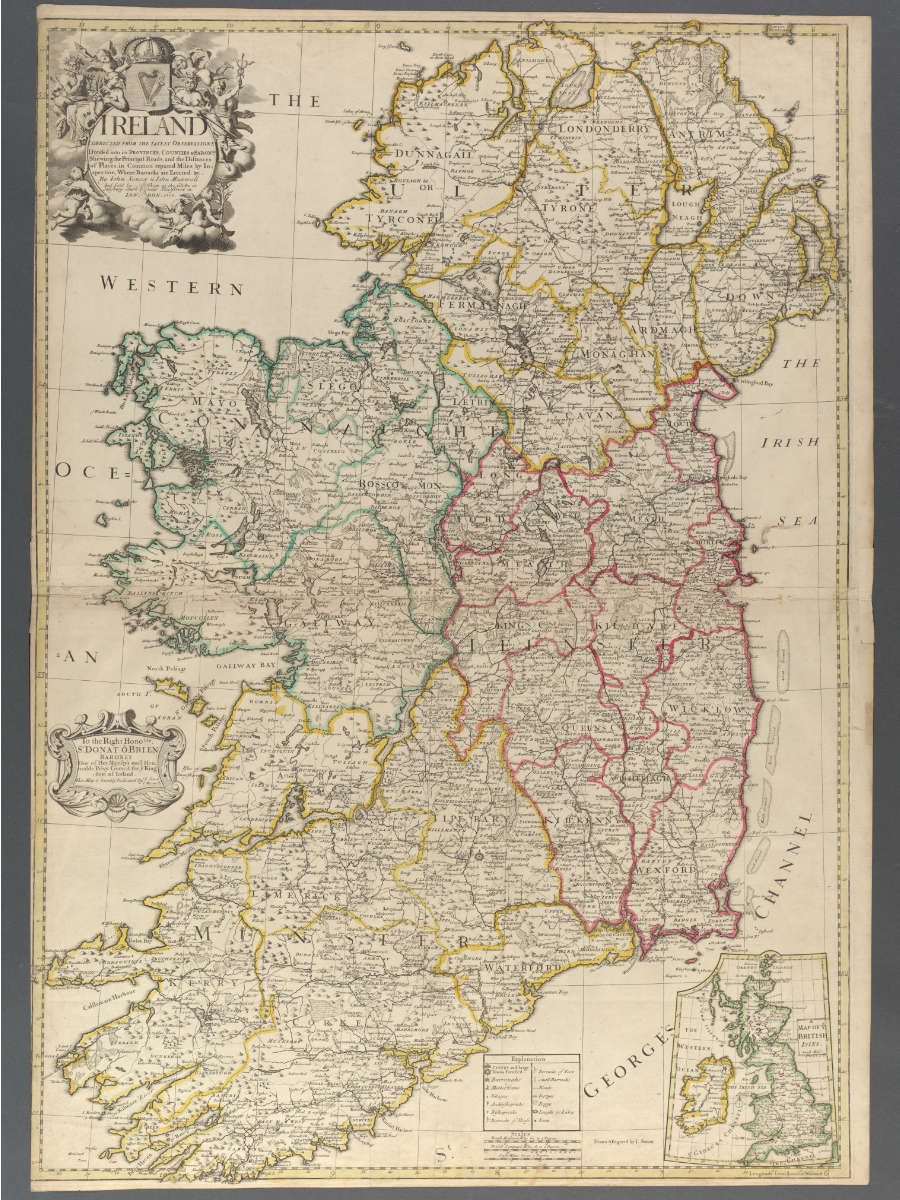

Ireland: corrected from the latest observations divided into its provinces, counties & baronies shewing the principal roads and the distances of places, in common reputed miles, by inspection, where barracks are erected &c / by John Senex & John Maxwell and sold by them at the Globe in Salisbury-Court near Fleetstreet in London, London, 1712. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Sun-drenched Southern California is hardly the first place that comes to mind when one thinks of Ireland and its history. And yet, The Huntington is one of the largest repositories in the world for Irish-related manuscripts and almost certainly the largest single archive for Irish history in North America.

