The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Is Shakespeare Still Relatable?

Posted on Tue., May 10, 2022 by

R. C. de Boer, William Shakespeare, 1892, stone, after a bust cast by Ferdinand Barbedienne. Photo by Don Martirez.

Henry E. Huntington famously built a landmark collection of rare early editions of William Shakespeare’s plays and poems, which remain hugely important to scholars. But what about everyone else? For many, our image of Shakespeare is a cold white marble bust or a dry and dusty textbook from high school days. What, after all, does Shakespeare have to do with us and with some of the biggest and most controversial issues of our time, like the climate crisis, racism, or gender identity? And is Shakespeare relatable to all of us, regardless of our race? Or whether we are gay, straight, or trans? From May 13 to 14, a diverse group of scholars will address these questions at a Huntington conference titled “Shakespeare and the Poetics and Politics of Relevance.”

If such questions seem inappropriate in relation to the Bard, we might consider what Hamlet tells the troupe of actors who visit Elsinore, namely that “the very purpose of playing . . . both at the first and now, was and is to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature . . . and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” In other words, the whole purpose of theater always has been and always will be to reflect on the present. Hamlet is saying that theater is useless if it is not relevant to the present and if it is not relatable. Indeed, what is remarkable about Shakespeare’s works is that, when we read them with our present time in mind, the issues they address become starkly pertinent to our current concerns even as their specific historical manifestations remain distinct. Shipwrecked on the shores of an unnamed island, Antonio in The Tempest, for example, remarks on the “quality of climate,” while Macbeth is preoccupied with “fog and filthy air” as indicators of the way that moral corruption has polluted the political climate.

![William Shakespeare, The tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke. Newly imprinted and inlarged, according to the true and perfect copy lastly printed. London: Printed by W[illiam]. S[tansby], between 1619 and 1623 (?), page 50. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/verso/verso-is-shakespeare-still-relatable-02-25004_huntlib-_shakespeare-annc_r3-1.jpg)

William Shakespeare, The Tragedie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke. Newly imprinted and inlarged, according to the true and perfect copy lastly printed. London: Printed by W[illiam]. S[tansby], between 1619 and 1623 (?), detail of page 50. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

While our own increasingly nonbinary gender culture may seem a bridge too far in terms of any argument for Shakespeare’s current relevance or relatability, in fact that is probably where he is closest to us. Far from being an idea that was alien to Shakespeare, “trans” culture was part of his theater, where male actors performed all the female roles. We cannot put the gender-bending games in comedies such as Twelfth Night and As You Like It down to the practical necessity of having boys play women, however, because the plays’ risqué jokes simply luxuriate in sexual confusion. Surprisingly, Shakespeare more often depicts gender fluidity than the reverse. Indeed, all of Shakespeare’s great tragic heroes are in some way tinged with femininity. For example, macho-man Macbeth, whose brutality on the battlefield is established at the very beginning of the tragedy, is later accused by his wife of succumbing to feminine remorse after he murders the king. She tells him that his fears are like “A woman’s story at a winter’s fire, / Authorized by her grandam.” Similarly, the murdered King in Hamlet was a warrior who continues to wear his armor even as a ghost. In life, he decimated his enemies and “smote the sledded Polacks on the ice.” But, by his own admission, Hamlet bears no resemblance to his father’s epic masculinity. Just like the proverb “men are deeds and women are words,” Hamlet keeps talking—in eight soliloquies—but does not avenge his father’s death until the very end of the play. Instead, he “[M]ust, like a whore, unpack my heart with words” [my emphasis]. Neither is King Lear an exception to this pattern; he describes his emotional agony as “this mother [that] swells up toward my heart.”

Issues of race and racism are also front and center in a number of the plays, most obviously in Othello, in which the ostensibly “begrimed and black” tragic hero is partnered with Desdemona, whose skin is whiter “than snow / And smooth as alabaster”; while the prostitute Bianca, whose name literally means “white,” is shown to be morally stained by her means of livelihood and yet impeccably honest and loyal in her affections. In The Tempest, Caliban is deemed to come from a “vile race,” and yet Shakespeare endows him with the best and most lyrical lines in the play. Meanwhile, in The Merchant of Venice, audiences must decide for themselves whether Antonio’s antisemitic triumph over Shylock annuls the latter’s poignant articulation of his full humanity: “If you prick us, do we not bleed?”

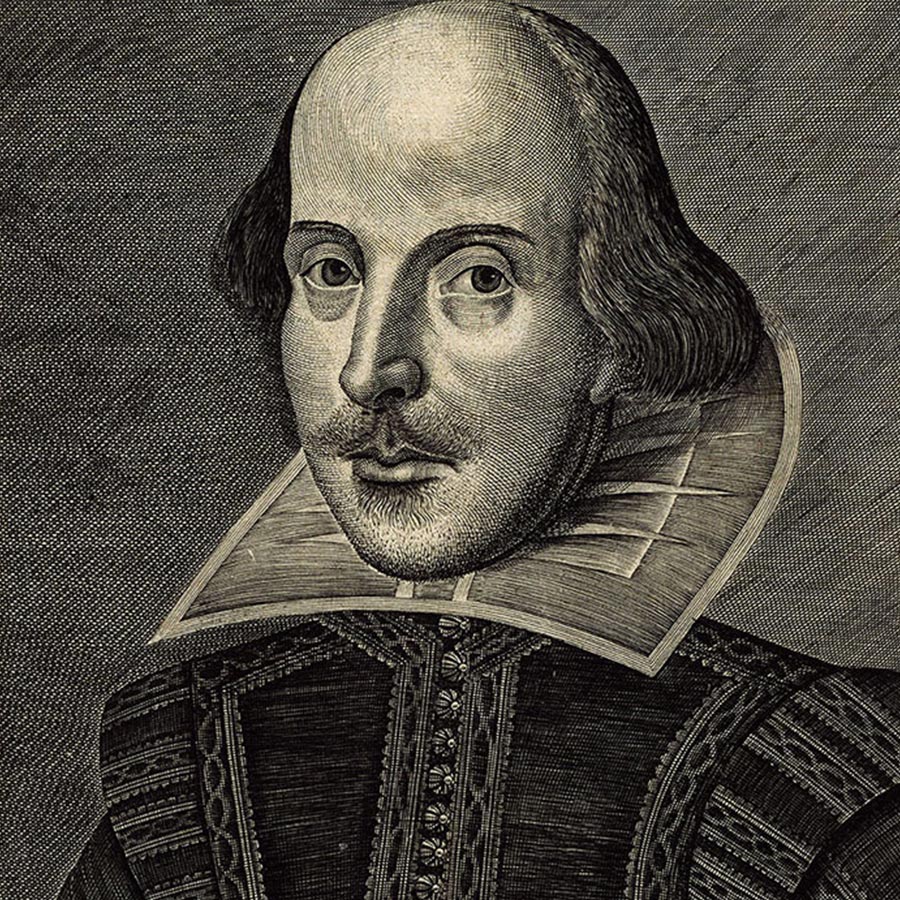

Shakespeare’s image as it appeared on the title page of his Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, known as the First Folio, published in London in 1623. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Indeed, Shakespeare never bangs us over the head with a blunt political agenda. His plays encourage directors to shape productions in ways that they see fit and audiences to respond to what they see on stage. Audiences and readers are entrusted with powers of discernment. We get to decide. Now that’s relatable.

You can register for “Shakespeare and the Poetics and Politics of Relevance” and view the conference schedule online.

Dympna Callaghan is University Professor and William L. Safire Professor of Modern Letters in the Department of English at Syracuse University.