Posted on Tue., April 7, 2015 by

Side-handled teapots used in China for the sencha tea ceremony became popular in Japan. This earthenware teapot (ca. 1860) from The Huntington’s collection was made by Japanese Buddhist nun Ōtagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875), a renowned poet, painter, calligrapher, and potter.

People who appreciate green tea for its antioxidant properties don’t know the half of it. In a recent Huntington lecture, “Searching for the Spirit of the Sages: The Japanese Tea Ceremony for Sencha” (which you can listen to on iTunes U), scholar Patricia J. Graham shared a poem by Tang dynasty poet Lu Tong that rhapsodizes about the beneficial effects of successive bowls of tea.

“ . . . With bowl number six, I commune with immortal spirits.Bowl number seven, I can barely get down. I only feel pure wind blowing, swishing beneath my arms . . .”

Among China’s intellectual elite, ever since the 8th century, tea possessed an exalted status as a beverage that facilitated spiritual enlightenment. In particular, the sencha form of green tea, made from whole leaves steeped in boiling water, was the tea of choice for Chinese literati. Sencha eventually made its way to Japan, though its road to popularity wasn’t an easy one. According to Graham, political turmoil between the two countries discouraged the Japanese from learning about Chinese culture, including how they prepared tea.

Both sencha (above) and powdered matcha tea come from the same tea plant, Camellia senensis.

At the time, a highly ritualistic chanoyu tea ceremony using another form of tea—powdered green matcha tea—reigned supreme in Japan, especially among the military elite. Exposure to sencha began in the 1600s, through the monks of the Obaku school of Zen Buddhism. Those who disliked the shogun rulers identified with the Obaku monks and their simpler sencha ceremony.

Sencha’s popularity was solidified in the 1700s, thanks to an eccentric, charismatic former monk named Baisao. Known as “the old tea seller,” Baisao peddled sencha on the streets of Kyoto as a way to attain spiritual enlightenment. Baisao called sencha an “elixir to change your very marrow,” urging people to drink the tea because “who knows, you may reach sagehood yourselves.”

Baisao did more than just convince people to drink sencha. His choice of more modest utensils for preparing tea permeated popular culture. When he died, his followers decided that proper sencha utensils should look like his, not the rare and expensive ones used for chanoyu. Chief among these was the unglazed, side-handled teakettle. Items associated with sencha gave rise to an entire craft industry in Japan.

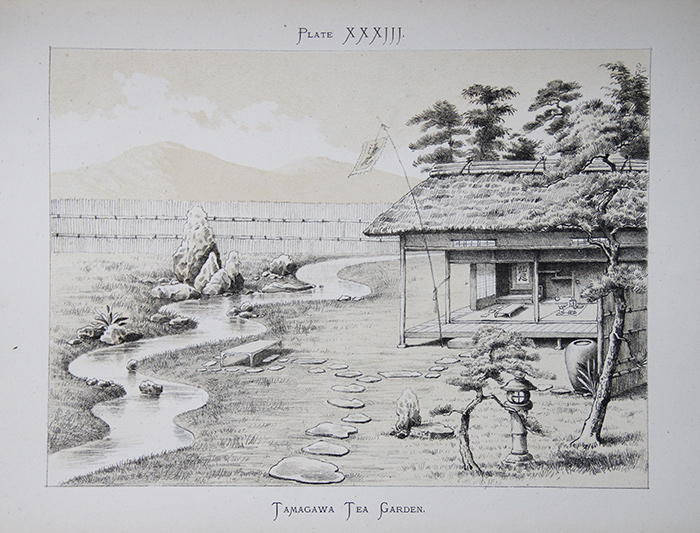

A drawing of the Tamagawa (Jade Stream) Tea Garden, a sencha teamaster’s garden, from Landscape Gardening in Japan, 1893, by Josiah Conder (1852–1920). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The shift to sencha got another boost in 1802 with the publication of a guide in Japanese on how to prepare this form of tea. In the same period, tea ceremonies held by the intellectual class started featuring Chinese art objects—bronzes, cabinets, fans, paintings, scrolls, and baskets with flower arrangements—further encouraging an acceptance of Chinese customs. By the early 1800s, sencha had eclipsed chanoyu in popularity, and with it came a heightened appreciation of Chinese culture.

When asked by an audience member about the caffeine level of sencha, Graham recounted that while studying in Japan, she was drinking tea all day and had trouble sleeping. “Really good green tea makes you feel really alert,” she said.

She quoted Japanese author Natsume Soseki, who in her novel The Three-Cornered Roomwrote: “. . . I would say that it is better to go without sleep than without tea.”

This botanical print of tea appears as the frontispiece for The Natural History of the Tea-tree, 1799, by John Coakley Lettsom, M.D. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can appreciate the practice of the more formal chanoyu ceremony by taking a tour of The Huntington’s Japanese ceremonial teahouse—Seifu-an (the Arbor of Pure Breeze). Informal, docent-led tours are offered between 12:30 and 4 p.m. on the second Monday of each month.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles–based communications consultant.