The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Directory into the Past

Posted on Tue., May 3, 2022 by

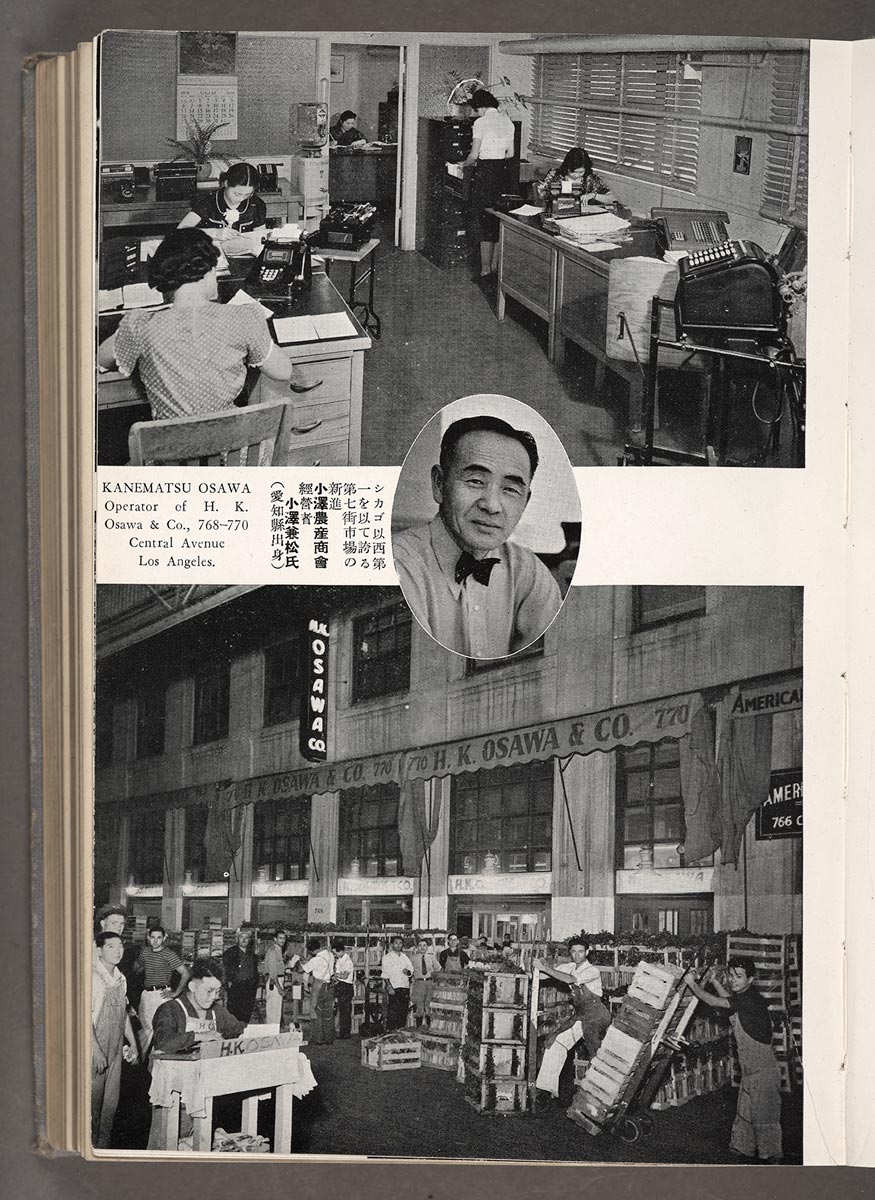

Kanematsu Osawa, operator of H. K. Osawa & Co. in Los Angeles, Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Reconstructing the social and economic lives of Japanese Americans in Los Angeles in the early to mid-20th century requires a great deal of sleuthing in the archives. In The Huntington’s Pacific Rim collections, there are handwritten letters documenting the Japanese American experience in internment camps during World War II, early Los Angeles photographs that reveal the landscape and built environment worked on by Japanese farmers, and oral history recordings that give first-person perspectives on the Japanese American contributions to the flower farming industry in Southern California. Another useful resource is the humble and often-overlooked city directory, which can reveal a great deal about the history of the region and its residents.

Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Over the past few years, The Huntington has acquired several early to mid-20th century annual directories pertaining to Asian American communities on the West Coast of the United States. Combined with The Huntington’s other collections, these materials provide researchers access to names, businesses, addresses, and other useful historical information. The Huntington’s holdings include an 1882 listing of Chinese businesses and several 1930s Chinese telephone directories from the San Francisco Bay Area. Recently, we added a few more rare directories and listings produced during the early to mid-20th century that contain information about Japanese businesses and residents in Los Angeles, Seattle, and Hawai‘i.

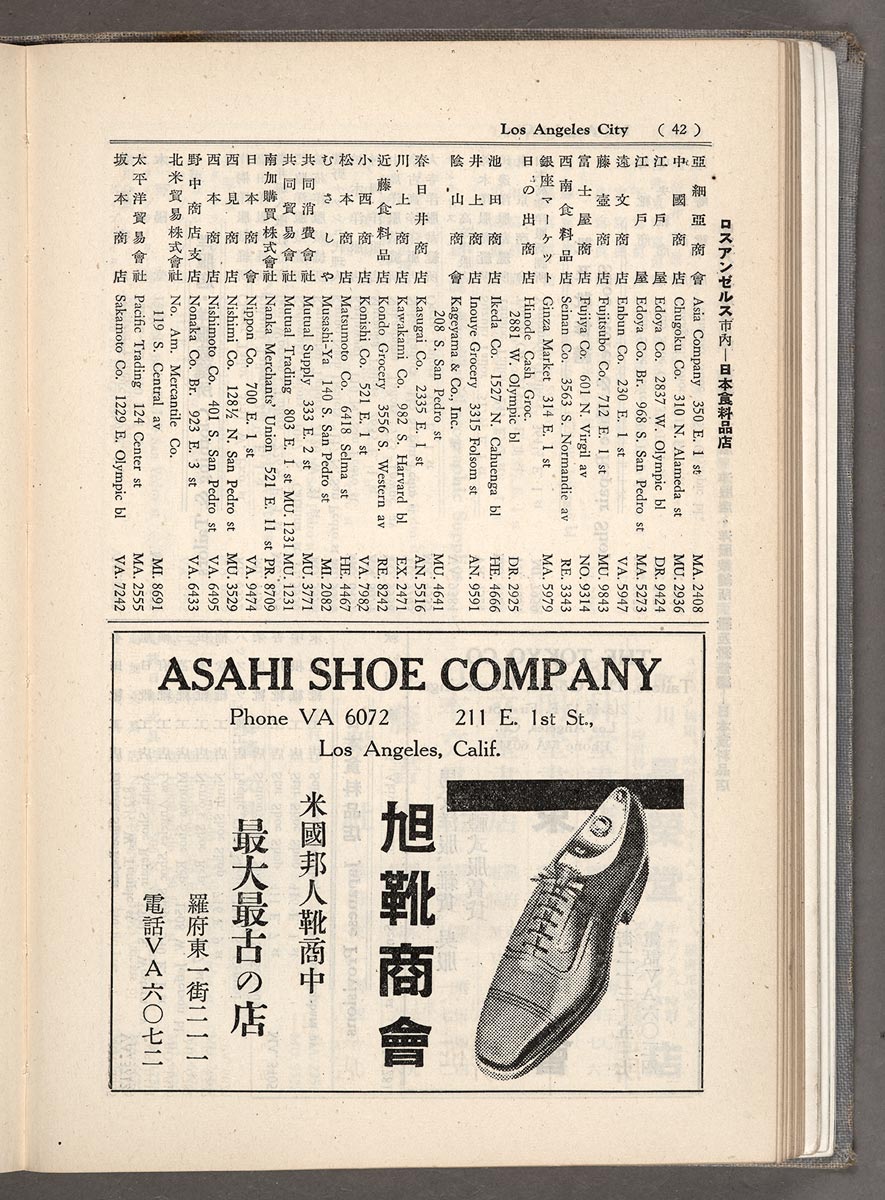

A list of Japanese American businesses in Los Angeles on page 42 of Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

One such recent addition is Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940, published by Rafu Shimpo, a Japanese-English newspaper based in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. The book opens with a few full-page advertisements of Japanese banks and investment firms that showcased their global reach in international finance. It shows various prominent Japanese American organizations, such as the Central Japanese Association of Southern California and the Japanese Hotel Association of Los Angeles, including photos and names of the officers. The 585-page publication also includes statistics on agricultural production, economic analysis, and an index of classified headings of Japanese American–owned businesses and residences in Southern California and elsewhere in the United States and Mexico.