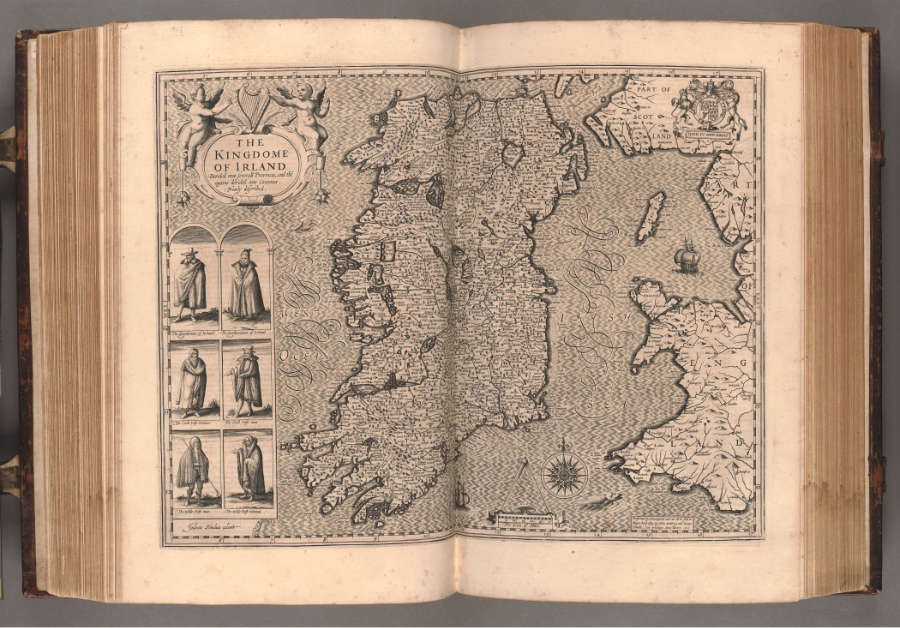

On April 8 and 9, the “Early Modern Ireland and the Wider World” conference will, for the first time, bring to light the extensive manuscript collections at The Huntington for the historian of 16th-, 17th-, and 18th-century Ireland. Drawing on the world-class collections, speakers will address themes at once familiar to early modern Ireland—violence, colonialism, religion—while also asking new questions that provide fresh directions for research. How did nascent environmental controls influence English state building in Ireland? What led scores of Irishmen to join the East India Company and become key stakeholders in the British imperial project? And why did a bunch of Catholic Irish mercenaries wind up governing English Tangier in North Africa during the 1660s and 1670s?

The answer to these and countless other new questions can be found in the manuscripts of nearly every major early modern British collection at The Huntington, including the Hastings, Ellesmere, Stowe, and Blathwayt collections.

