The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Artist Mario Ybarra Jr.

Posted on Wed., Aug. 15, 2018 by

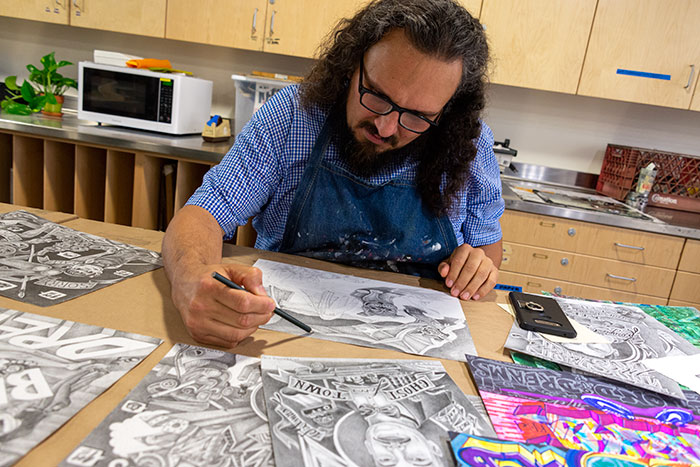

Artist Mario Ybarra Jr. at work. Photo by Kate Lain.

In March 2018, The Huntington announced that it was partnering with East Los Angeles College’s Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) for the third year of The Huntington’s /five initiative, inviting noted Los Angeles artists Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. to create new work in response to The Huntington’s collections around the theme of Identity. The project will culminate in an exhibition that will be on view at The Huntington from Nov. 10, 2018 to Feb. 25, 2019. Carribean Fragoza, a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California, focuses in this post on Mario Ybarra Jr.

The summer day simmered. As artist Mario Ybarra Jr., his assistant Jennifer Vanegas, and I strolled through the gardens under the shade of carefully trimmed foliage, steam rose from the warm, dark earth underfoot. Sweat beaded on our faces and dampened our shirts as we walked along the well-demarcated paths, but then more briskly through the rougher back trails usually used by groundskeepers. Finally, we arrived at the Chinese Garden. Almost in unison, we slumped on a shaded bench overlooking a koi-filled pond like a trio of wilting flowers laid out to dry—an artist, his assistant, and a writer.

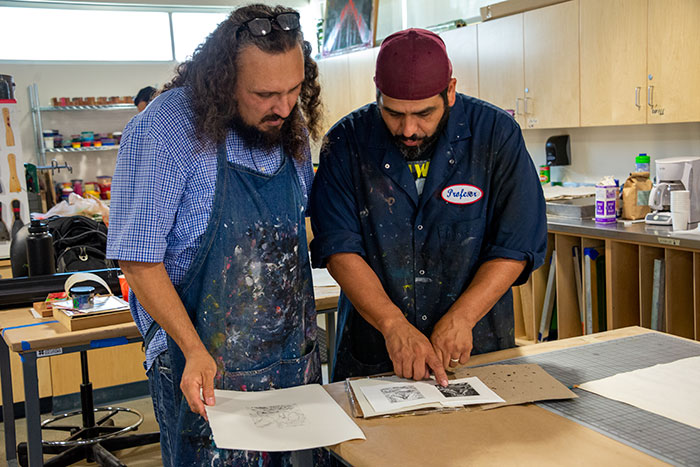

Ybarra (left) and Sergio Teran (right) in Teran’s print studio at Cerritos College. Photo by Kate Lain.

Despite our look of repose, or perhaps exhaustion, our true work was about to begin.

Ybarra began by acknowledging the moment. “We’re not the guy planting the trees—the brown person you’re most likely to see in places like this. But we’re cultural workers, and right now, it’s our job to sit under the trees and think deeply. That’s work, too.”

Indeed, Ybarra has been thinking extensively about the meaning of work, particularly in arts professions and for people of color. For this year’s /five residency, Ybarra and Carolina Caycedo have been taking a careful look at the labor, mainly by people of color, that built Los Angeles and the American West. The economies of culture in the arts world and the film and TV industries have played essential roles in the shaping of Greater Los Angeles, as have narratives about places and people. Hollywood, for example, has tirelessly reinforced racial stereotypes, casting Latinos primarily as maids, gardeners, and criminals. But Ybarra is looking to push beyond these limited perspectives that insist on seeing brown and black bodies almost exclusively as sources of labor rather than as intellectual or cultural producers.

Ybarra holds a printing plate etched with his self-portrait. It was inspired by small, intimate works by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and a portrait of Dürer himself by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677) that Ybarra viewed at The Huntington. Photo by Kate Lain.

“I’m not trying to put manual labor and my labor into any kind of hierarchy. But I also don’t want to romanticize the blue collar [class], which is where I came from,” says Ybarra, whose relatives worked as longshoremen along the San Pedro and Long Beach ports near his hometown, Wilmington.

While exploring the gardens and the Library collections at The Huntington during the past few months of his residency, Ybarra has considered ancient philosophers and artists—Greek, Roman, and Chinese—and their foundational contributions to Western or Eastern thought. “Where do you think they did all of their deep thinking? Probably while strolling around beautiful gardens like this one. And that’s what we’re doing,” he says.

Ybarra inks a printing plate etched with his self-portrait. Photo by Kate Lain.

As Ybarra revisits the ancients, he is thinking about how he might reinterpret or reappropriate some of those ideas or traditions to reflect his own experience as a Chicano in Greater Los Angeles. Of all the items in The Huntington’s collections of garden plants, books and manuscripts, and works of art, it was small-scale works by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)—and a portrait of Dürer himself by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677)—that captivated Ybarra’s attention and stimulated his imagination the most. He was fascinated by how works so small and personal could be so enduring after many centuries and still speak clearly to a viewer today.

“In contemporary art, you see a Chris Burden piece, or a Richard Serra, and they are monumental in size. They take an entire workforce to operate. Dürer’s works are small and intimate. They create a personal headspace for an exhibition. The work can have longevity, meaning, and poetry even if it’s intimate.”

Ybarra adjusts the printer. Photo by Kate Lain.

Ybarra’s turn to traditional forms of art is in sync with his recent return to the humble yet foundational art of drawing by hand (rather than producing gallery-scale installations). The process of drawing has been a way for Ybarra to reflect himself back into The Huntington’s collections. “Drawings are self-reflective. Drawing is also a way of citing the self.”

Ybarra is applying his drawing skills to another process that is entirely new to him—the creation of a series of aquatint etchings. He describes the meticulous and extensive labor of creating the etching wherein the hand drawing is only the initial point of departure. During the course of the summer, he has joined artist and professor Sergio Teran in his print studio at Cerritos College, where, under Teran’s guidance, he has learned the centuries-old process of printmaking. “The movements and gestures are in some ways ritualistic. I’m still learning what they are,” he notes.

Ybarra holds a print of his self-portrait. Photo by Kate Lain.

Select prints, as well as Ybarra’s drawings, will be on view in a November exhibition at The Huntington, alongside work by fellow /five resident artist, Carolina Caycedo.

Carribean Fragoza is a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California.