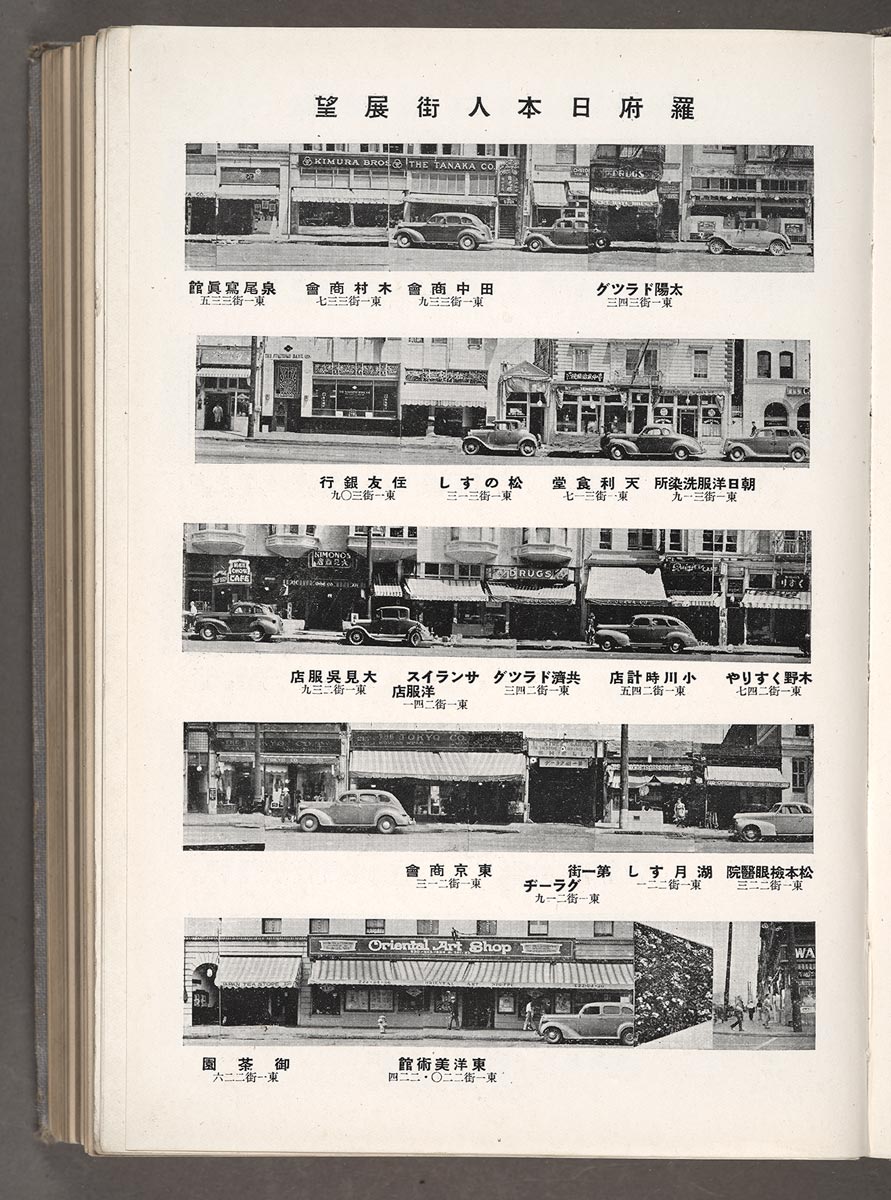

“Views of Japanese Streets in Los Angeles” in Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