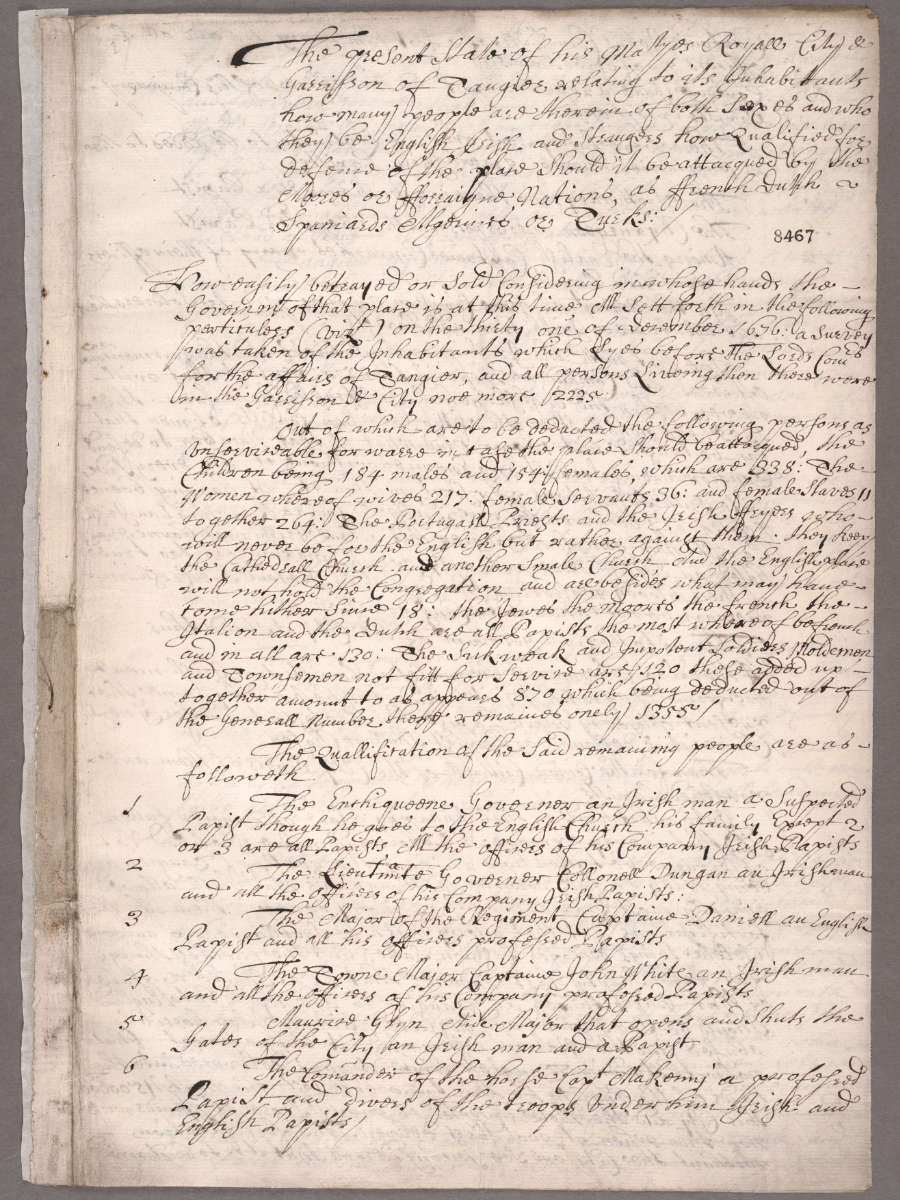

Survey of “English, Irish and Strangers” at Tangier, 1679. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Hastings Collection, the crown jewel of The Huntington’s Irish archive, includes more than 2,000 individual items covering almost 170 years of Irish history, from 1583 to 1751. The comprehensive nature of the Hastings Collection allows historians to reconstruct—often in minute detail—key political, social, and economic events. Elizabethan customs records, Jacobean warrants, Caroline religious decrees, Cromwellian depositions, and Restoration inquisitions bring to life the early modern era. Of obvious significance are the thousands of items detailing the transfer—and seizure—of land from native Irish to Old English and, ultimately, New English throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Ellesmere Collection sheds light on Irish politics, religion, education, land, law, and parliamentary affairs from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I to that of King George I, almost always in a “British”—that is to say, English, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh—context. The Stowe Collection and its subcollections of the Brydges, Grenville, Nugent, and Temple papers contain hundreds of items that reveal the later Stuarts’ and early Hanoverians’ continued preoccupation with Ireland. In the middle of the Popish Plot, for instance, when Jesuits were believed to be planning the assassination of King Charles II to set his Catholic brother on the throne, English authorities viciously debated the virtues of Catholic commissioners of the peace in Ireland. They also fretted over William O’Brien, second earl of Inchiquin, an “Irish man, and suspected papist,” governing a corrupt, debauched garrison in Tangier.

