The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Art and the Garden Movement

Posted on Wed., Feb. 3, 2016 by

Charles Courtney Curran (1861–1942), A Breezy Day, 1887, oil on canvas, 11 15/16 x 20 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Henry D. Gilpin Fund.

The relationship between garden design and painting is the subject of “The Artist’s Garden: American Impressionism and the Garden Movement, 1887–1920,” on view Jan. 23–May 9 in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery. It explores the connections between the American Impressionist movement and the emergence of gardening as a middle-class leisure pursuit.

Featured in the exhibition is a selection of 17 handpicked paintings from an exhibition that originated at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The Huntington’s show includes examples from such noted American Impressionist painters as Philip Leslie Hale (1865–1931), Childe Hassam (1859–1935), and Anna Lea Merritt (1844–1930).

Anna Lea Merritt (1844–1930), Piping Shepherd, 1896, oil on wood, 26 1/8 x 21 5/8 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Henry D. Gilpin Fund.

Beautiful to look at, these paintings also reflect aspects of American life in the late 19th and early 20th century. Industrialization gave parts of the population more free time for gardening in new suburban backyards, and railroads allowed daytrips to the countryside—offering some city dwellers a taste of nature.

American artists were also contributing to the garden movement by depicting the results of this new hobby in their works on paper, canvas, and glass. In her introduction to the exhibition’s catalog, Anna O. Marley, curator of Historical American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, explains that the increasing professionalization of art-making meant that artists, too, had become members of the middle class.

Childe Hassam (1859–1935), The Hovel and the Skyscraper, 1904, oil on canvas, 34 3/4 x 31 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, The Vivian O. and Meyer P. Potamkin Collection, bequest of Vivian O. Potamkin.

“Many of these artists had traveled to Europe, especially France,” says Marley, “where they were exposed to the modernist style of Impressionism. Lingering in the French countryside and in the public parks of Paris, they experimented with impressionist principles of plein-air painting, the study of light, with direct, unmediated compositions, and the application of unmodulated color in quick brushstrokes.”

“The Artist’s Garden” presents an American take on Impressionism. The works are largely domestic pictures about yards, parks, and gardens, or even the middle of the city, such as Childe Hassam’s The Hovel and the Skyscraper, in which construction starts to obscure the artist’s view of Central Park. The painting shows a contrast between two seemingly opposing elements—the “slow cadence of the snow-covered park” and the “frantic Manhattan real estate market,” says James Glisson, The Huntington’s Bradford and Christine Mishler Assistant Curator of American Art.

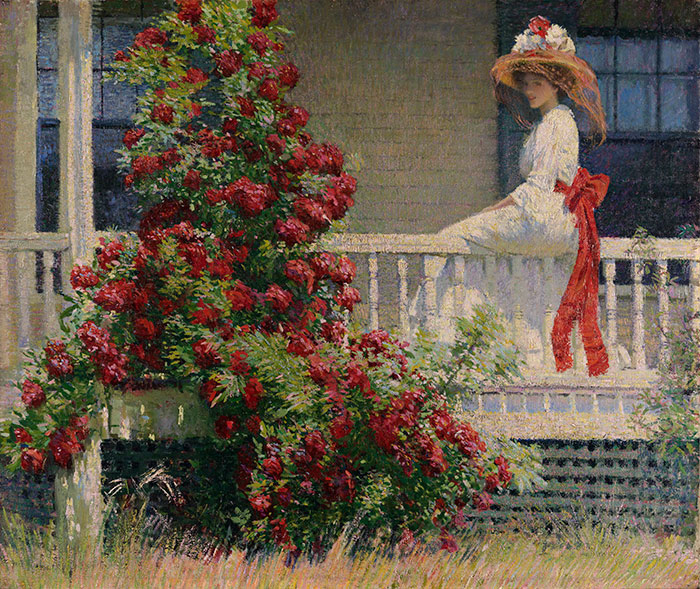

Philip Leslie Hale (1865–1931), The Crimson Rambler, ca. 1908, oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 30 3/16 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Joseph E. Temple Fund.

The very plants and flowers that appear in the paintings are also telling. Garden hobbyists were seeking out seeds, tools, and fertilizer for their new suburban backyards, and new hybridizing techniques were creating ever larger and brighter flowers and bigger and more colorful fruits and vegetables.

At first glance, for instance, Phillip Leslie Hale’s The Crimson Rambler(ca. 1908) looks like a simple scene of summer, portraying an elegant young woman seated next to a cascade of blooming roses. Seen through the lens of the period, the painting takes on greater meaning. The ‘Crimson Rambler’ was a recently hybridized rose variety that had become wildly popular. To many viewers at the time, the appearance of this trendy hybrid marked the painting as contemporary and sophisticated.

"The Artist’s Garden" will likely appeal to both artists and gardeners. It may also pique the curiosity of social historians, who might gaze at these magnificent gardens and detect a range of clues that tell the story of how some Americans lived a century ago.

Henry Asbury Rand (1886–1961), Snow Shadows, 1914, oil on canvas. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, John Lambert Fund.

Over the span of the exhibition, a newly installed garden outside of the gallery will take shape. The plants were chosen to evoke the classic gardens of the era as painted by the American Impressionists and will feature delphinium, foxglove, snapdragon, and sweet pea, as well as later appearances by poppies and red flax.

The exhibition catalog, The Artist's Garden: American Impressionism and the Garden Movement, is available from the Huntington Store.

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.