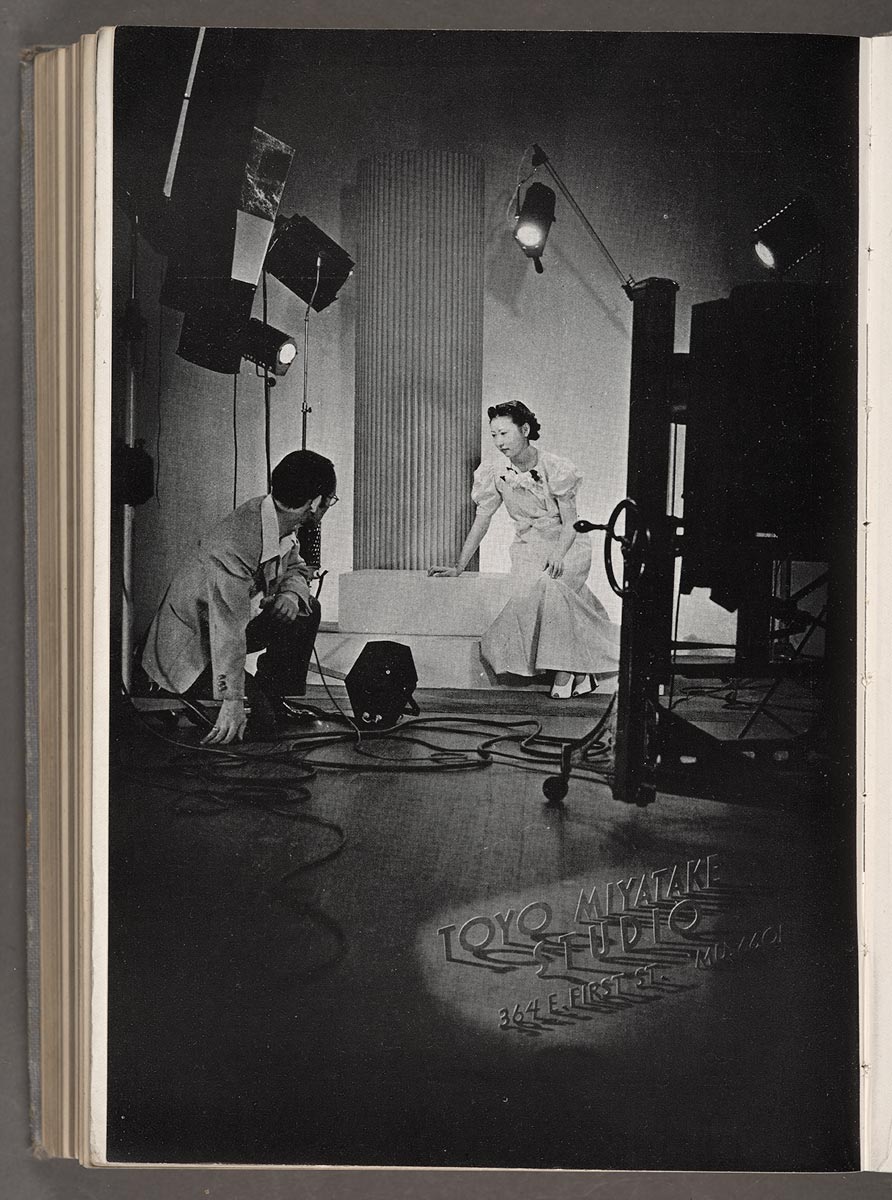

What most caught my attention was the section called “Views of Japanese Streets in Los Angeles.” Predating but akin to Shohachi Kimura’s Ginza kaiwai (1954) and Edward Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), Rafu nenkan offers viewers a continuous panoramic photographic view of streets in Little Tokyo in six full pages. Readers are invited to take imaginary walks down East First and North San Pedro streets in 1939 Little Tokyo. One can browse businesses that are no longer there today, such as Aki Chop House, Toyo Printing Co., and Yokohama Specie Bank. This form of topographical and photographic recording not only captured the business facades and vernacular architecture of an important ethnic district, but also preserved the economic and social vibrancy of Little Tokyo before the 1942 mass incarceration of about 120,000 Japanese Americans in the American West during World War II.

