The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

#5WomenArtists in the American Collections

Posted on Wed., March 8, 2017 by

Detail of Harriet Goodhue Hosmer's Zenobia in Chains, 1859, marble. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

The history of art is peppered with tales of women artists who struggled to gain the same recognition as men.

To shine a light on women’s artistic bounty, the National Museum of Women in the Arts kicked off a social media campaign last March to honor Women’s History Month. They asked, “Can you name five women artists?” More than 400 art museums and 11,000 individuals participated, tagging their posts with #5WomenArtists.

The campaign is back this year. We decided to peruse the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art for five of our favorite works by women artists. You can find all five on view now. (And, if you want to join the conversation on Twitter and Instagram, use the hashtag #5WomenArtists.)

1. Alma Woodsey Thomas (1891–1978), Leaves Fluttering in the Breeze, 1973

The visual impact of Alma Woodsey Thomas's Leaves Fluttering in the Breeze, 1973, acrylic on canvas, has withstood the test of time. Interest in the artist experienced a renaissance last year, with several exhibitions of her work on view. On loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photo by Kate Lain.

Expressionist painter Alma Thomas was the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972 and the first to have one of her artworks enter the permanent collection of the White House (Michelle Obama installed Thomas’s Resurrection in the family dining room).

Leaves Fluttering in the Breeze shows her signature flair for brilliantly hued abstract compositions, a style associated with the Washington Color School. Thomas was born in Columbus, Georgia, and raised in Washington, D.C. She earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from Howard University and a master’s degree in art education from Columbia University. Thomas’s early work was representational. After retiring as a Washington, D.C., public school art teacher, she devoted herself full time to her art and made the shift to abstract expressionism.

2. Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830–1908), Zenobia in Chains, 1859

At first, critics didn’t believe that Harriet Goodhue Hosmer’s Zenobia in Chains, 1859, could be the work of a woman. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen.

Hosmer’s larger-than-life marble sculpture of Zenobia, the 3rd-century queen of Palmyra (a site near present day Syria) made a splash when it was exhibited at the Great London Exposition in 1862. Such fine sculpting—visible in the queen’s regal bearing, her elaborate court dress, and her leg pressing against her robe—must have been the work of a man, deduced critics. Several male sculptors who had worked with Hosmer in Rome came to her defense, convincing skeptics that the monumental work was indeed her creation.

3. Agnes Pelton (1886–1961), Passion Flower, ca. 1945

Agnes Pelton, Passion Flower, ca. 1945, oil on canvas. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Pelton was born in Germany to American parents. She spent her early career in New York, where she studied with Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922), who counted Georgia O’Keeffe among his students. Later, Pelton moved to the desert enclave of Cathedral City, California, where her paintings took on a mystical serenity. The radiance of Passion Flower imbues the simple image of a flower with something more visionary—reflecting her participation in the Transcendental Painting Group and the influence of movements such as Theosophy, Zen Buddhism, and other forms of non-Western thought.

4. Helen Lundeberg (1908–1999), Irises (The Sentinels), 1936

Helen Lundeberg, Irises (The Sentinels), 1936, oil on canvas. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Lundeberg was born in Chicago and raised in Pasadena. The mountain range in Irises may suggest the area around Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco. Two tall, bearded irises tower in scale against the mountains in the distance. Their positions and stature suggest their role as sentinels over the empty desert landscape.

The dreamlike nature of the plants in the arid environment suggests the influence of Georgia O’Keeffe. Lundeberg was interested in the flower as a symbol of life and death. The work’s title may refer to the Greek goddess Iris, who, along with Hermes, was a messenger to the gods, acting as a link between heaven and earth.

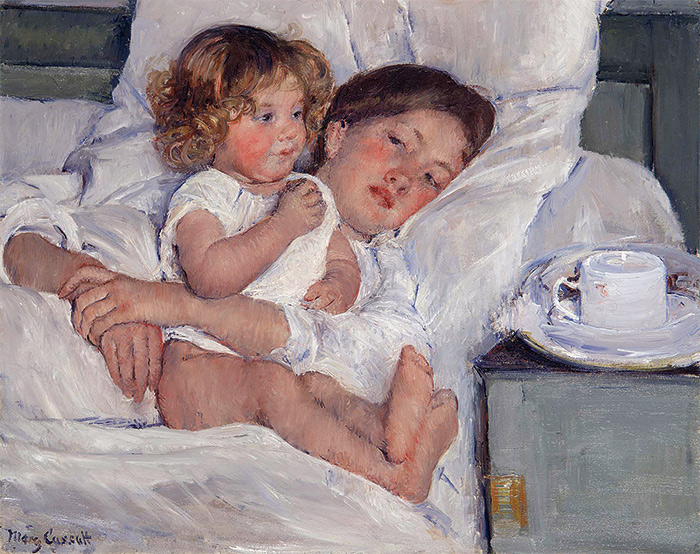

5. Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), Breakfast in Bed, 1897

Mary Cassatt, Breakfast in Bed, 1897, oil on canvas. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Cassatt was one of the first American women to achieve international recognition as an artist. Born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, she spent most of her life in France, where she befriended the French Impressionists, who were using small brushstrokes of unmixed colors to capture the immediate visual impression of a scene. Breakfast in Bed explores a favorite subject of Cassatt’s: the tension between a mother’s focused attention on her child and the child’s desire to explore the world around her. In Breakfast in Bed, the mother gazes at the child wrapped in her arms while the child looks out into the room.

It’s a perfect time to honor the contributions of women artists. Why not take a stroll through The Huntington’s American art galleries?

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.