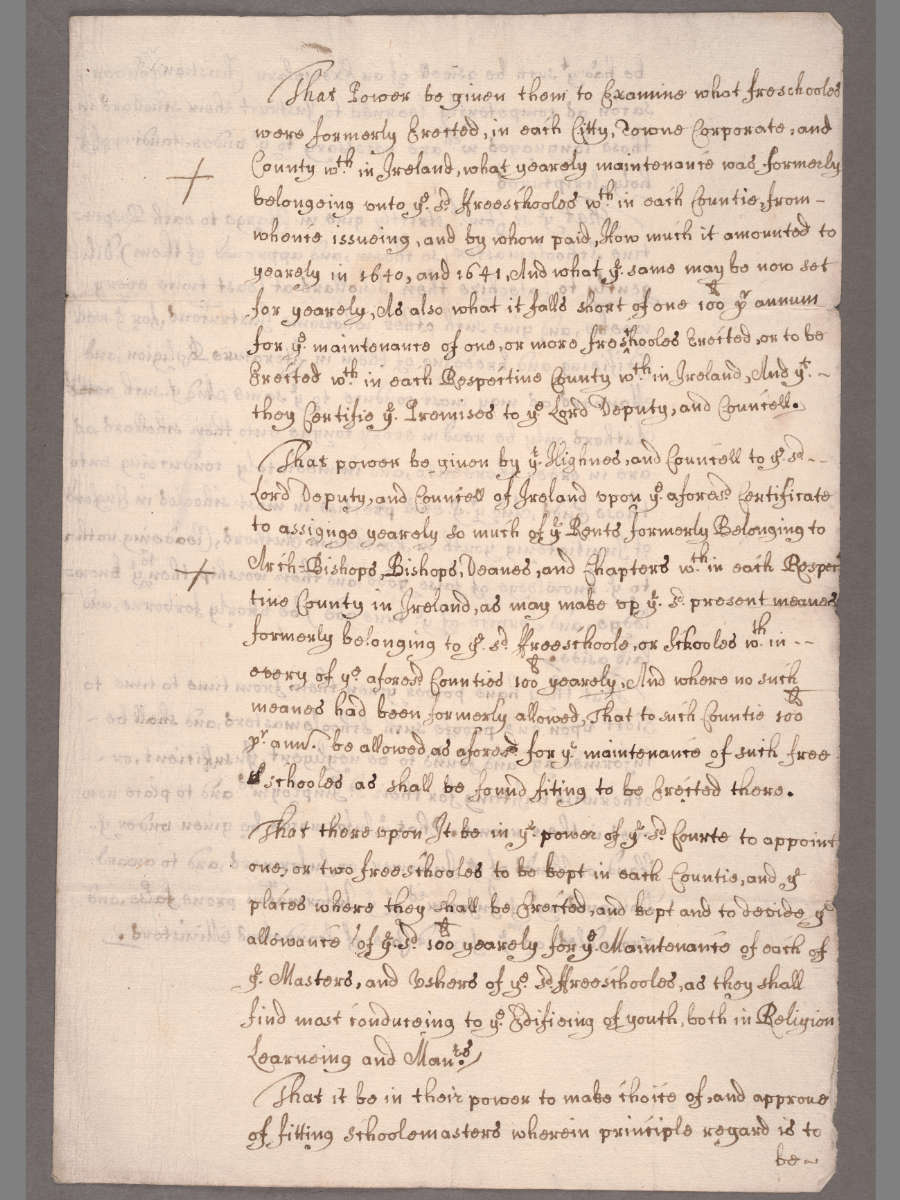

A Proposal Concerning Free Schools and Schoolmasters in Ireland, 1655. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The threat posed by the Catholic Irish became most acute in Tangier and dozens of other settlements in the expanding English world. The Blathwayt papers highlight the role of the Irish in the Americas, from the West Indies to New England, in the 17th and 18th centuries. Here, recalcitrant Irish Catholics colluded with African, American Indian, and Scottish laborers to challenge English authority and governance. Officials routinely resorted to familiar methods of coercion and punishment, most of which they had honed in Ireland in earlier decades and centuries. And yet, as the Ellesmere Collection attests, the English East India Company—a corporate behemoth so large and powerful that it behaved like a nation-state—found a way to leverage Irish money and Irish servants to achieve its own ambitious imperial agenda.

In some instances, English policies regarding the Irish resonate with the United States’ policies toward Native Americans. The Hastings Collection details, for instance, how English politician Oliver Cromwell systematically removed Catholic Irish children from their parents, communities, and culture, and placed the youngsters in “free schools,” where they were prohibited from practicing their faith, speaking their language, or maintaining their dress. Other Catholic Irish boys were shipped to London to be raised by Protestant English families as “good English men.” The policy of “Anglicizing” native children became synonymous with British empire building in North America, Africa, and Asia well into the 20th century. The impact of these callous initiatives, which the United States and Canada continued toward Indigenous peoples all the way through the 1990s, is still being widely felt.

These sinews, which extend across time and place to bind together our 21st-century present in America and the early modern past in Ireland, underscore the vital importance of history and the inherent value in carefully trawling through archives to piece together a story so that we may better understand ourselves. The Huntington’s rich and vibrant Irish collections provide the materials that make such storytelling possible.

The Kingdome of Irland, from John Speed, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, London, John Sudbury & Georg Humble, 1612. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Funding for this conference has been provided by the Philip V. and Sara Lee Swan Endowment.

Jennifer Wells is assistant professor of history and international affairs at George Washington University.