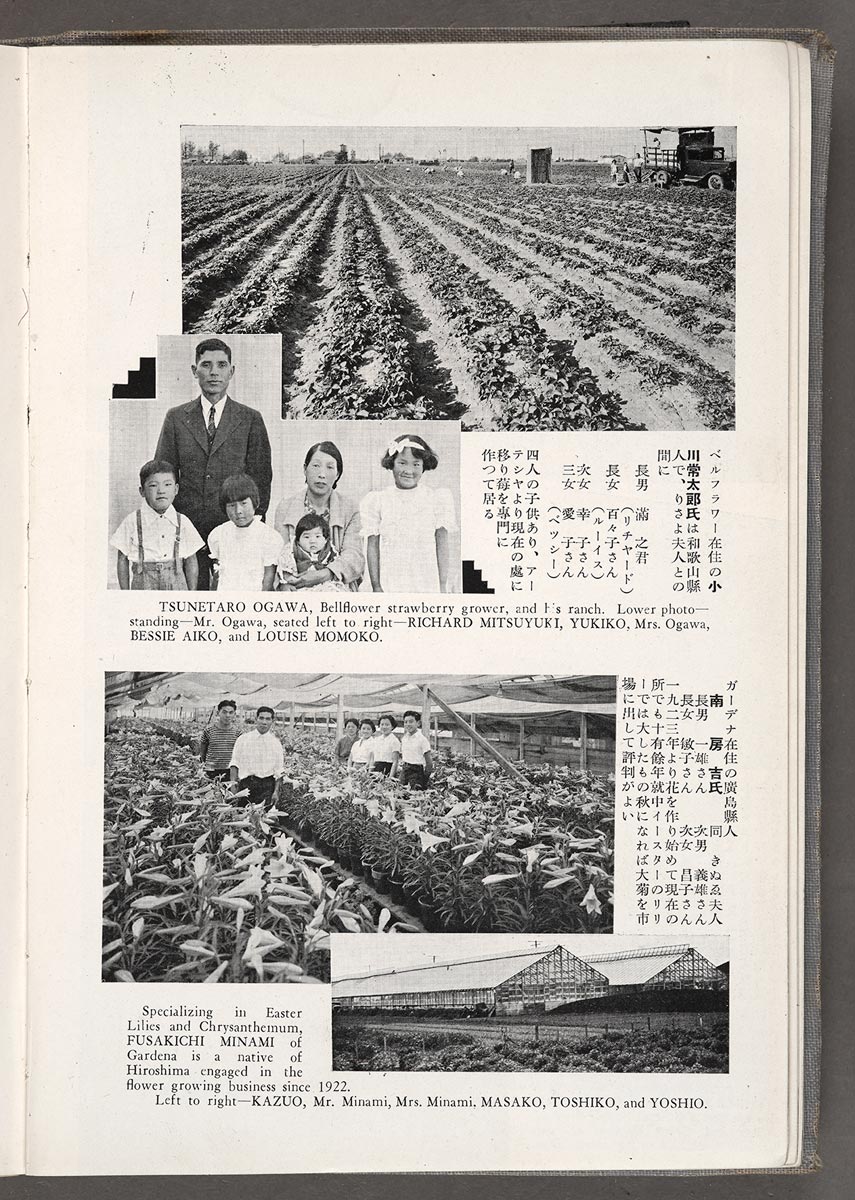

Tsunetaro Ogawa, Bellflower strawberry grower, and Fusakichi Minami, Gardena lily and chrysanthemum grower, Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

City directories such as Rafu nenkan helped preserve the history of a crucial aspect of the larger American economic system: the exchange of money, labor, and other resources within an ethnic economy. Generally speaking, ethnic economies develop in response to demands for specialized goods and services not found in the mainstream marketplace. Language and cultural barriers are another motivator for the formation of ethnic enclaves. Community formation within enclaves affords immigrants access to commercial, employment, and social opportunities that may not be easily found in what may be considered a hostile host society. From 1939 to 1940, Little Tokyo and its surrounding area supported more than 100 categories of businesses, professional services, and social organizations that attracted Japanese and non-Japanese people alike.

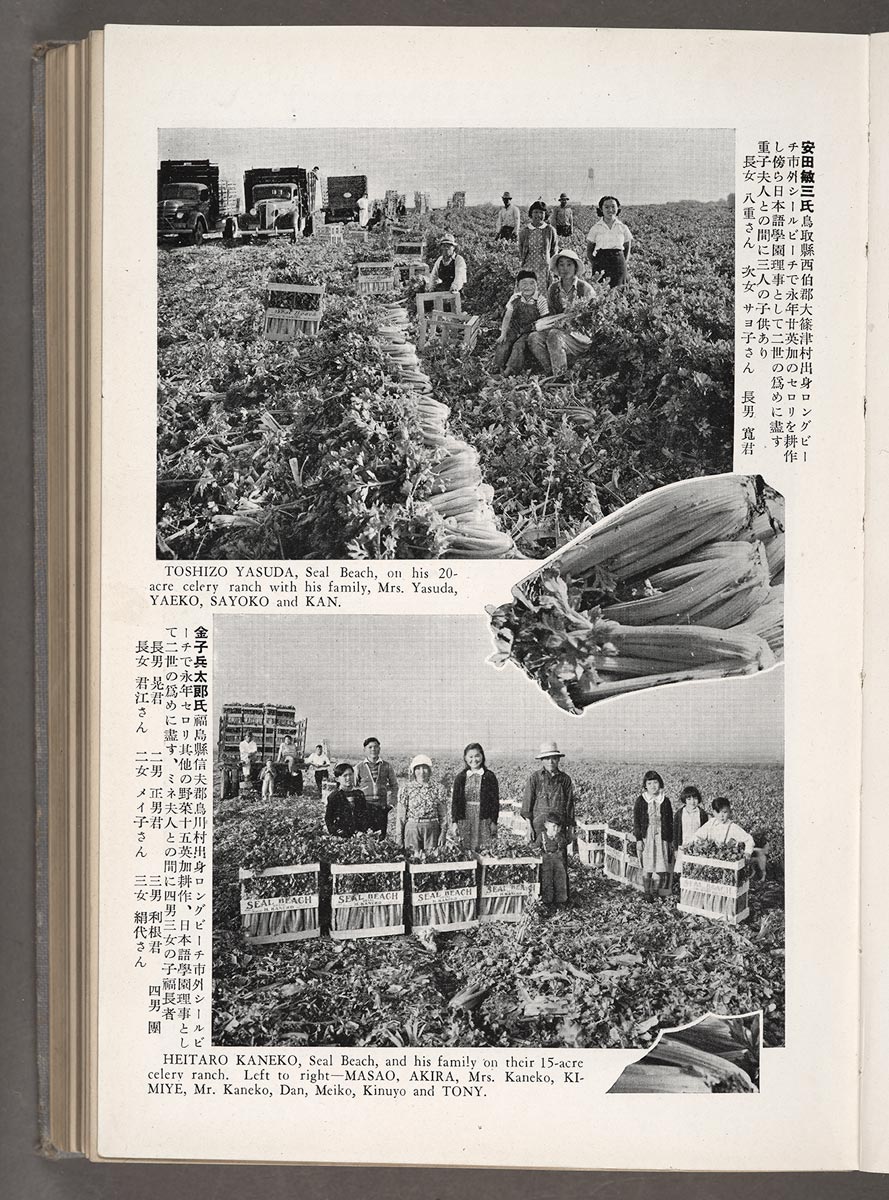

Toshizo Yasuda, Seal Beach celery grower, Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

City and business directories were compiled annually and typically discarded once new editions were published. Today, the few that survive provide incredible insights into the communities they served as well as a large quantity of textual and photographic documentation. Historians rely on directories to reconstruct and interpret the past; genealogists use them to track down family members; and filmmakers depend on city directories to faithfully re-create historical neighborhoods on camera. Over a period of years, decades, and even centuries, directories tie an individual, family, or business to a specific location and time, allowing historians to study growth and decline. Very few publications offer this kind of comprehensiveness, coverage, and consistency in recording information over a long period of time. As a curator, I am always on the lookout for historical city directories that may be sitting forgotten in an attic.

Toyo Miyatake Studio in Los Angeles, Rafu nenkan 羅府年鑑: The Year Book and Directory, 1939–1940. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Li Wei Yang is the curator of Pacific Rim collections at The Huntington.